|

|

|

|

In this project, I implemented a cloth simulator starting from the data structure for the cloth all the way up to collisions. I kept track of the points of the cloth on a grid of point masses, and applied different forces to determine the direction and next position of each point mass. With these point masses, I was also able to calculate collisions between the cloth and objects, specifically spheres, planes, and the cloth itself (using an efficient hashing technique). I also learned how to manipulate the cloth with various attributes (density, spring constant, damping) to change the cloth's apparent weight, stiffness, and other stuff as well. I ran into many debugging struggles, including segmentation faults and malloc errors, and this project really made me dive deep into the spec and fully understand the processes for the tasks I implemented. With this project, I am now given the opportunity to boast to my peers about having implemented a cloth simulator.

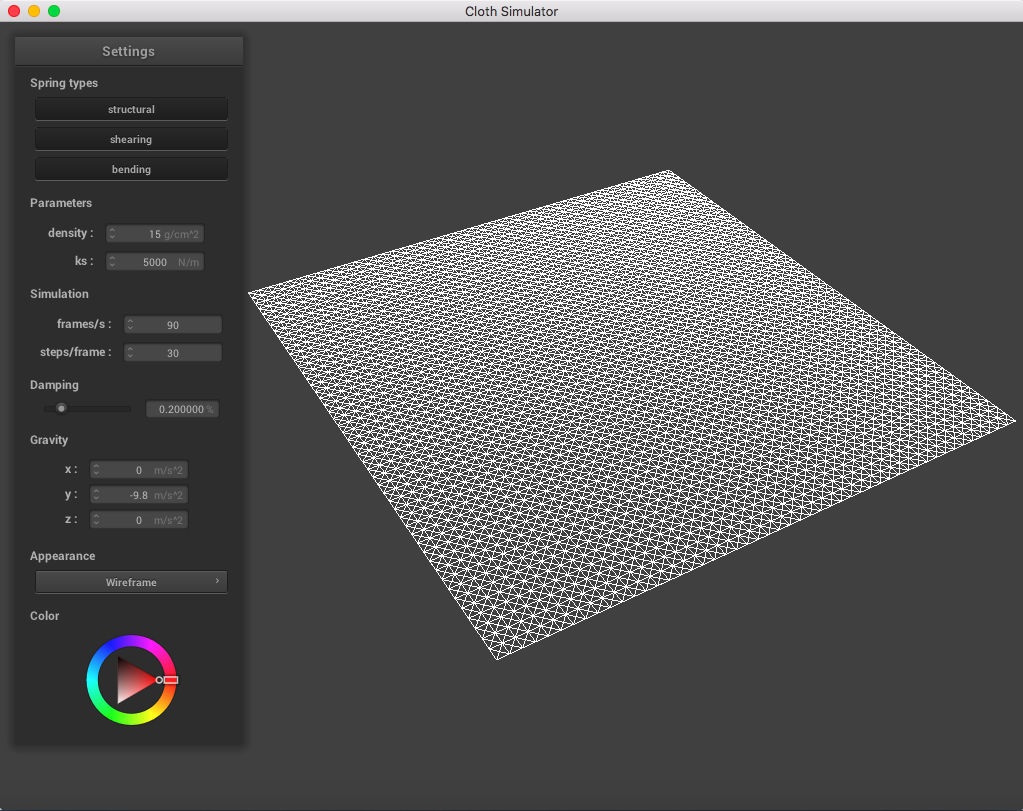

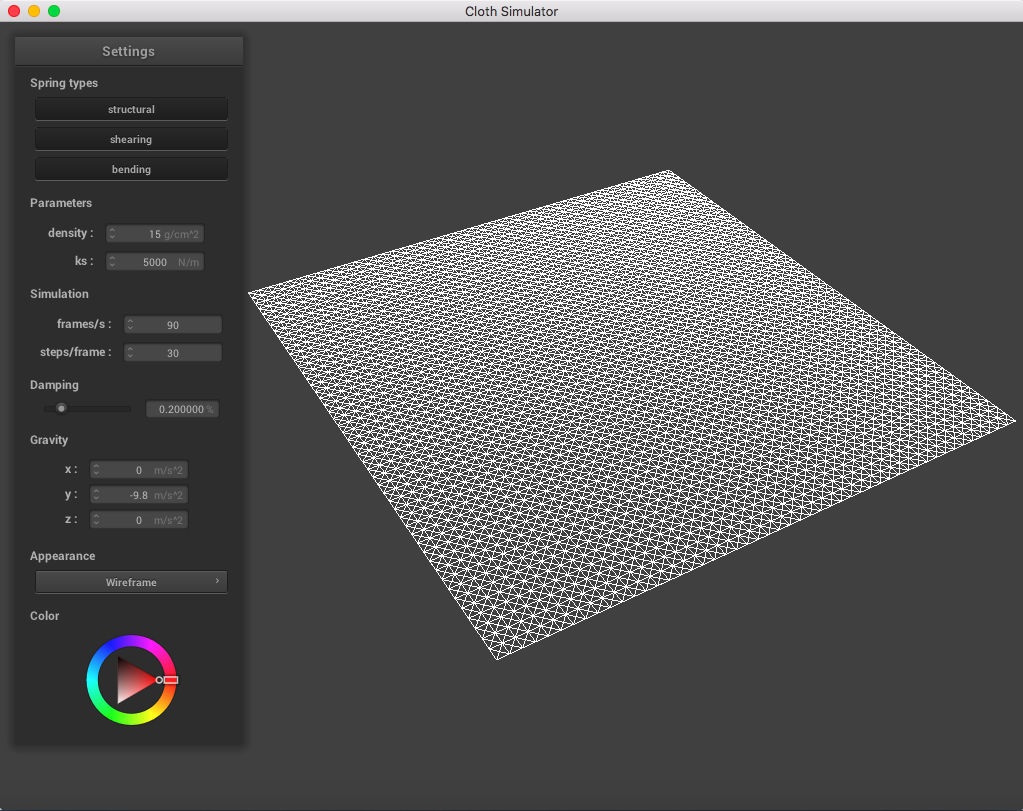

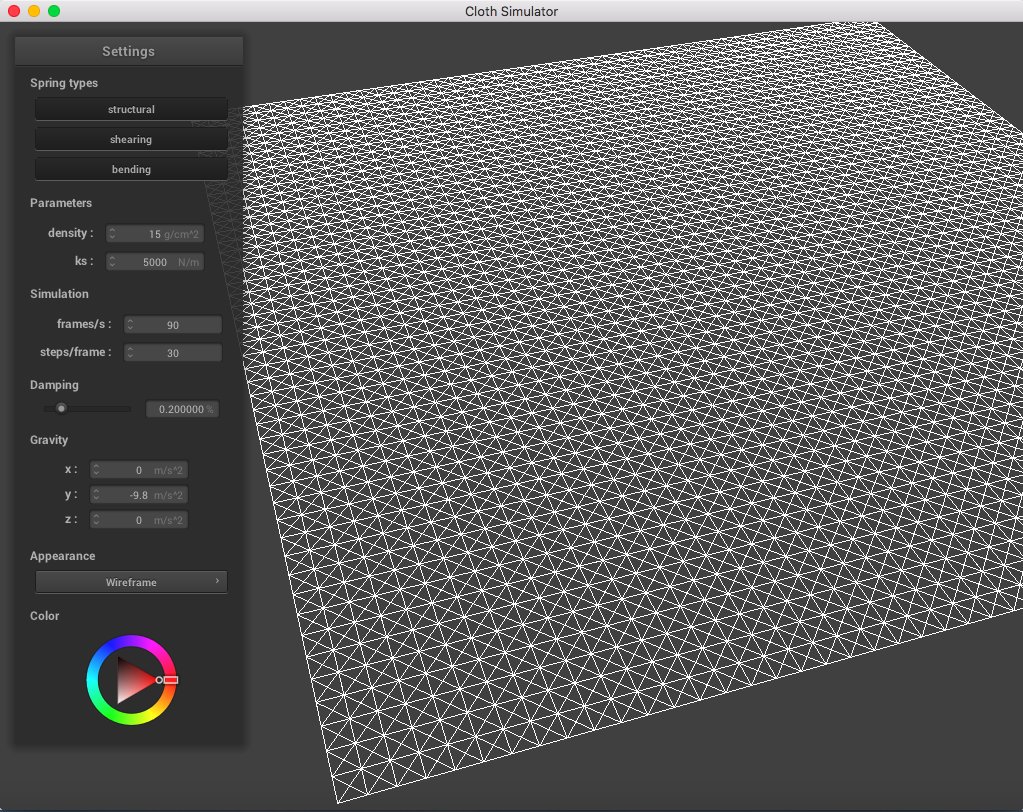

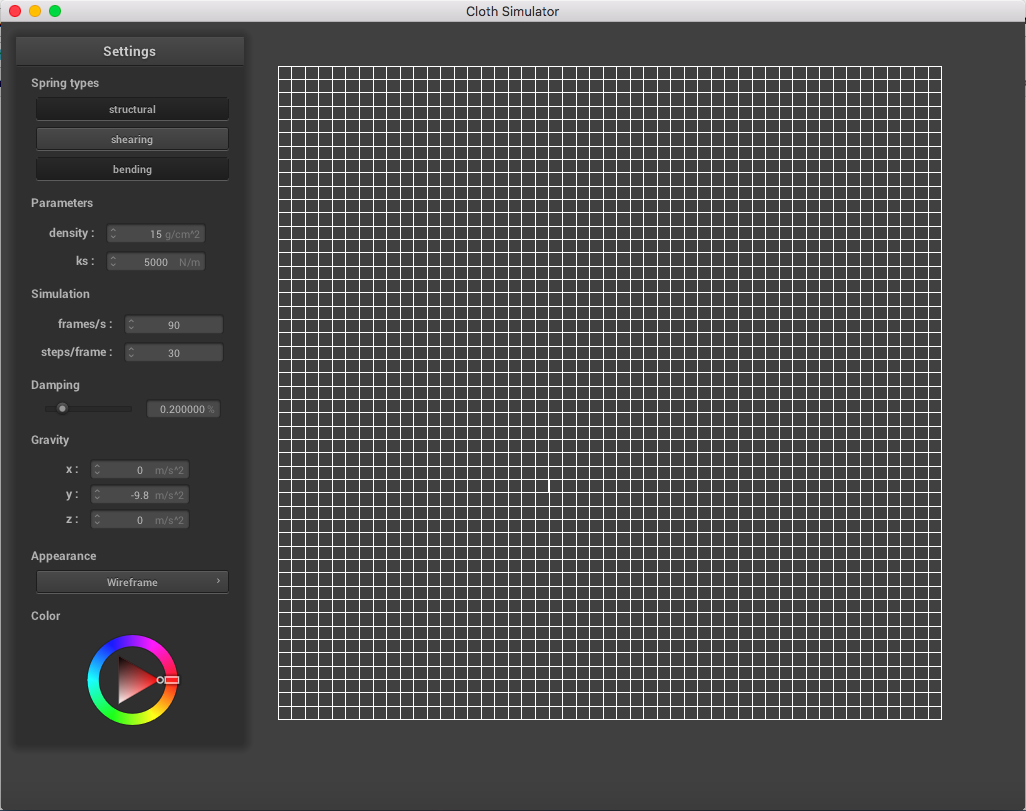

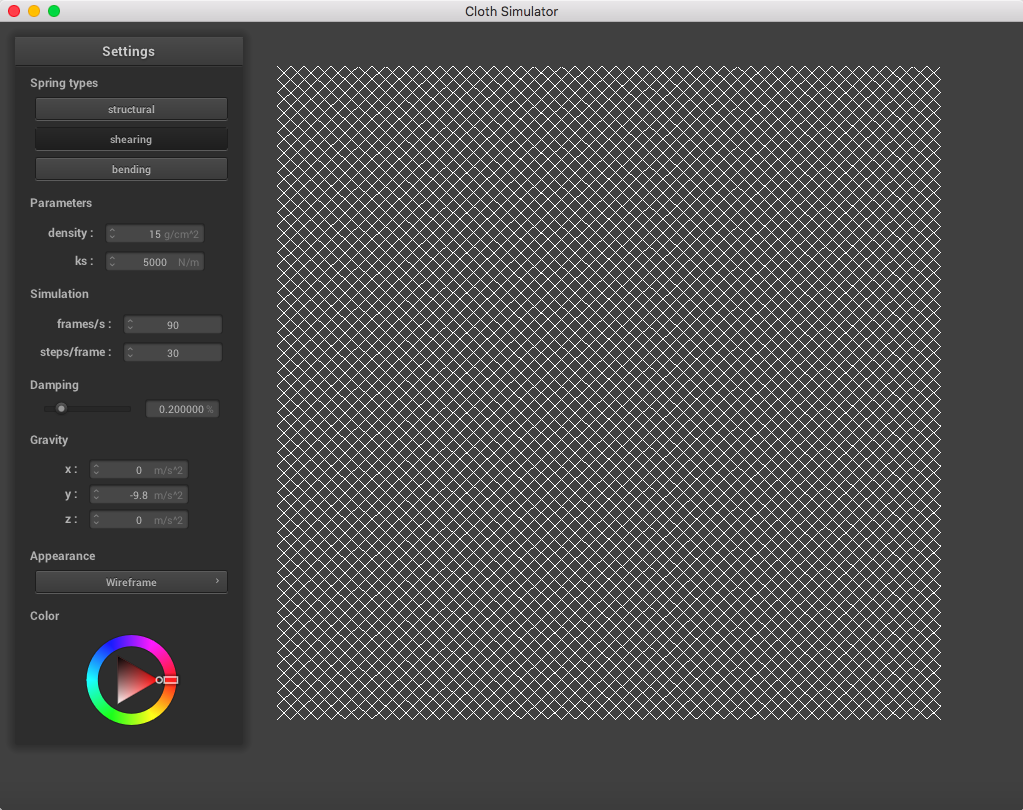

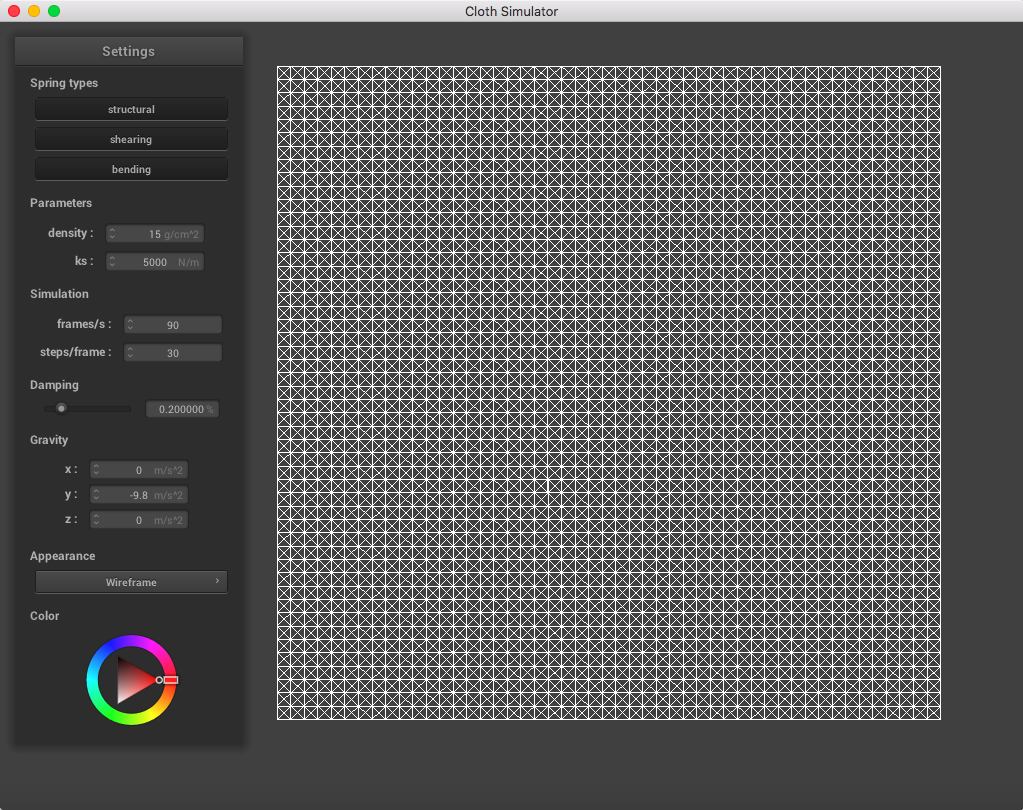

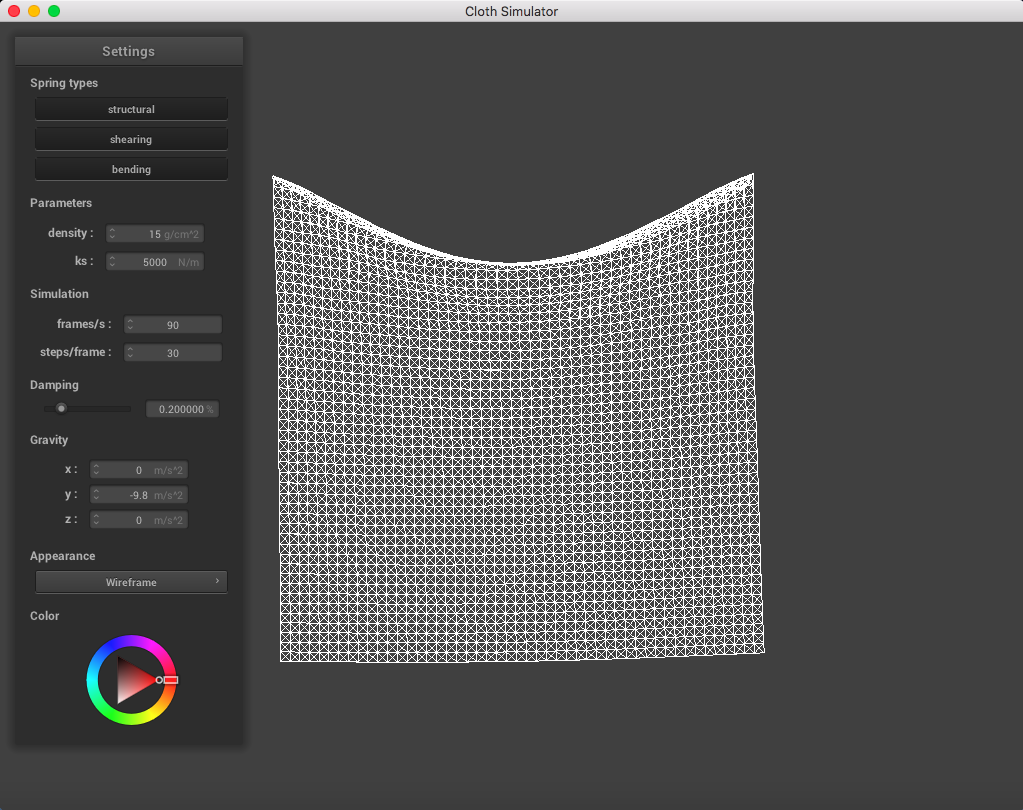

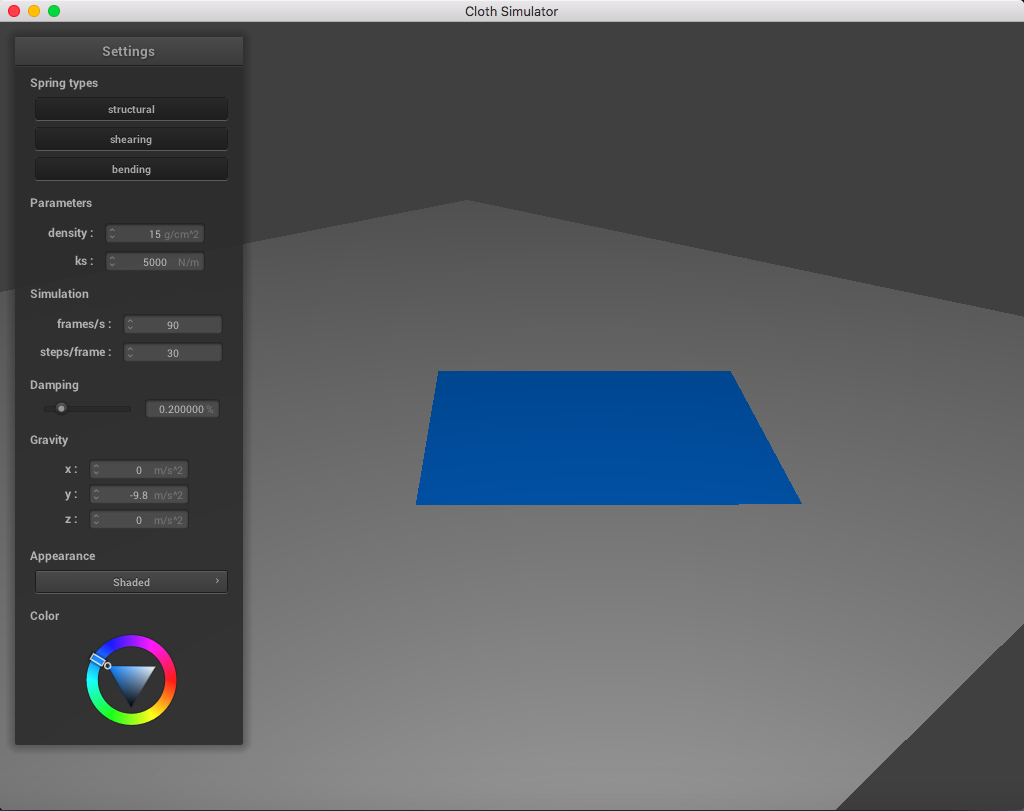

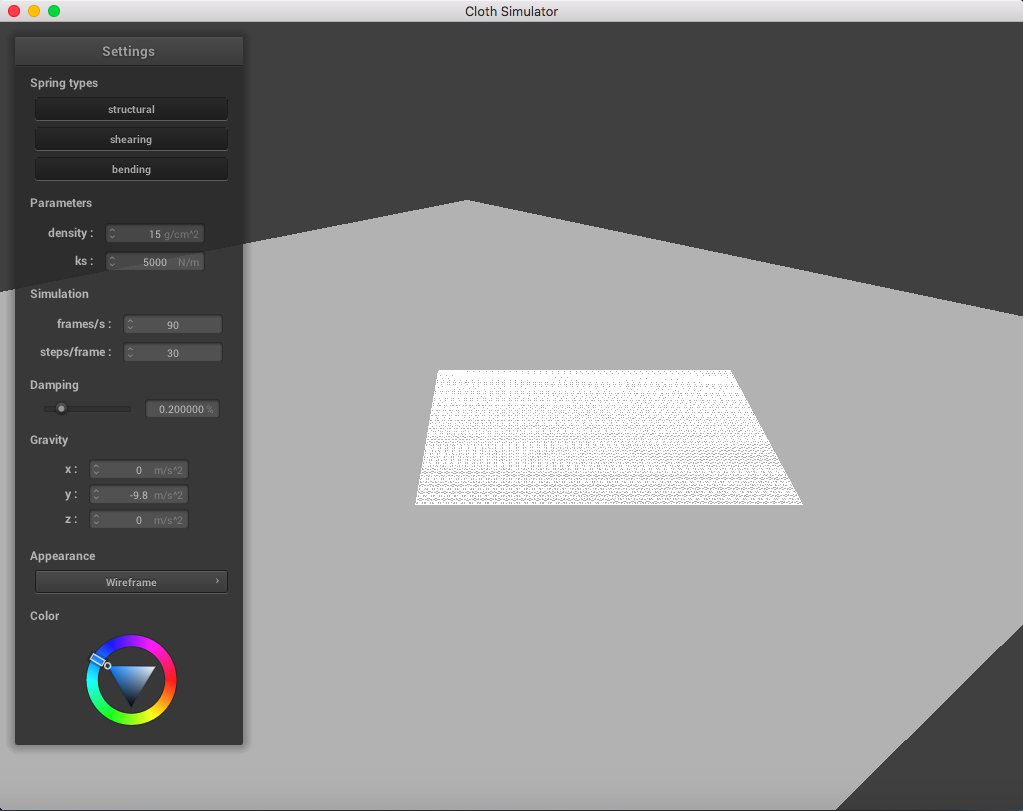

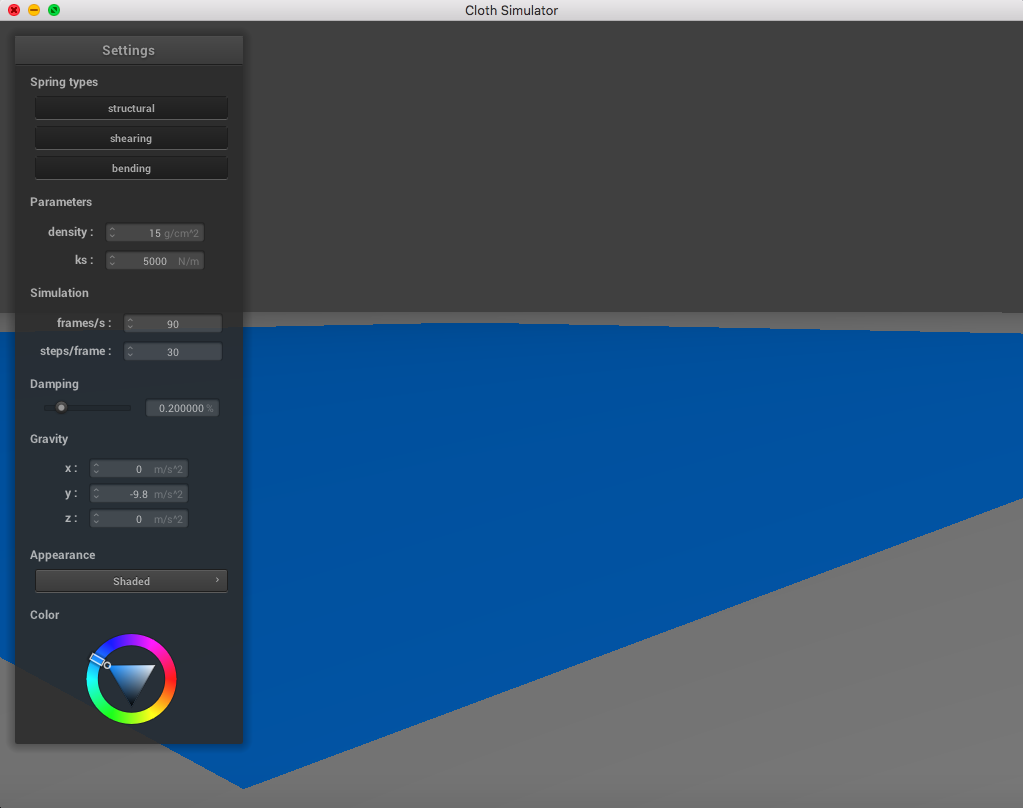

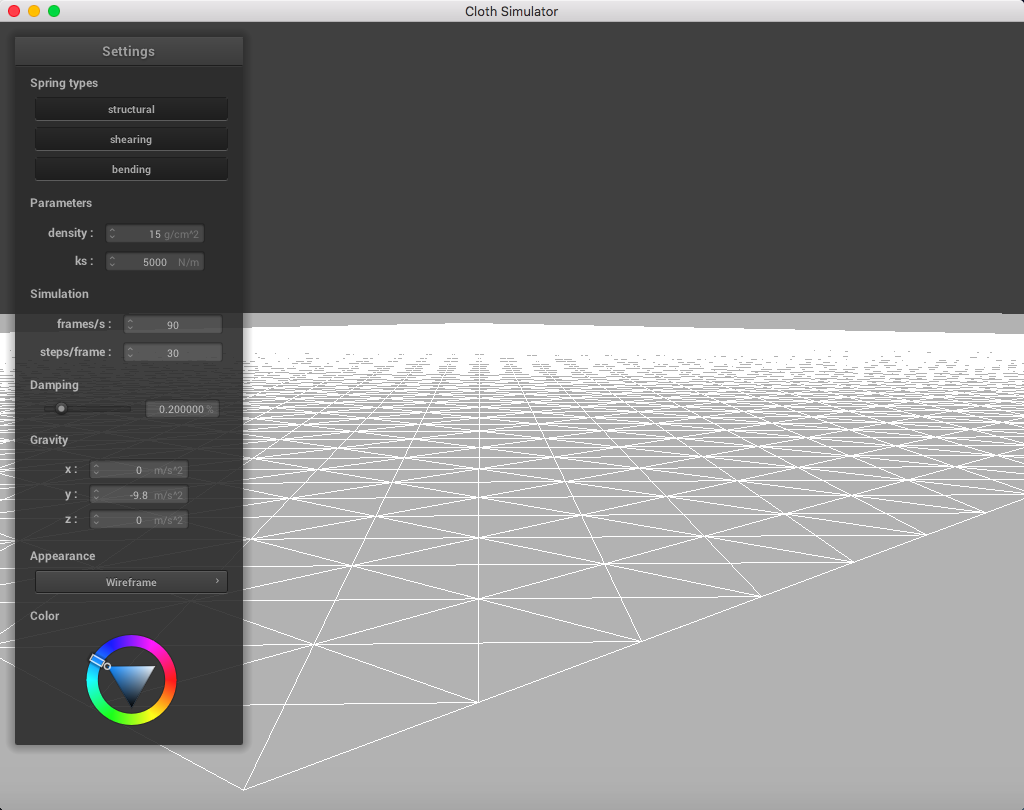

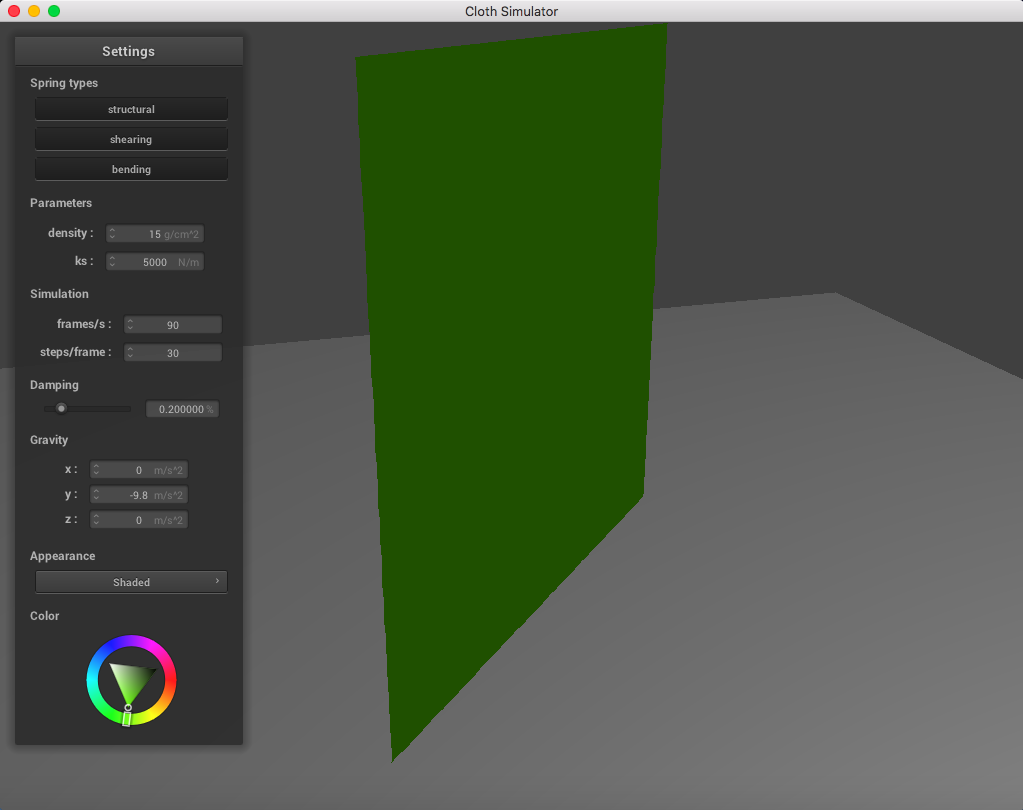

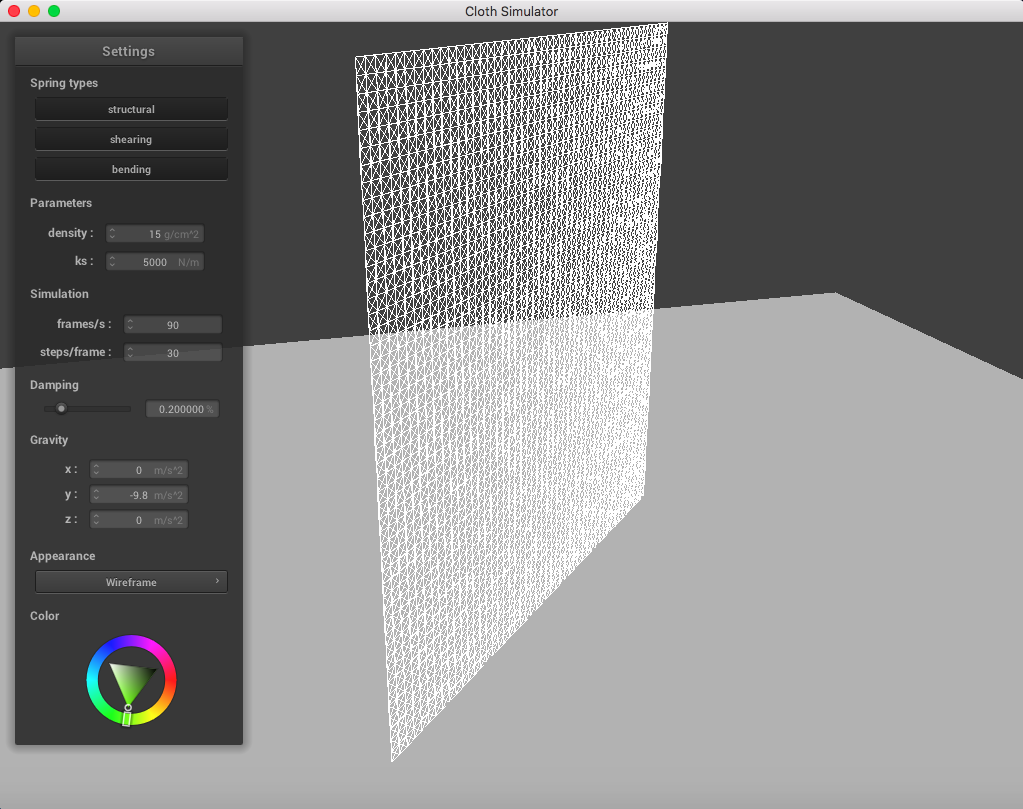

The first thing I implemented in my cloth simulator was a grid to keep track of points in the cloth. I stored the data in a vector that held num_width_points by num_height_points individual masses with their unique coordinates determined by a width and height. If we wanted to have certain points pinned down, I made it so that there is a boolean isPinned for every point which is only true if it is specified that the point mass's index is in the pinned mass vector.

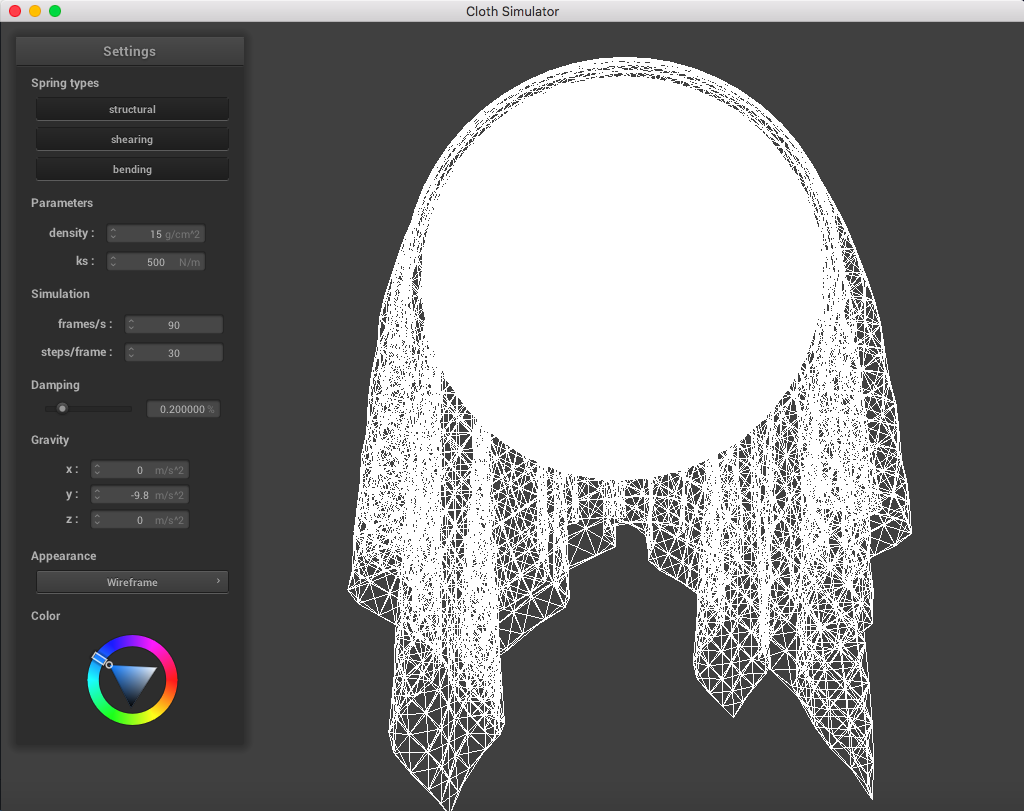

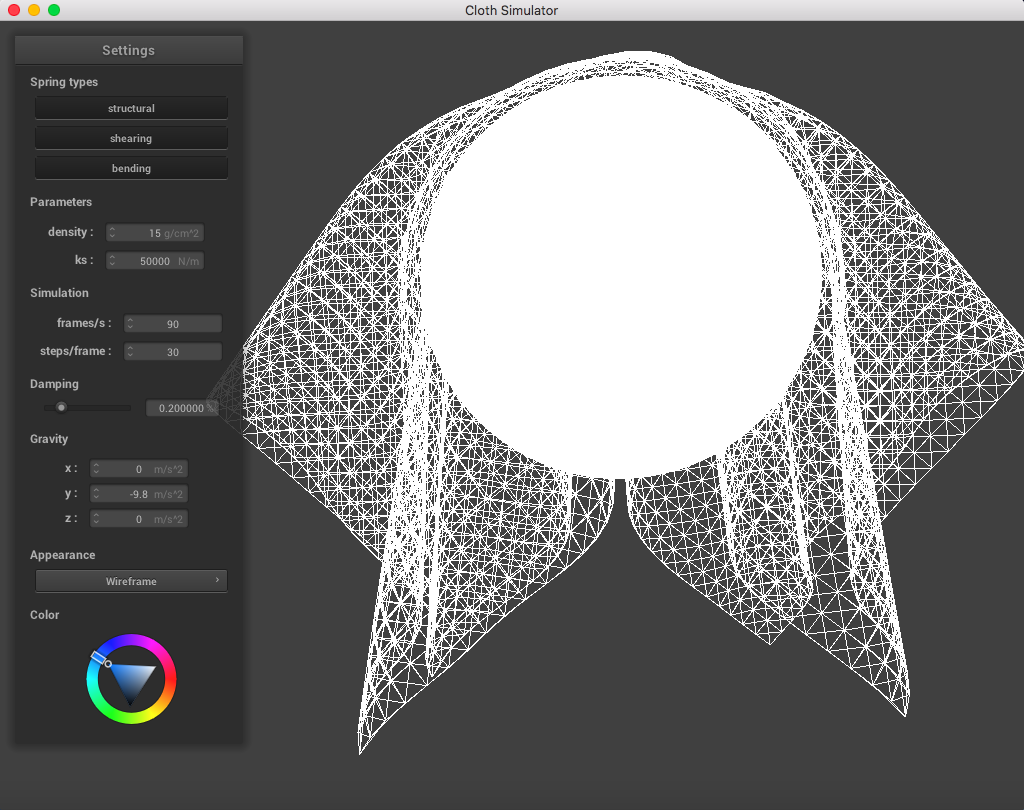

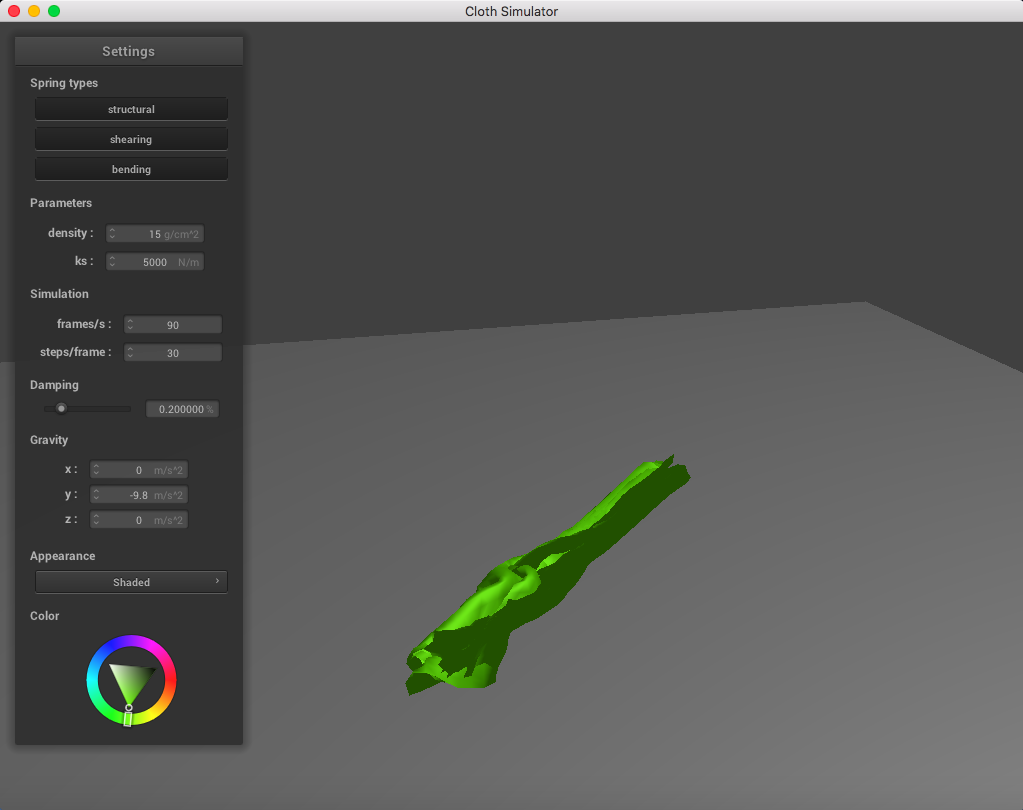

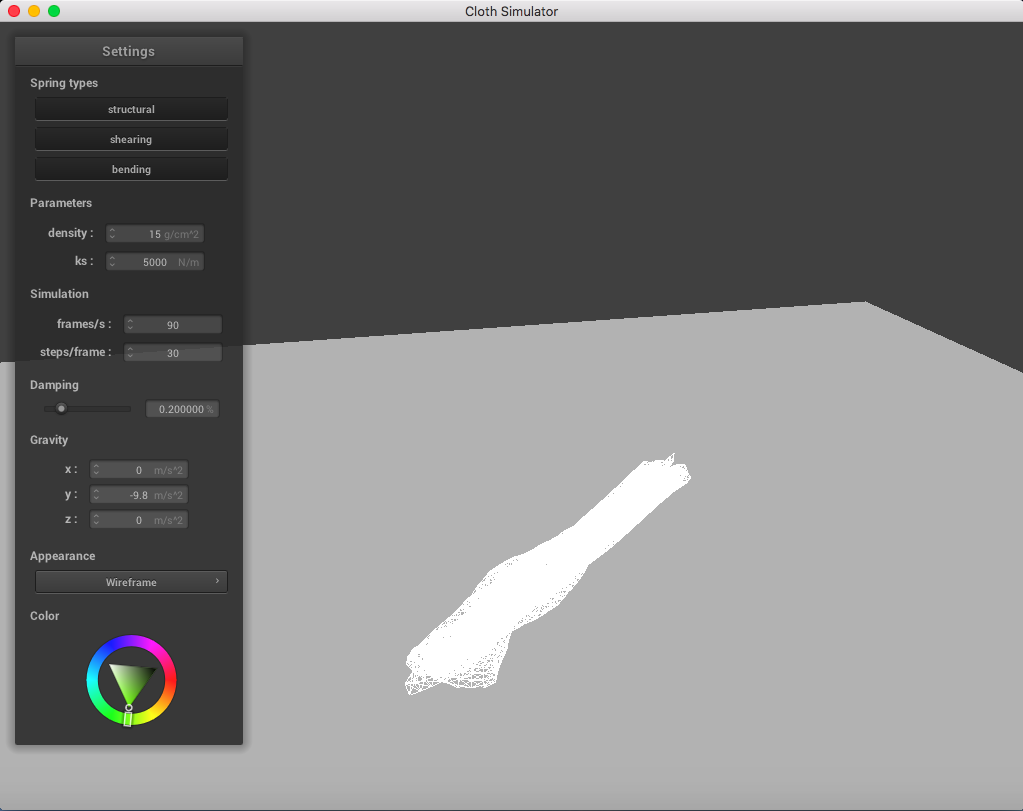

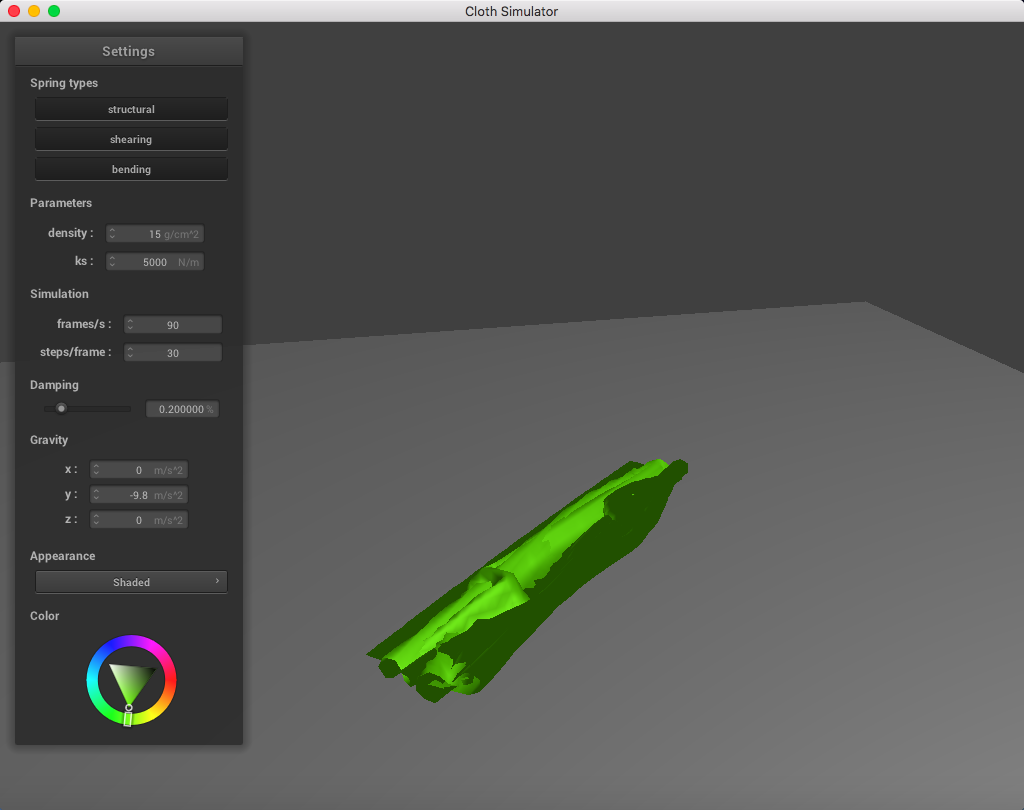

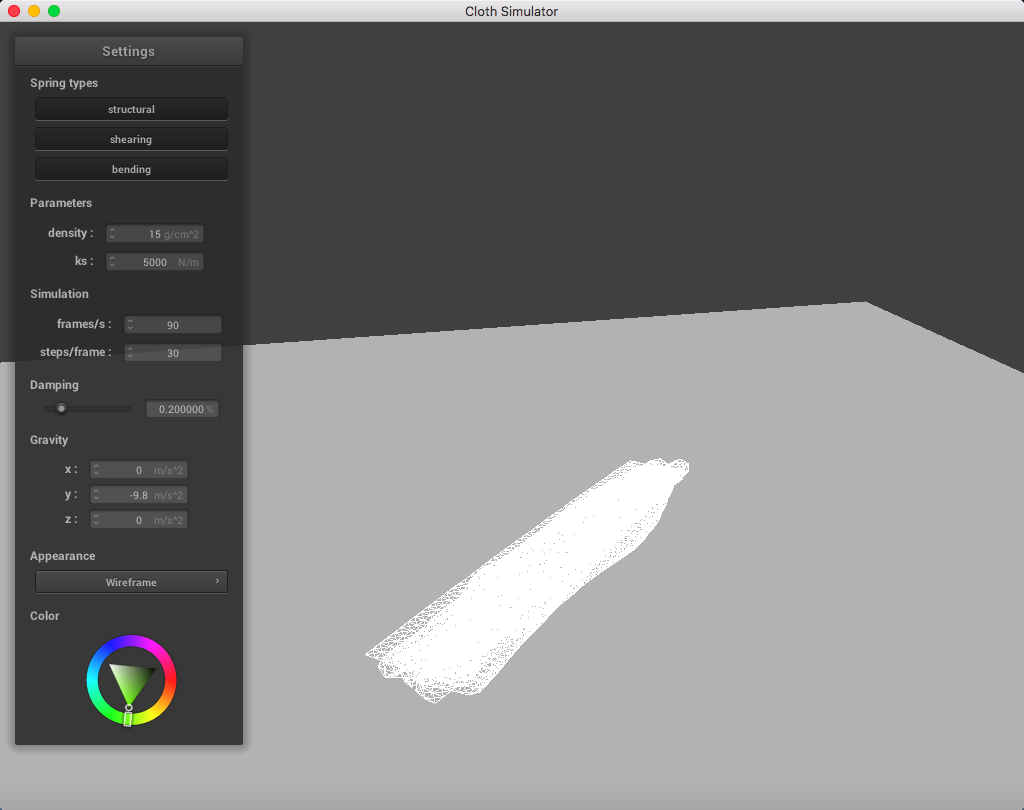

With this grid of points, I created springs that would apply various constraints on the point masses - these three constraints were structural, shearing, and bending, each applying constraints to two point masses in their own way. Structural constraints are between horizontally/vertically adjacent point masses, shearing constraints are between diagonally adjacent point masses, while bending constraints are between point masses that skip over a point mass horizontally or vertically. There were a lot of edge cases I had to account for, which were literally the point masses that were on the edge of the wireframe grid.

|

|

|

|

In this part, I set up the actual simulation for the cloth. How I implemented this was by computing the various forces acted upon each point mass, and calculating the new location of the point mass based on the applied forces as well as its previous position. My simulate function changed the position of the point masses one step at a time. I used Verlet integration to compute the new position of the point masses, which required the last position and a damping constraint in order to calculate velocity, as well as the forces and the mass to calculate acceleration.

Lastly, I added a constraint between the springs such that its two point masses must not exceed 10% more than the rest_length at the end of any time step. To do this, I would "reset" the distance between the points to be at that maximum resting distance in order to preserve the most realistic simulation. This made it so that the cloth would not end up very deformed and unreasonably stretched out.

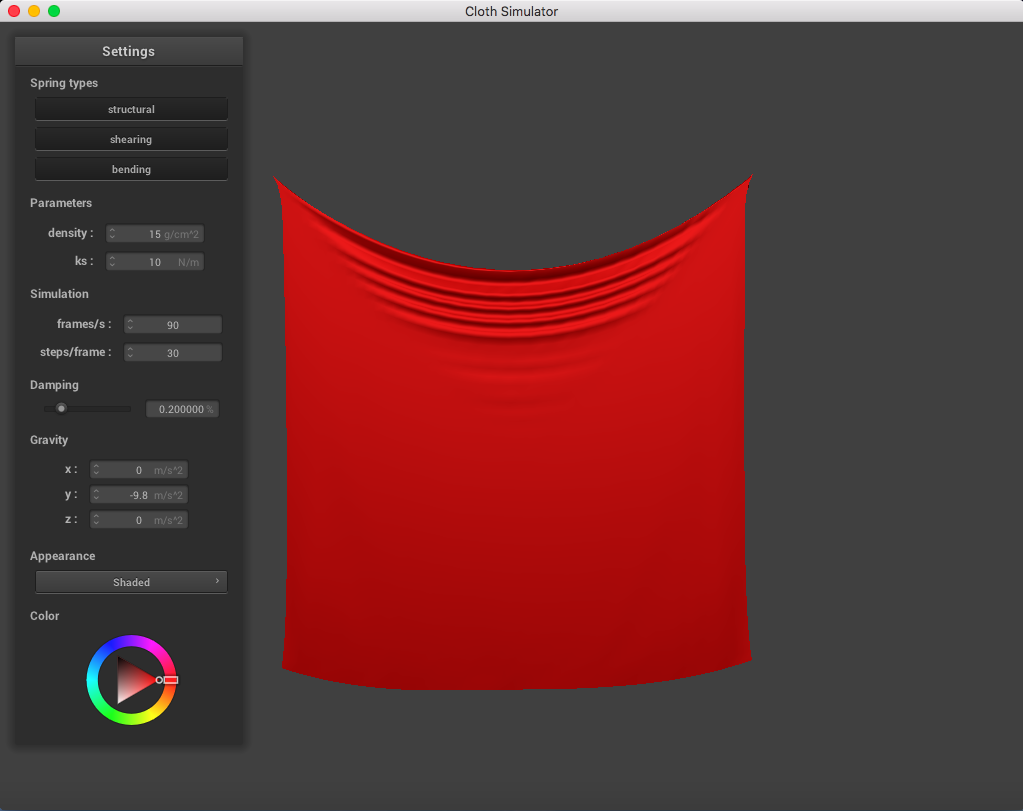

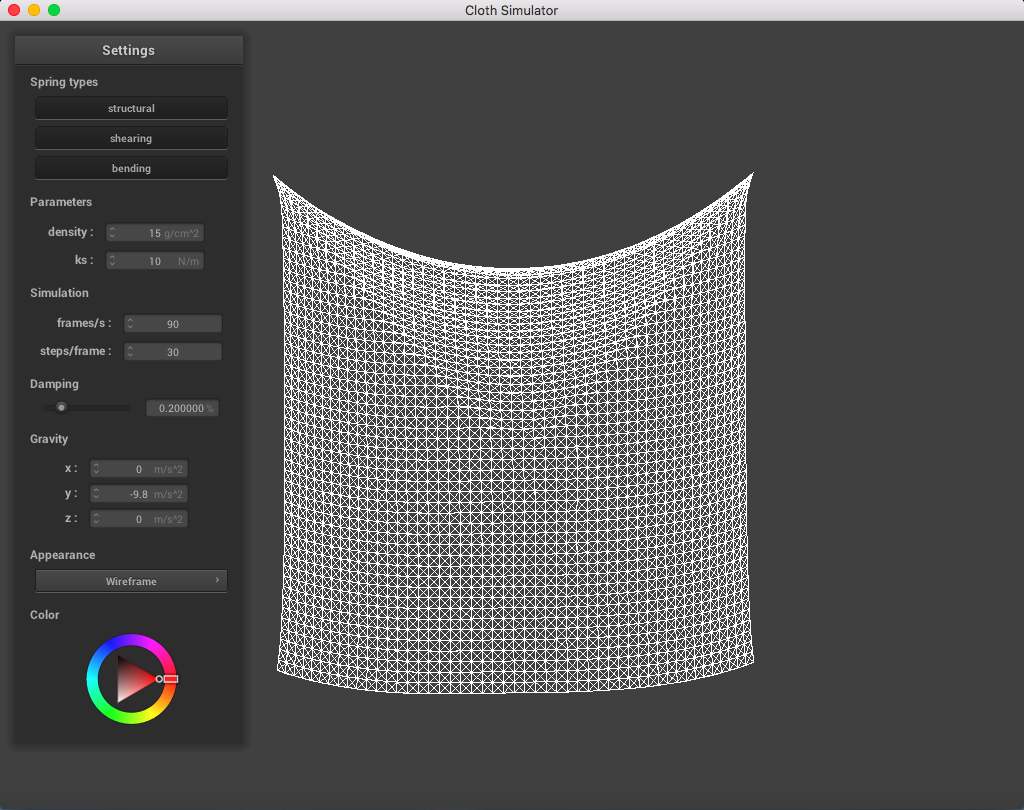

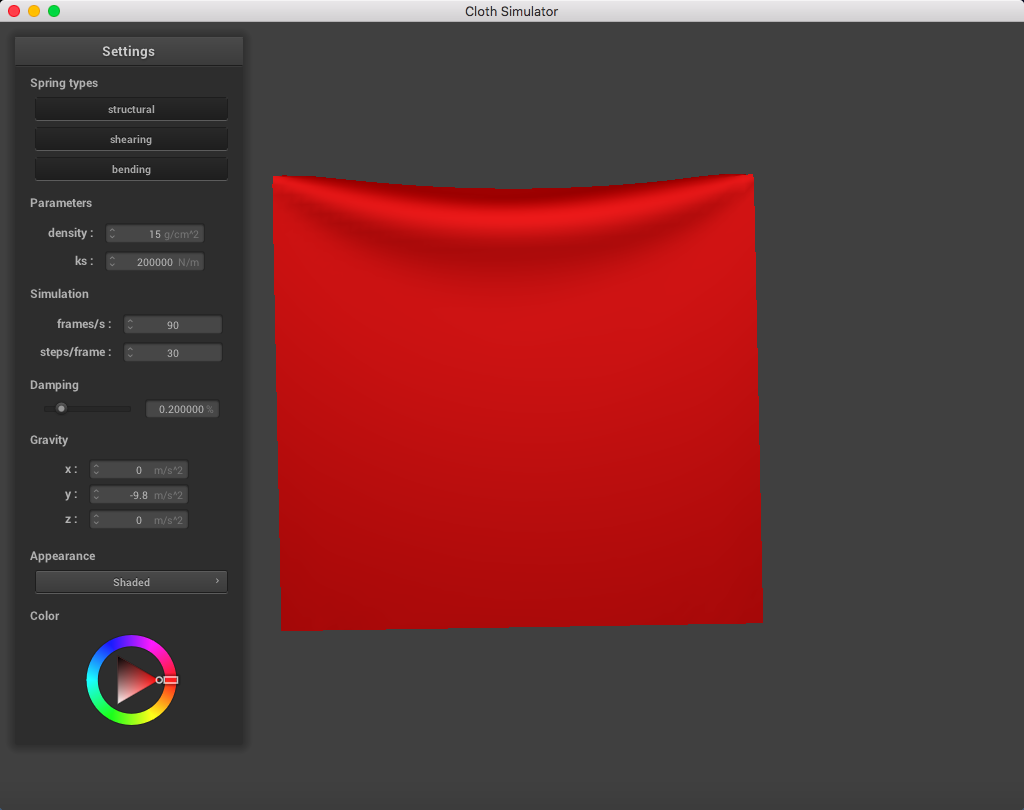

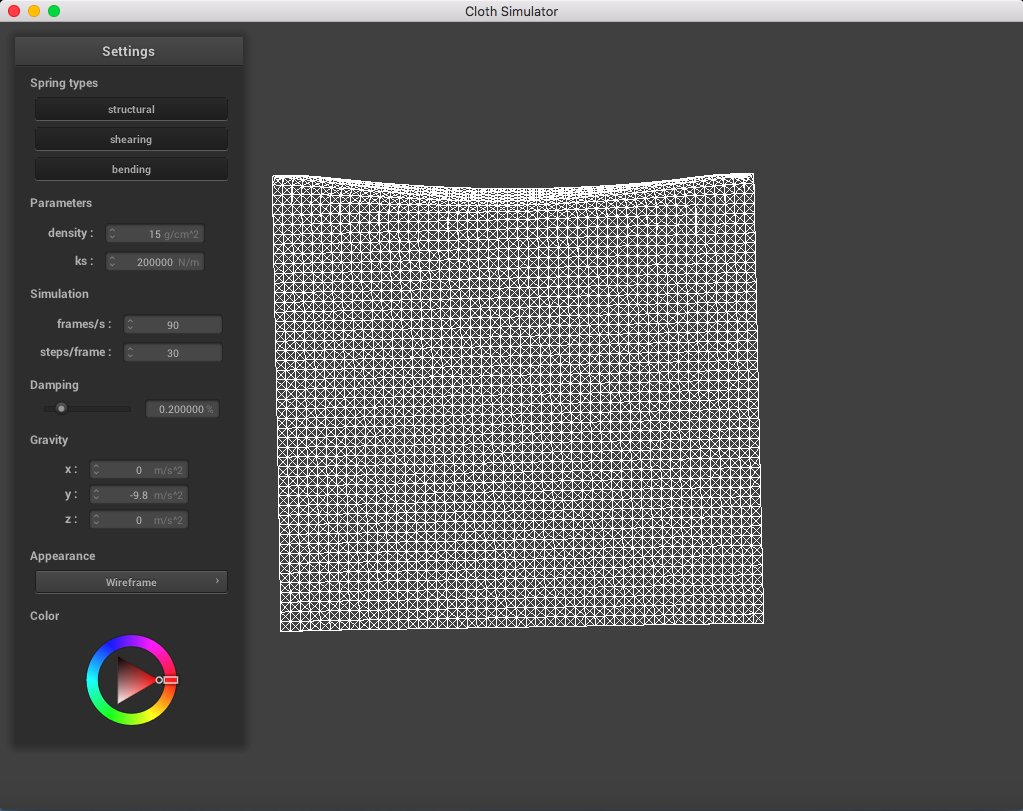

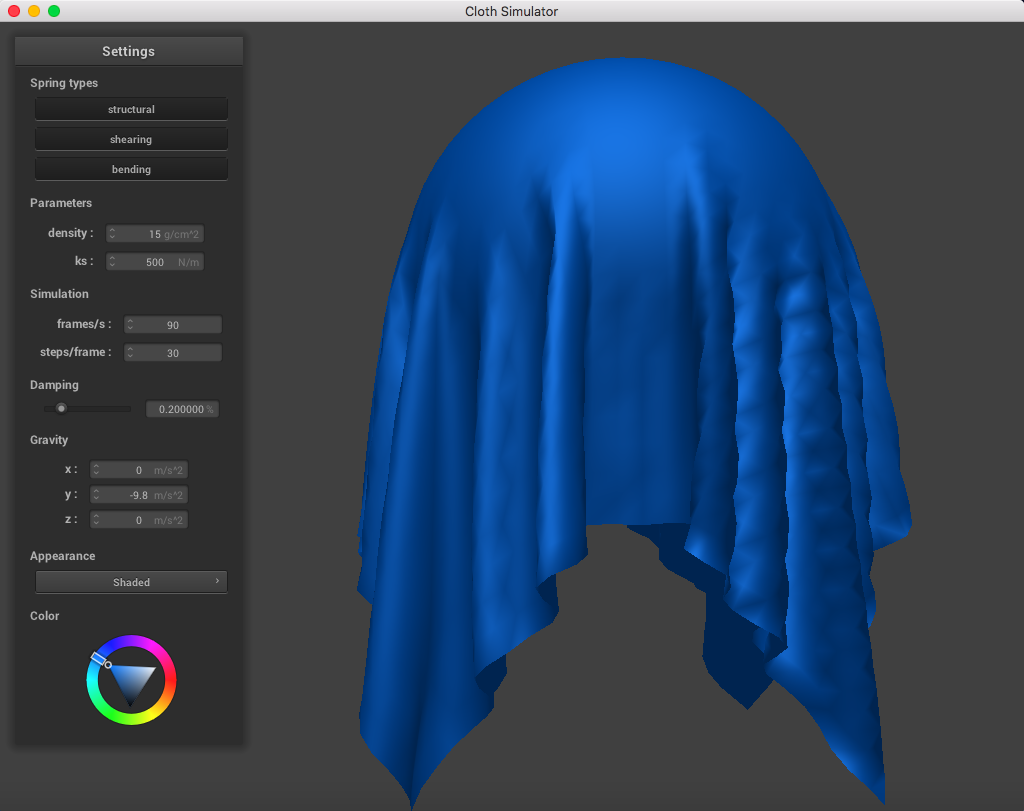

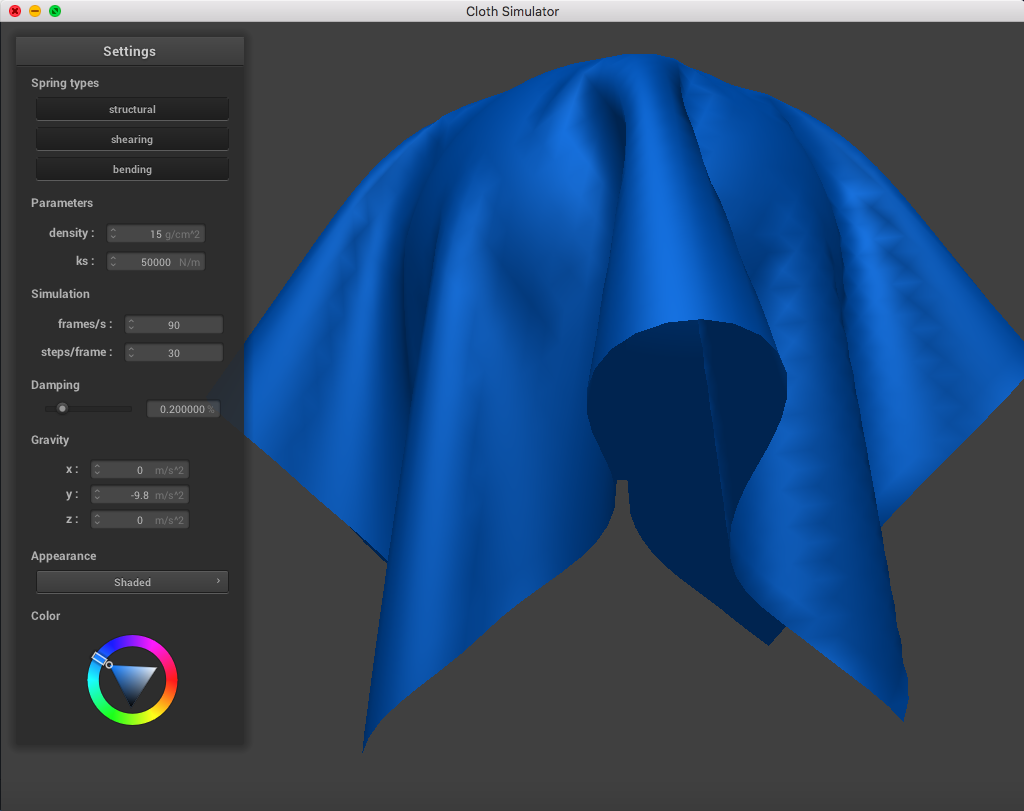

When playing around with the spring constant ks parameter (while maintaining density = 15 g/cm^2, damping = 0.2%), I noticed that a lower spring constant made the fabric seem loose and stretchier, while a higher spring constant correlated to a stiffer cloth fabric.

|

|

|

|

When changing just the density parameter (maintaining ks = 5,000 N/m, damping = 0.2%), I could tell that a lighter density represented a lighter mass. The cloth drooped less than it did normally, compared to a much high density which sank more and had more prominent folds in the cloth.

|

|

|

|

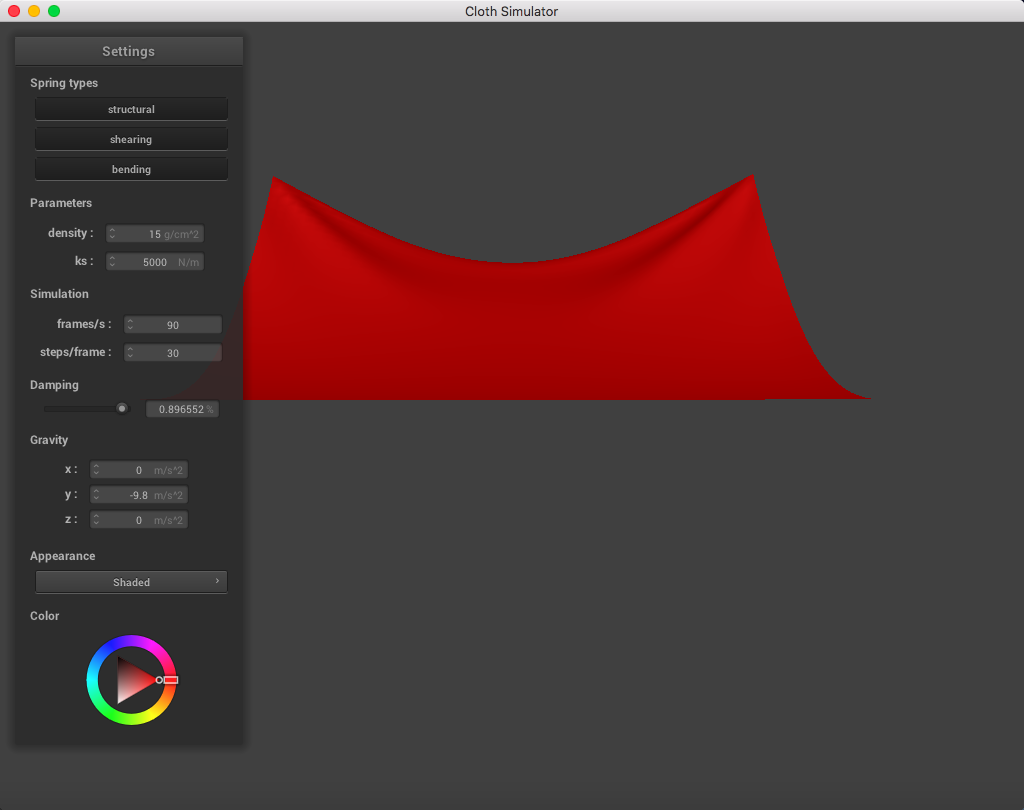

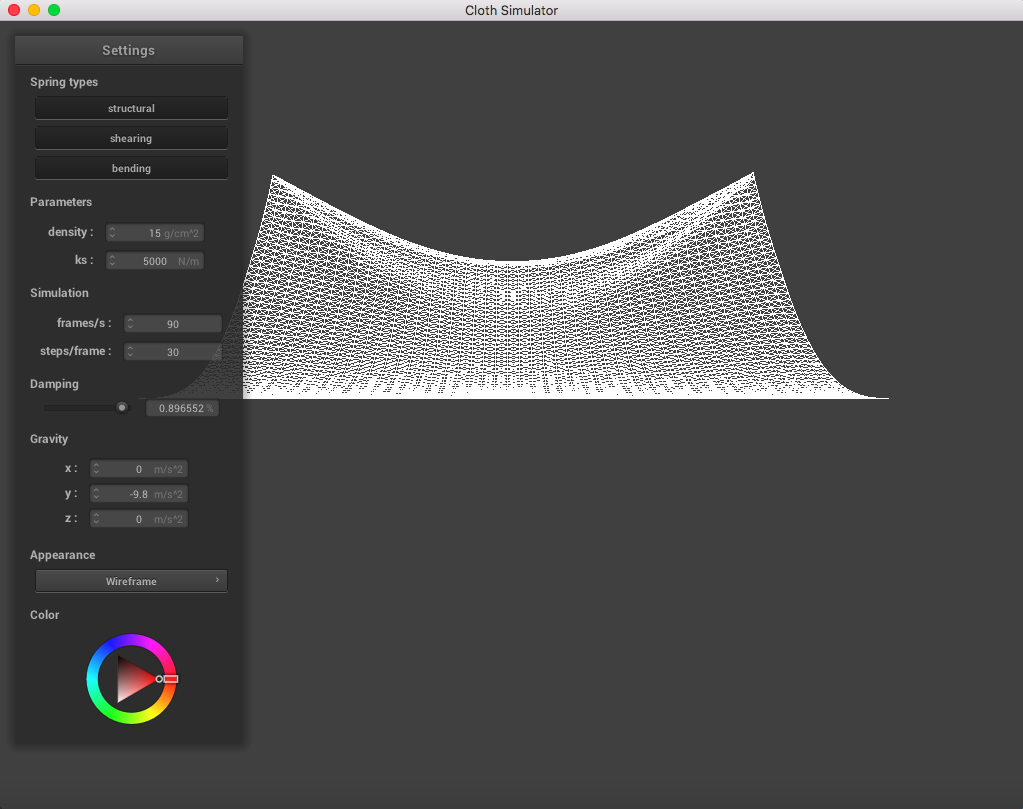

When changing the damping parameter (with the constant parameters density = 15 g/cm^2, ks = 5,000 N/m), there was a clear distinction that a lower damping constant made the cloth fall down faster and was more bouncy, versus a higher damping constant which fell slower and didn't move around that much (didn't really swing after reaching the bottom). The damping constant is pretty much the amount of energy that is lost when moving between steps (lower damping will make the cloth have much more energy than one with higher damping).

|

|

|

|

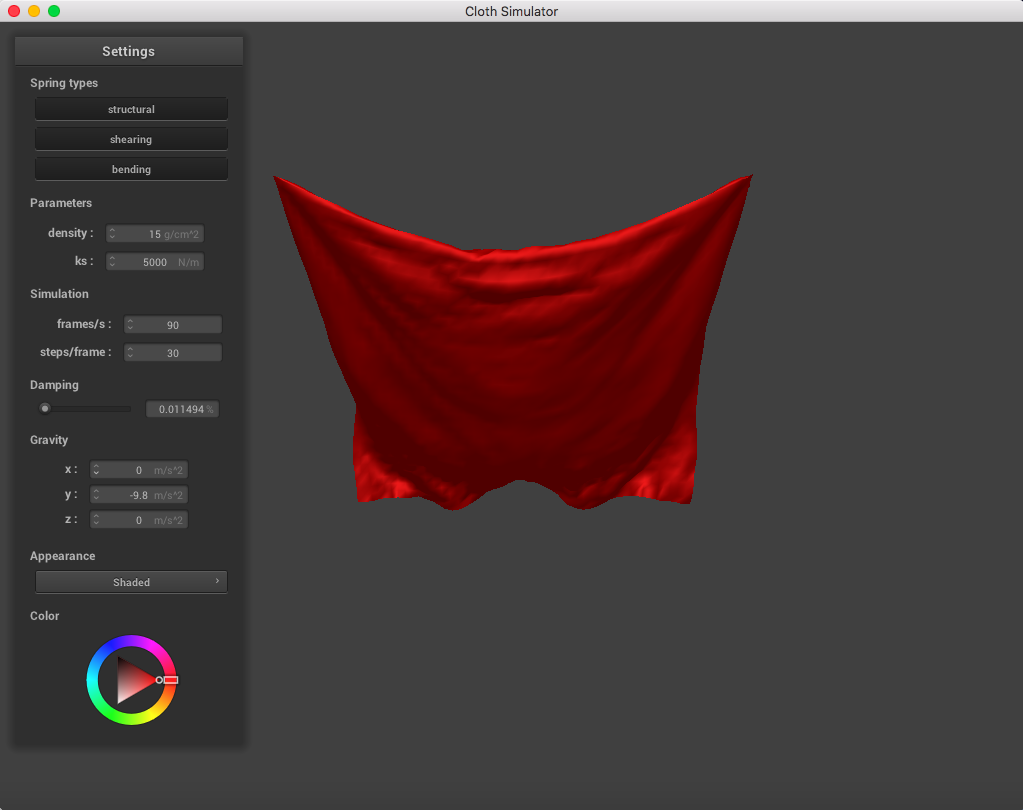

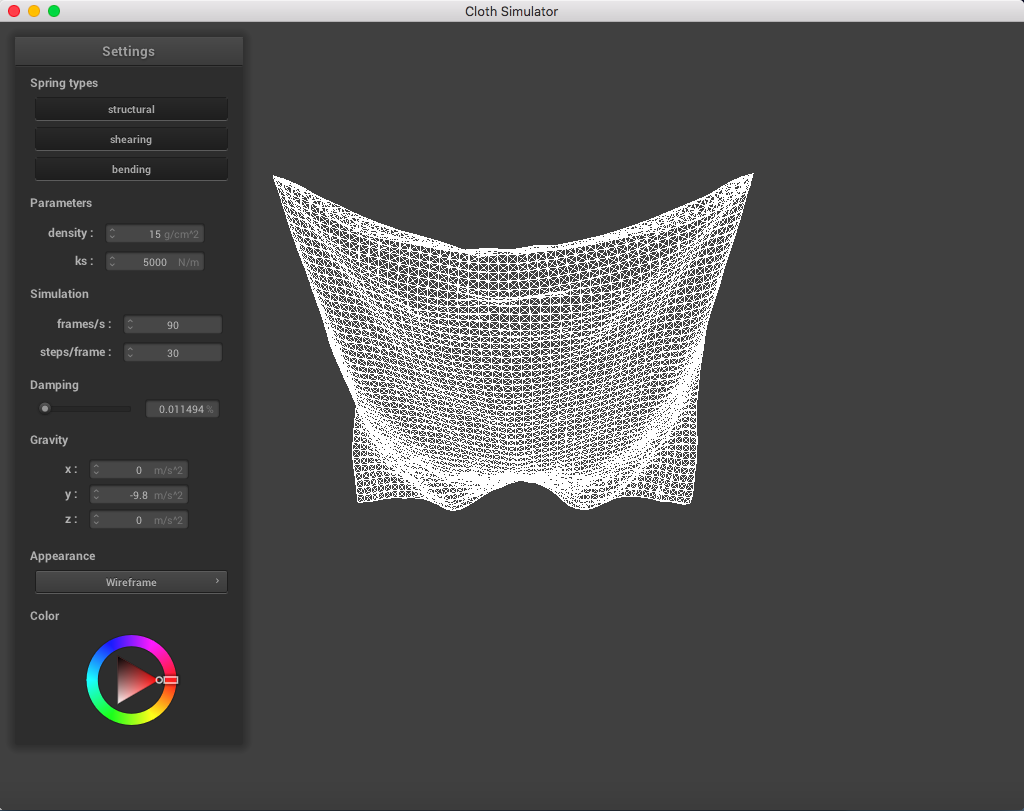

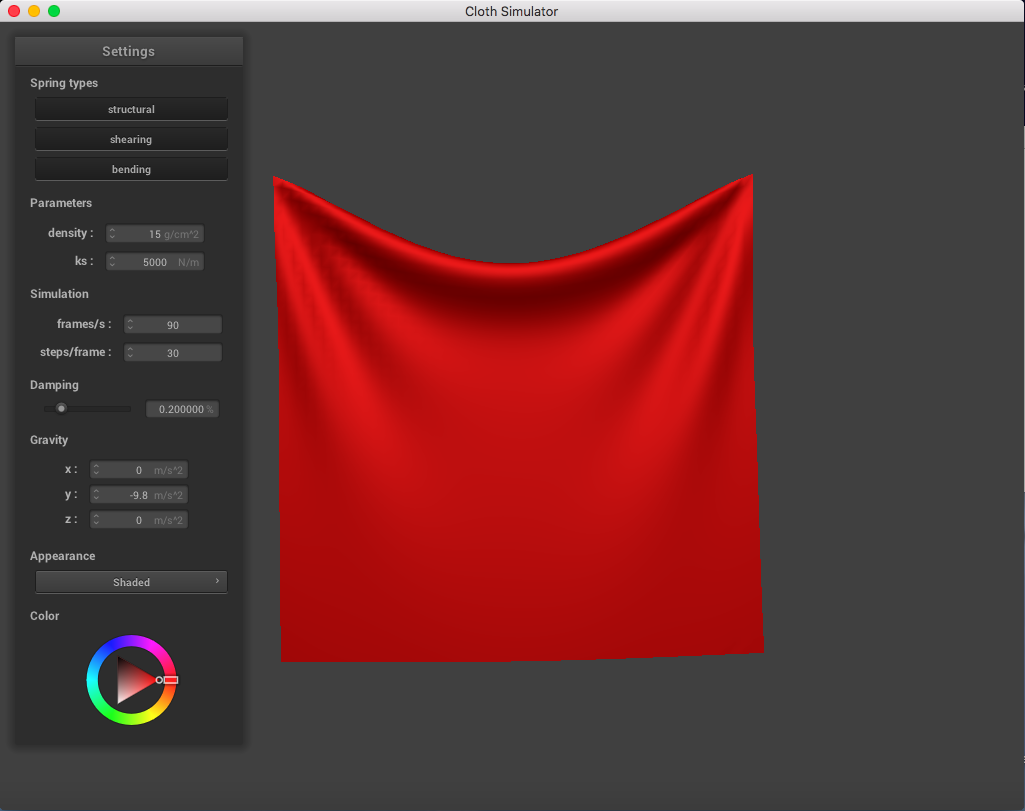

The following image is a screenshot of the pinned4.json in its resting state using the standard parameters (density = 15 g/cm^2, ks = 5,000 N/m, damping = 0.2%), which may be used as a reference image for all of the adjusted parameters (middle ground for each of the pairs of extremes):

|

|

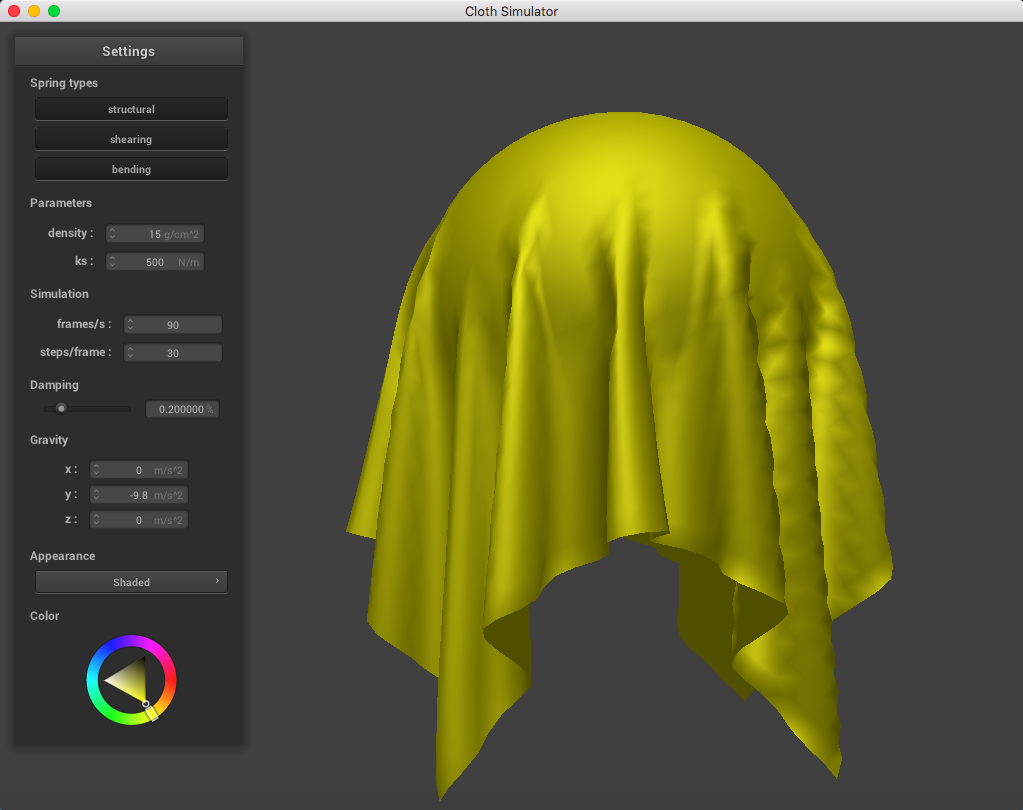

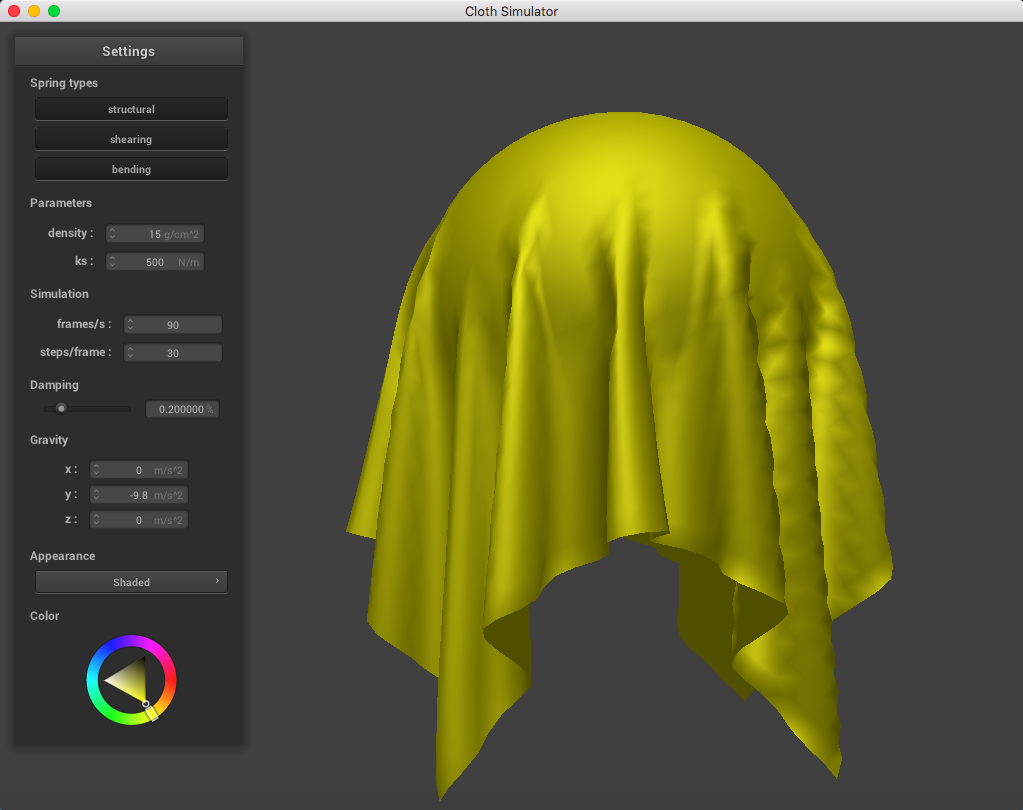

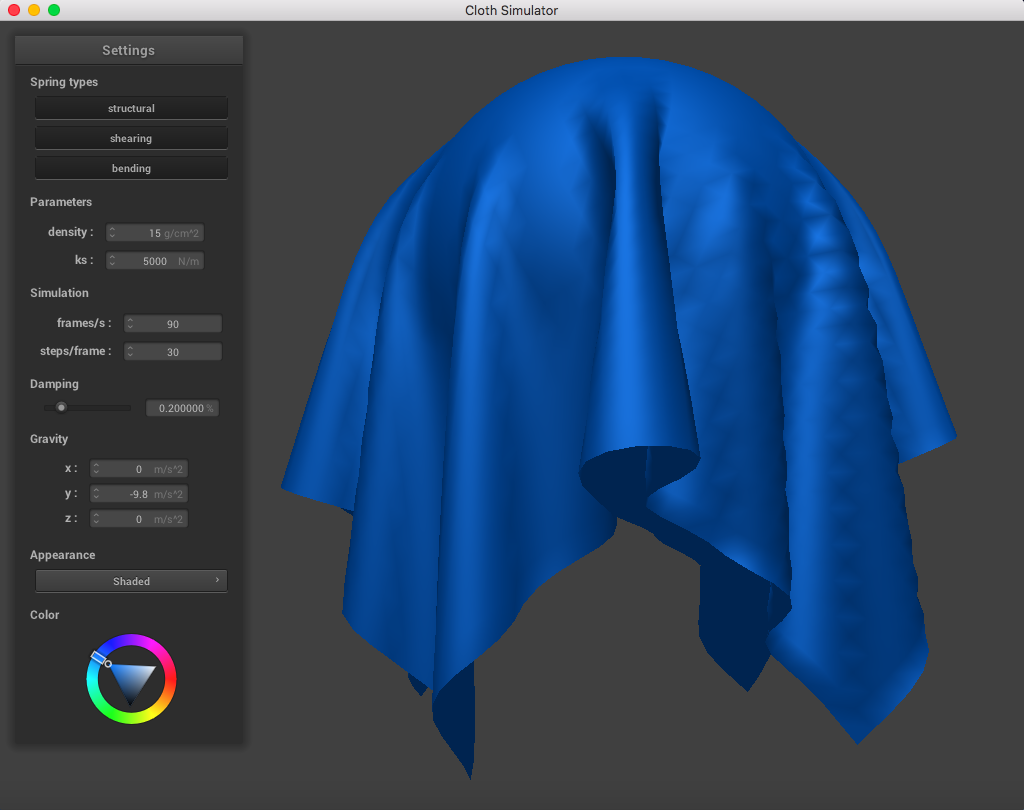

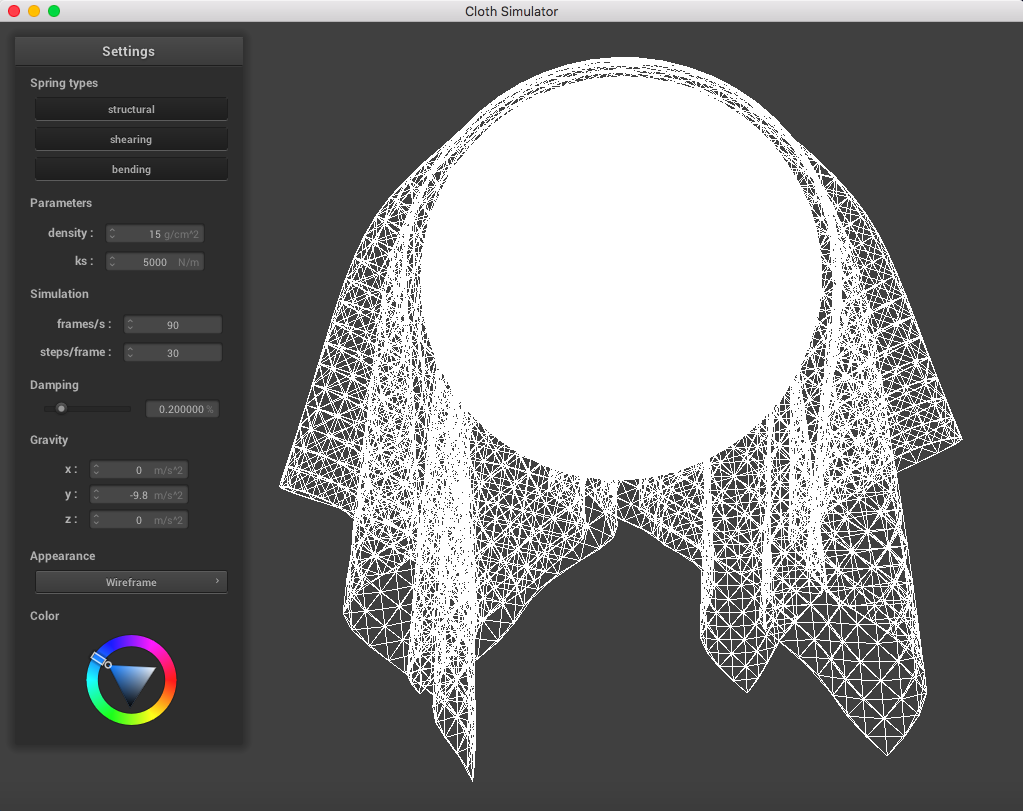

In this section, I determined how the cloth would act with other objects. I first implemented a method to check if a point mass collided with a sphere - if the point mass coordinate was within the sphere's radius, I changed the current position to be a corrected vector based on its previous point and a scaling factor based on friction. When comparing the simulation with different spring constant ks, I noticed that a higher spring constant led to a cloth that did not resemble a sphere shape as well as a cloth with a lower ks (a lower ks appeared to be much more looser than a higher ks which was stiffer). A higher ks results in a larger force vector pointing in between the two points of each spring, so that means the grid point masses would prefer to stay closer together.

|

|

|

|

|

|

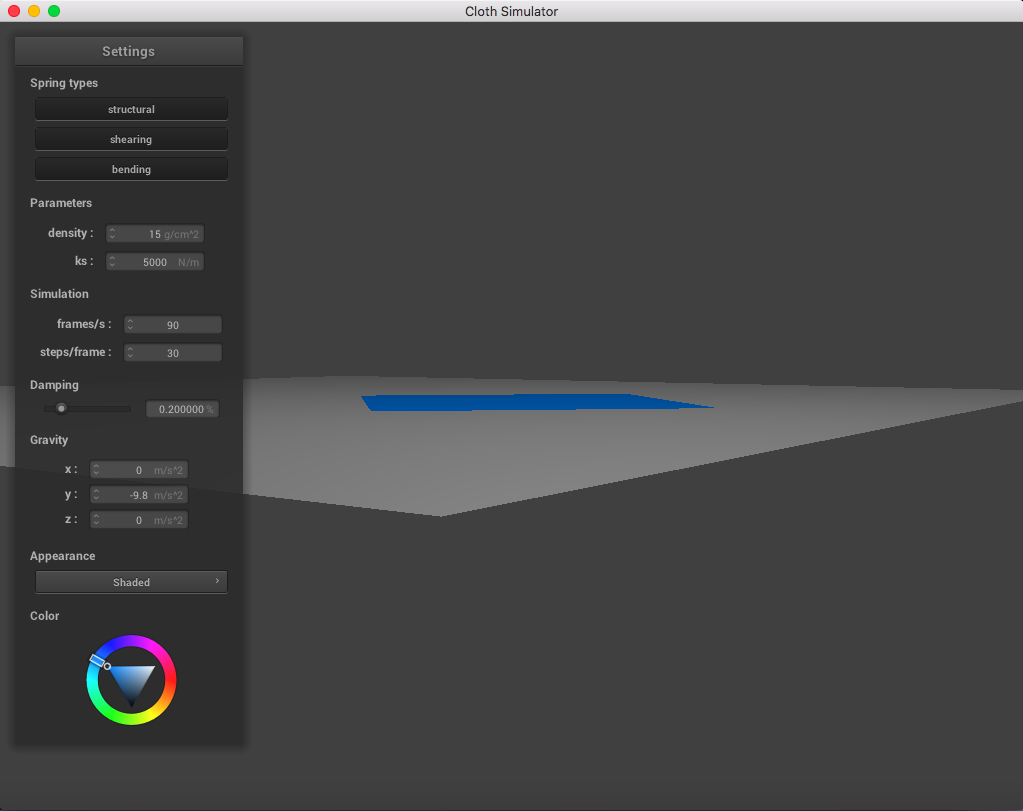

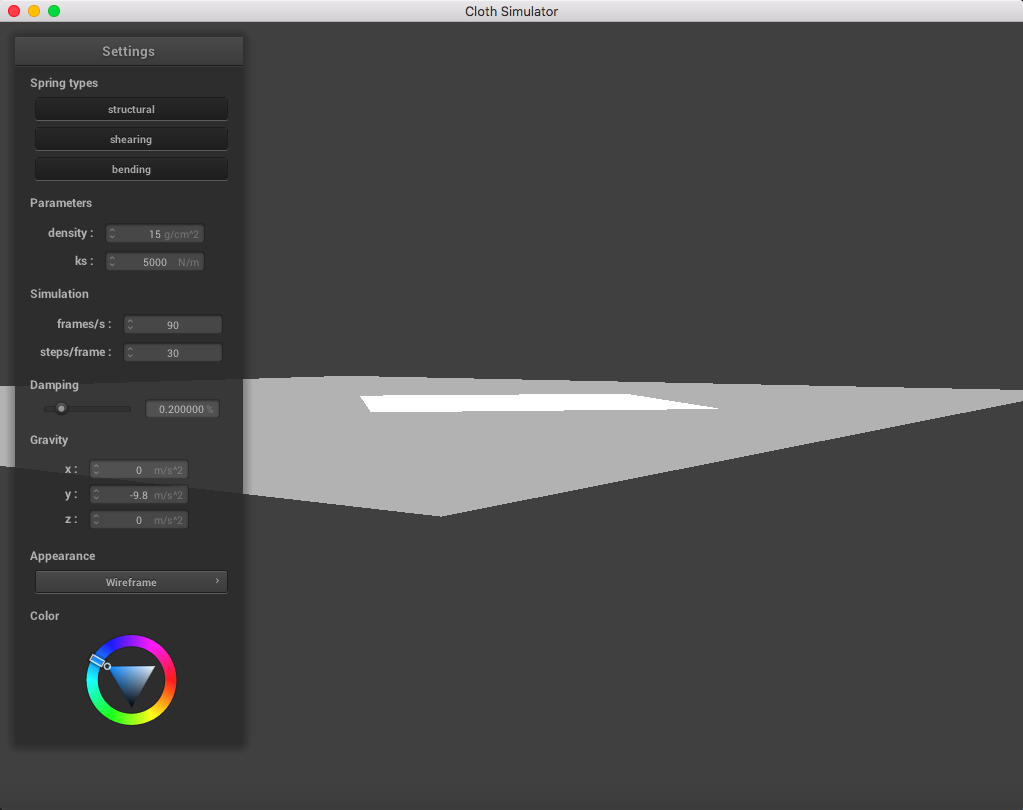

I also implemented the collision with a plane scenario. In order to do this, I had to determine if the current position crossed the plane, and adjust it so that it would lie on top of the plane. I used the point mass's previous position to compare if the current position lied on a different side of the plane than the previous position. If so, I calculated the tangent point of intersection and used this for my correction vector. Afterwards, I set the current position to be the previous position added with a scaled correction vector for friction, with a scaled offset so that the cloth wouldn't be lying directly inside the plane.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A problem for collisions that we have not looked at yet is the case that the cloth point masses intersect with itself at different point masses. It is possible for us to be able to just check for intersection by iterating through all of the point masses for each point mass, but this would be inefficient and slow (with an n^2 runtime). To resolve this, I constructed a hashing method as follows:

I created a 3 dimensional grid of cubes that would store a vector of point masses if a point mass was located inside that small volume. Each cube would be given a unique hashing value so that we can access a specific cube efficiently. This allowed me to check point masses that were close together instead of checking unneccessary point masses that were far apart and did not intersect with the point mass in question. When performing my self_collid method, I looked at the point masses that were within the same cube as the current point mass, and if the length between the two point masses was closer than a specified length (2 * thickness), I would calculate a correction vector that would place the current point mass 2 * thickness away from the other point mass. I accumulated these correction vectors, and divided them by simulation_steps to get a final correction vector to actually apply to the current point mass's position.

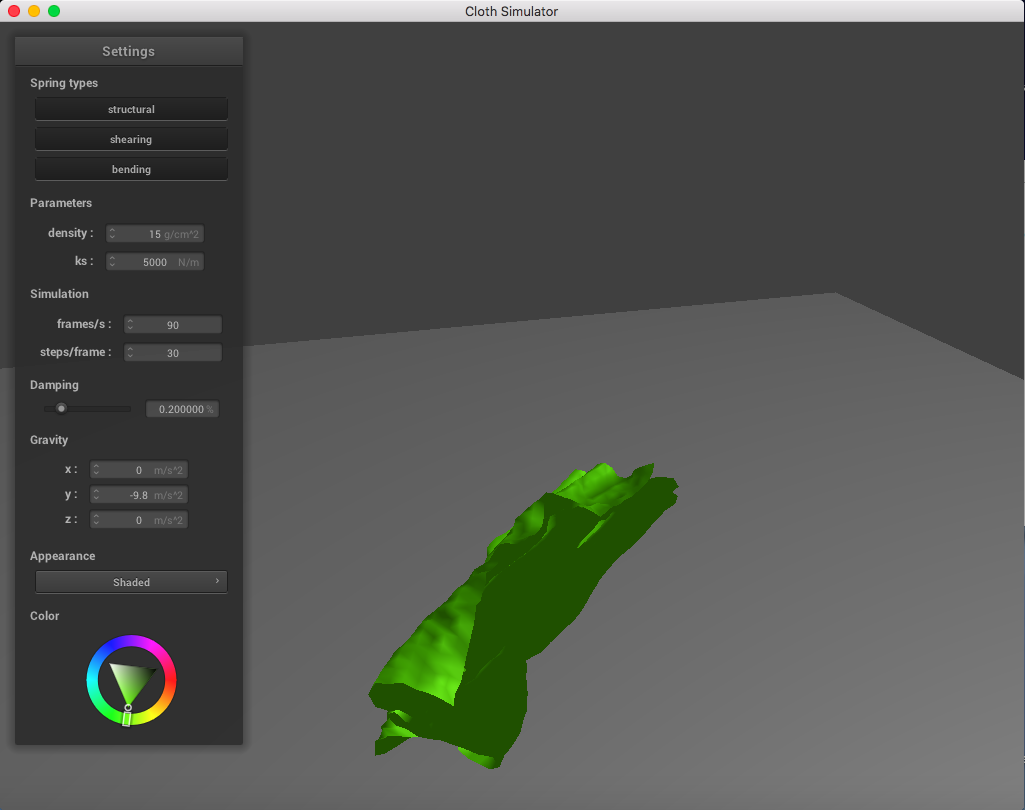

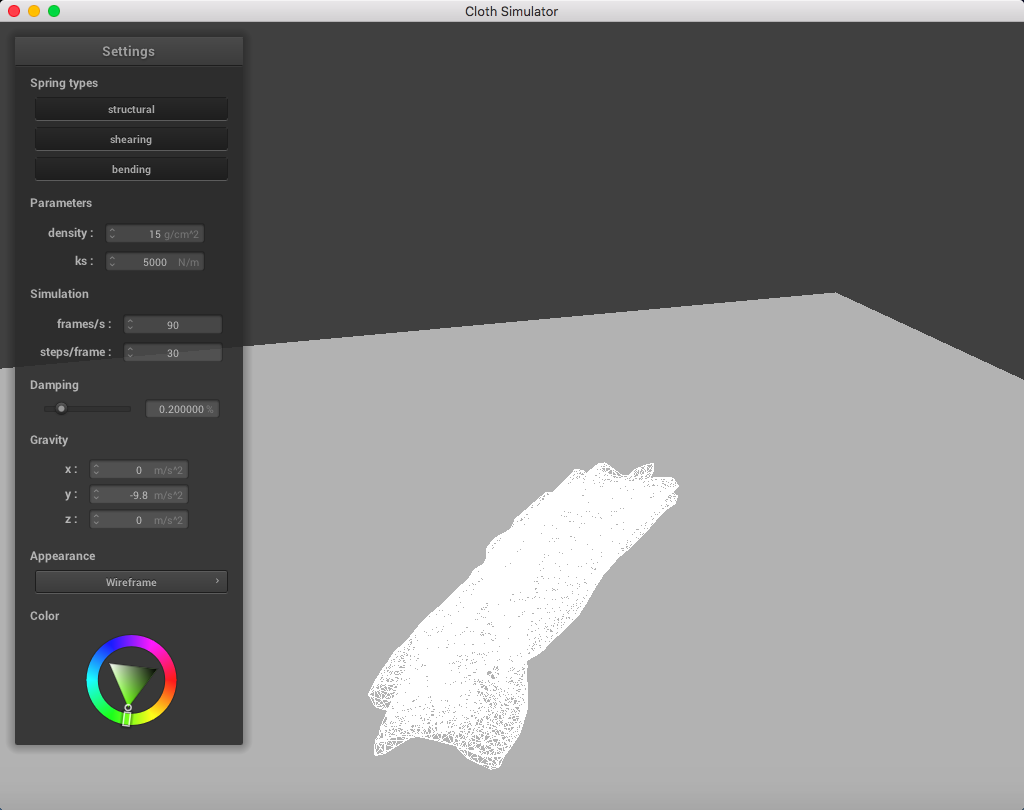

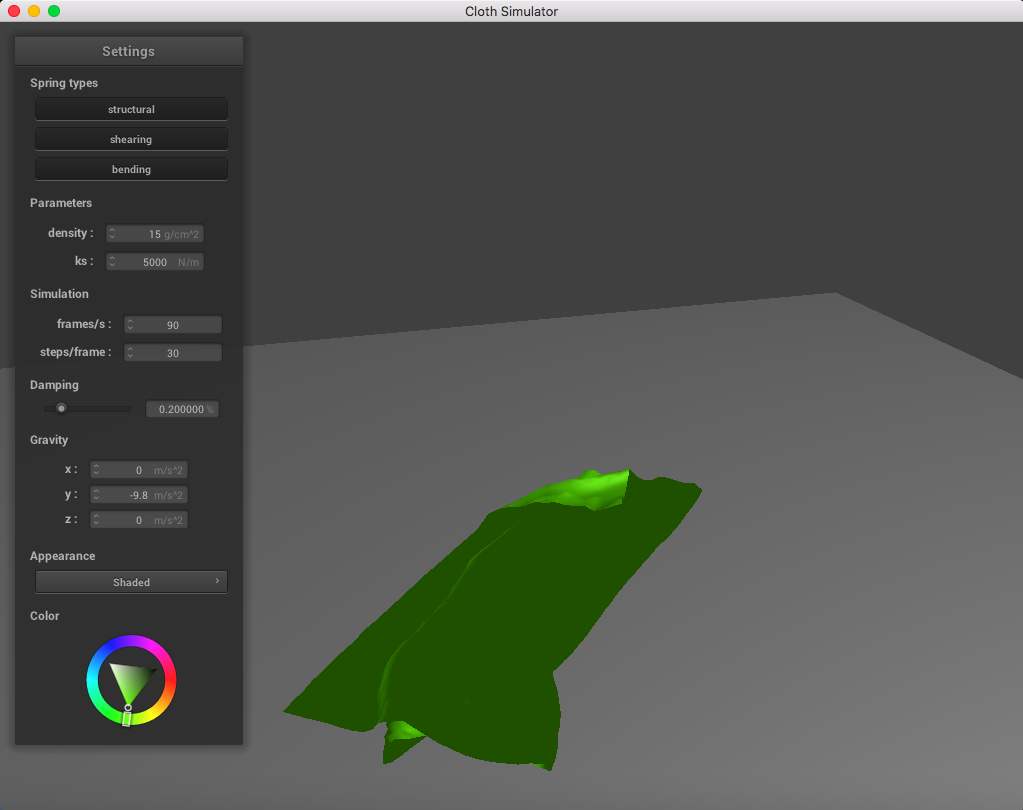

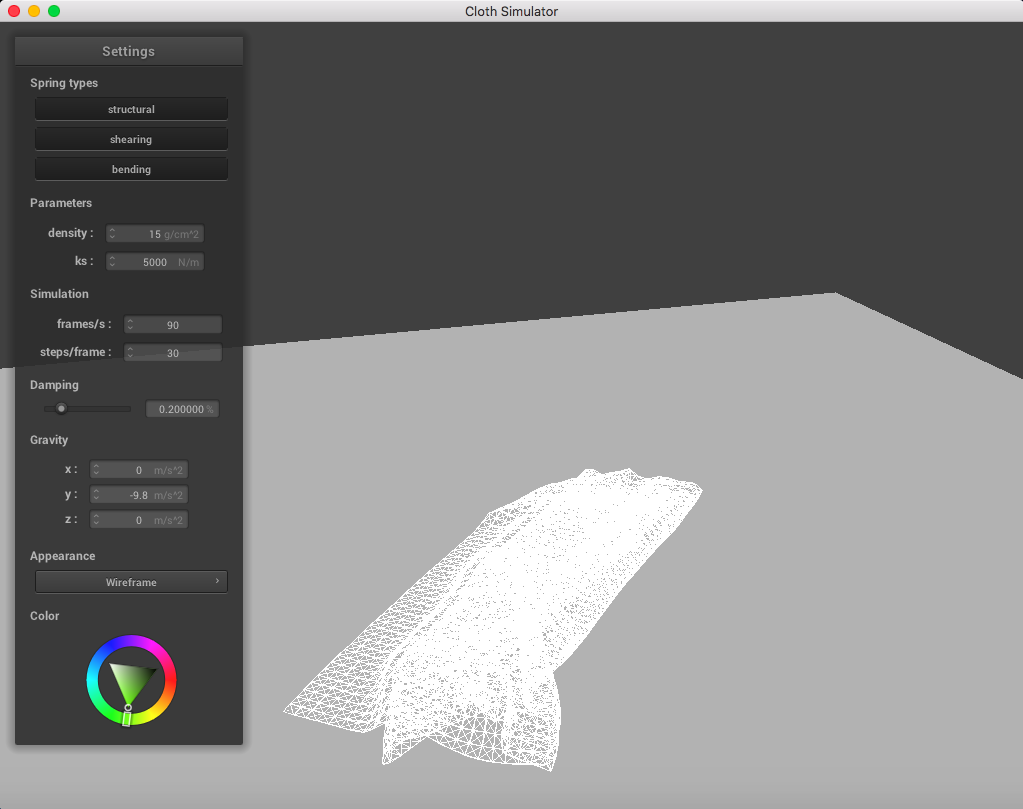

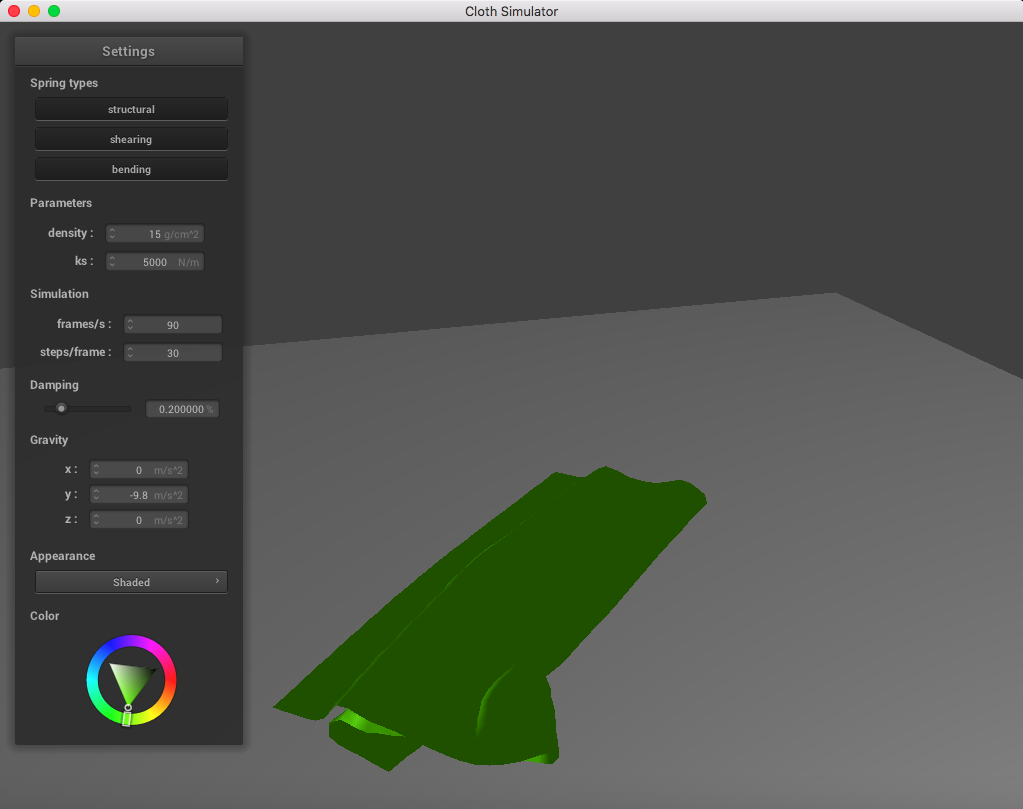

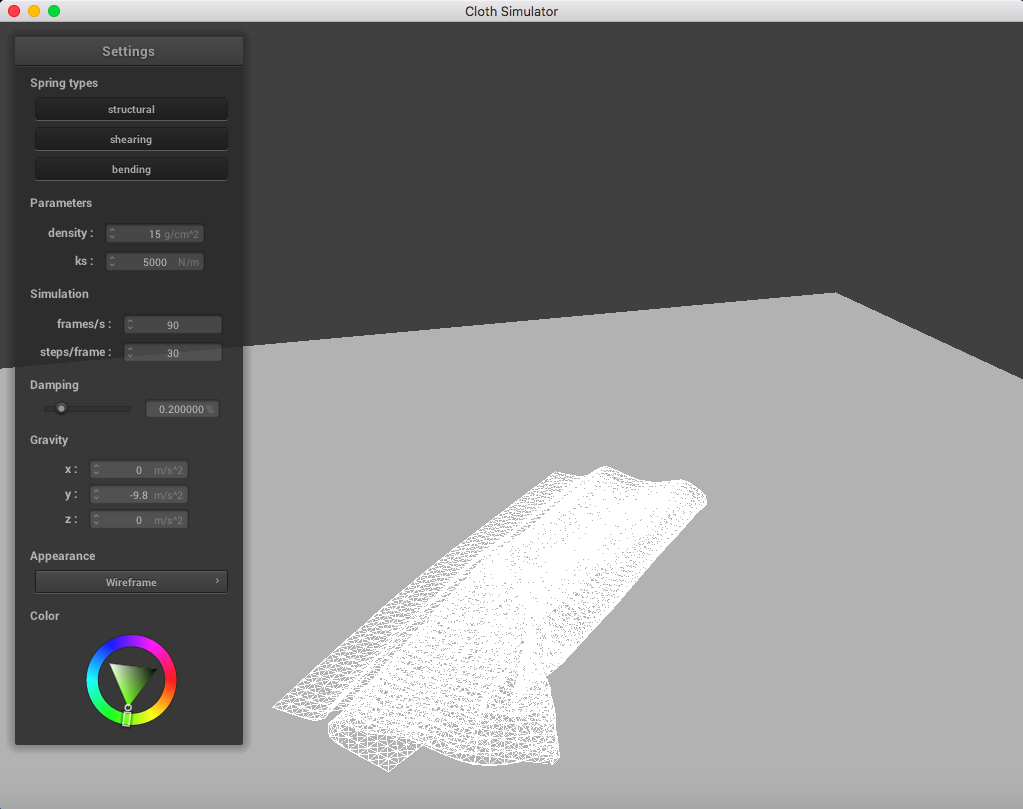

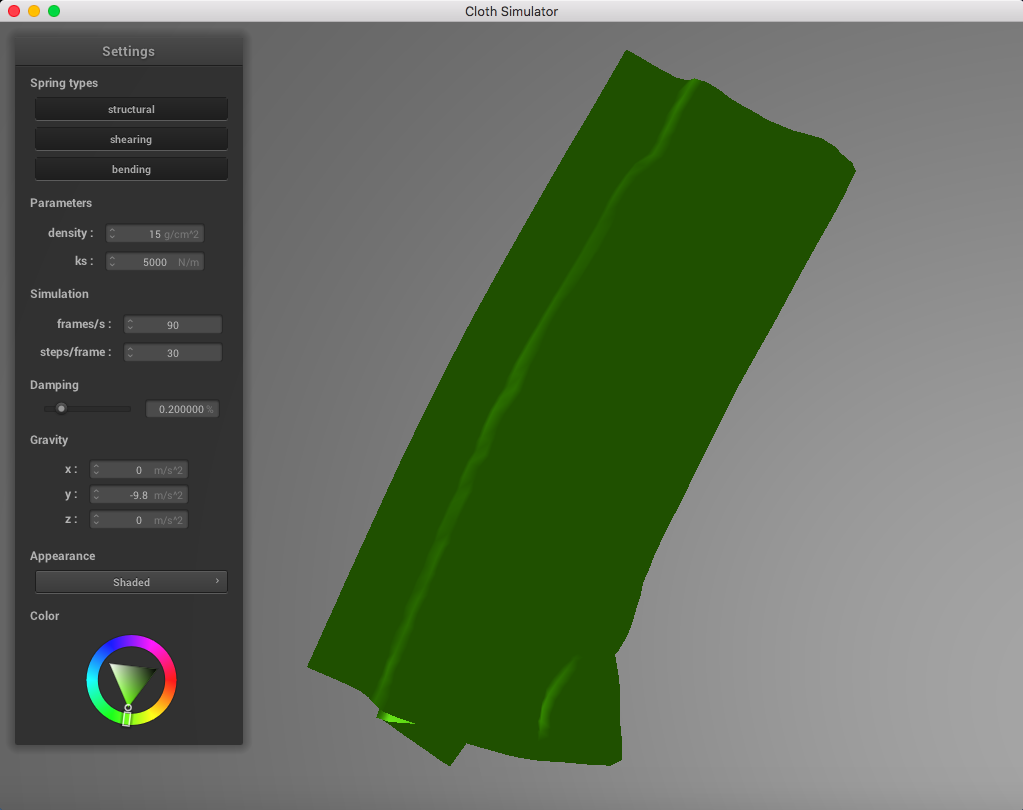

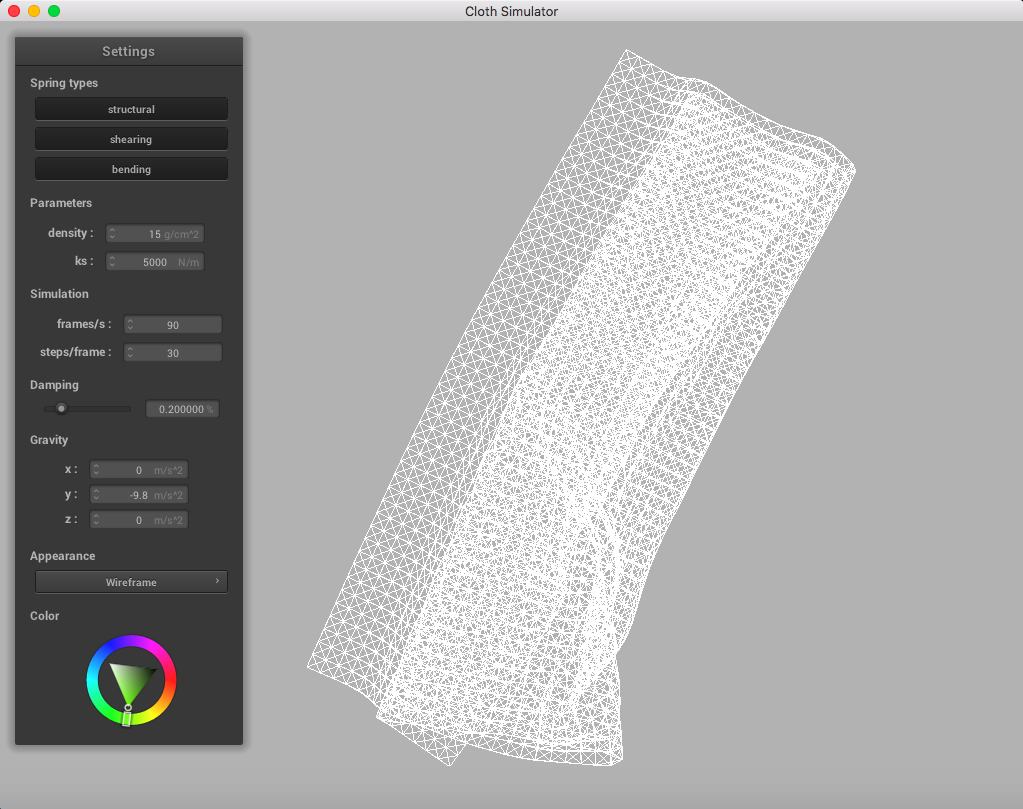

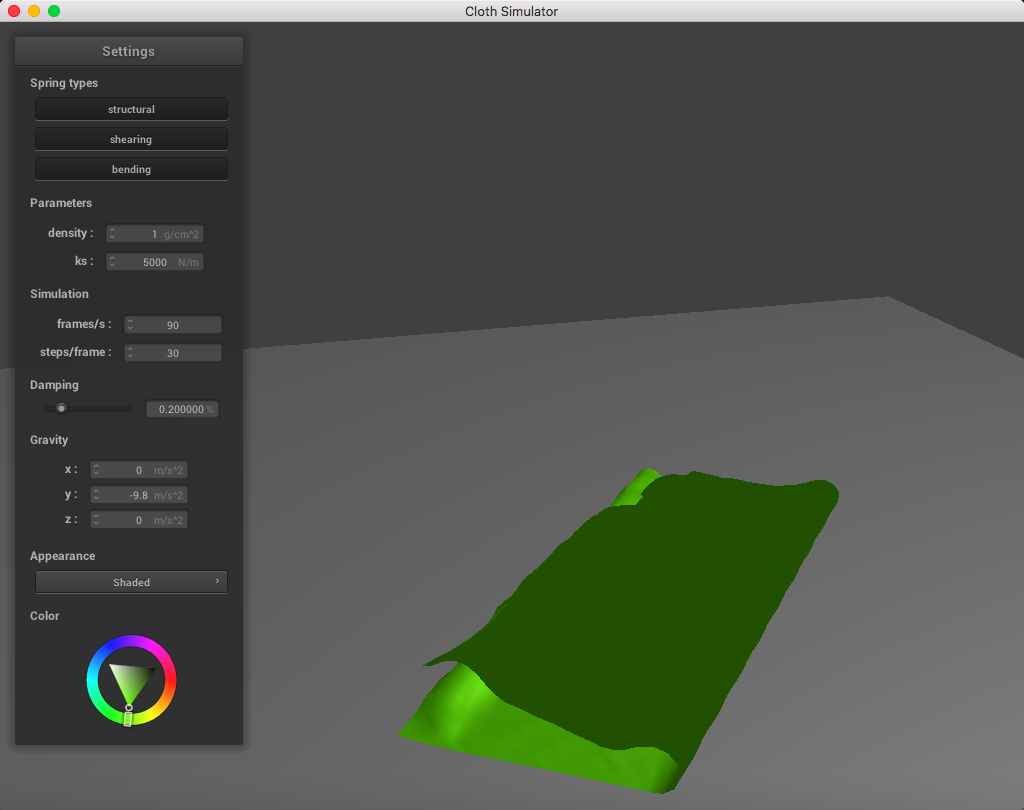

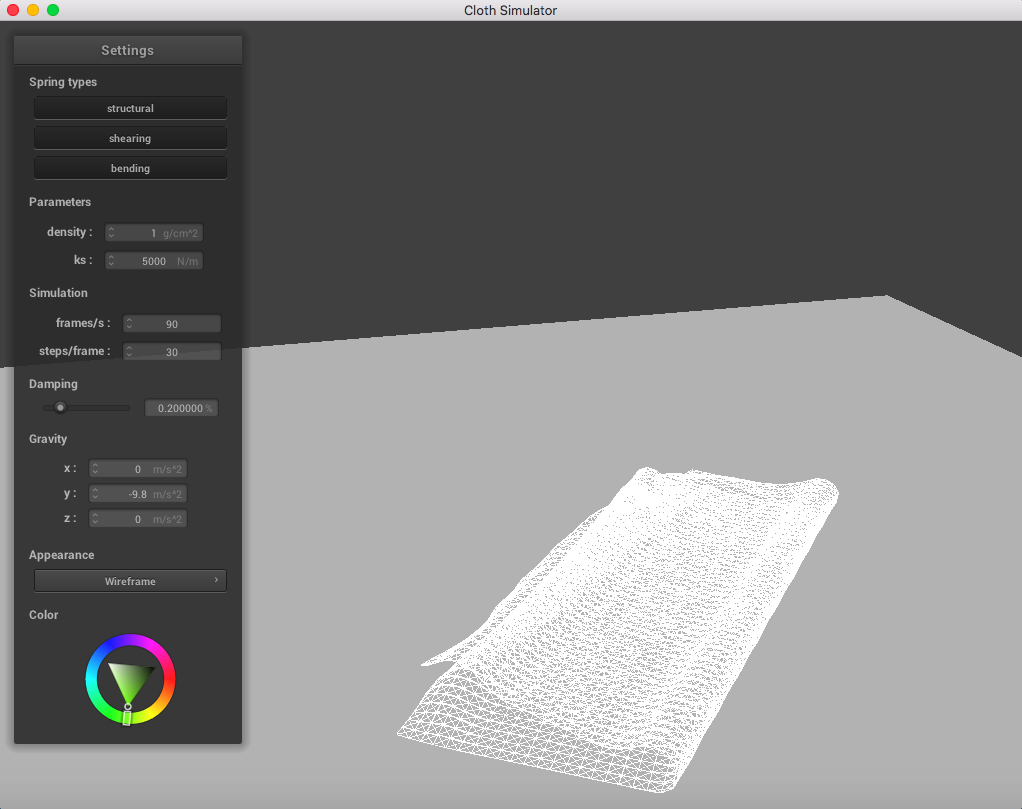

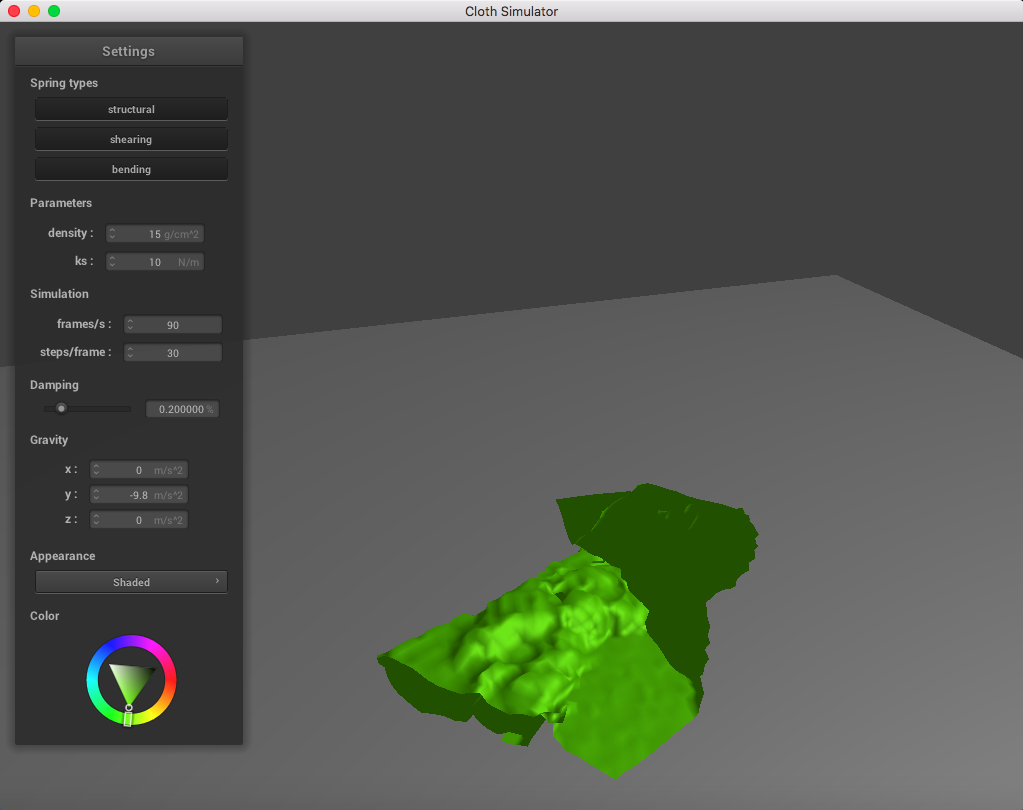

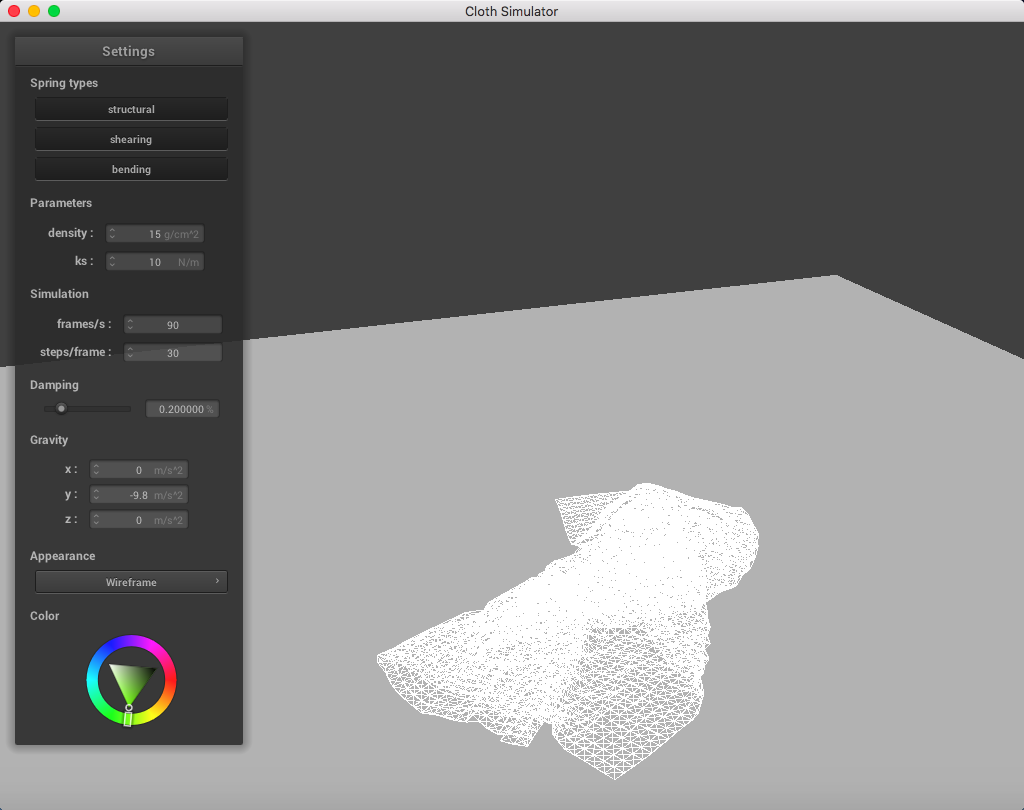

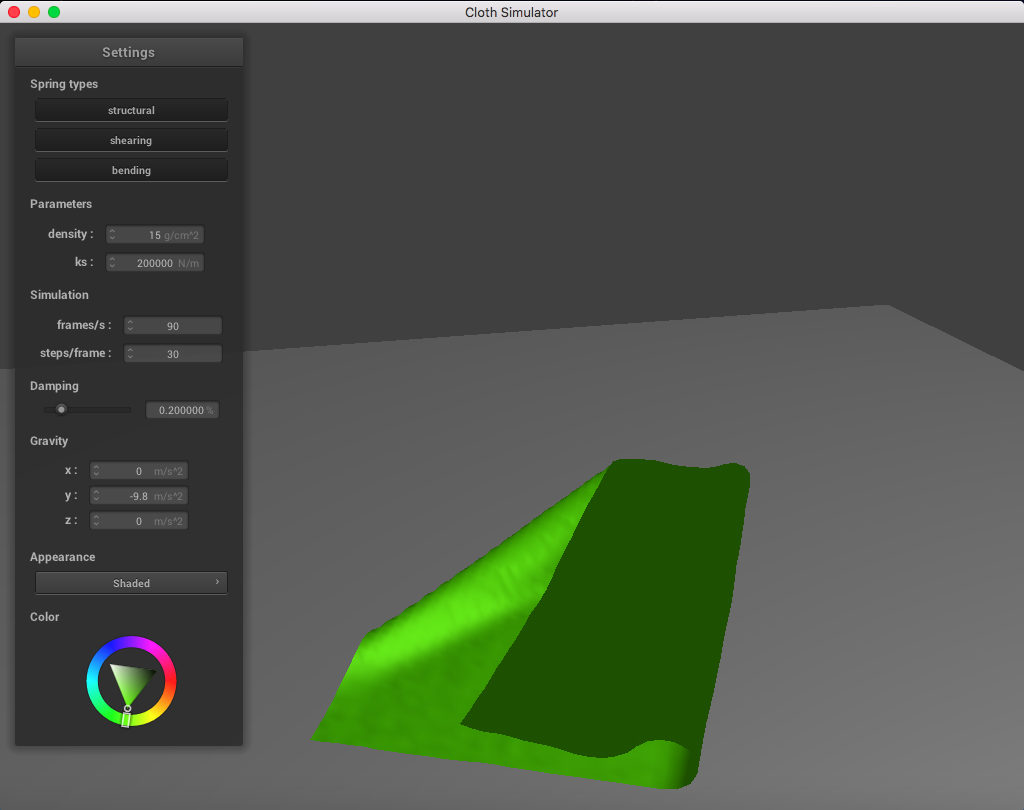

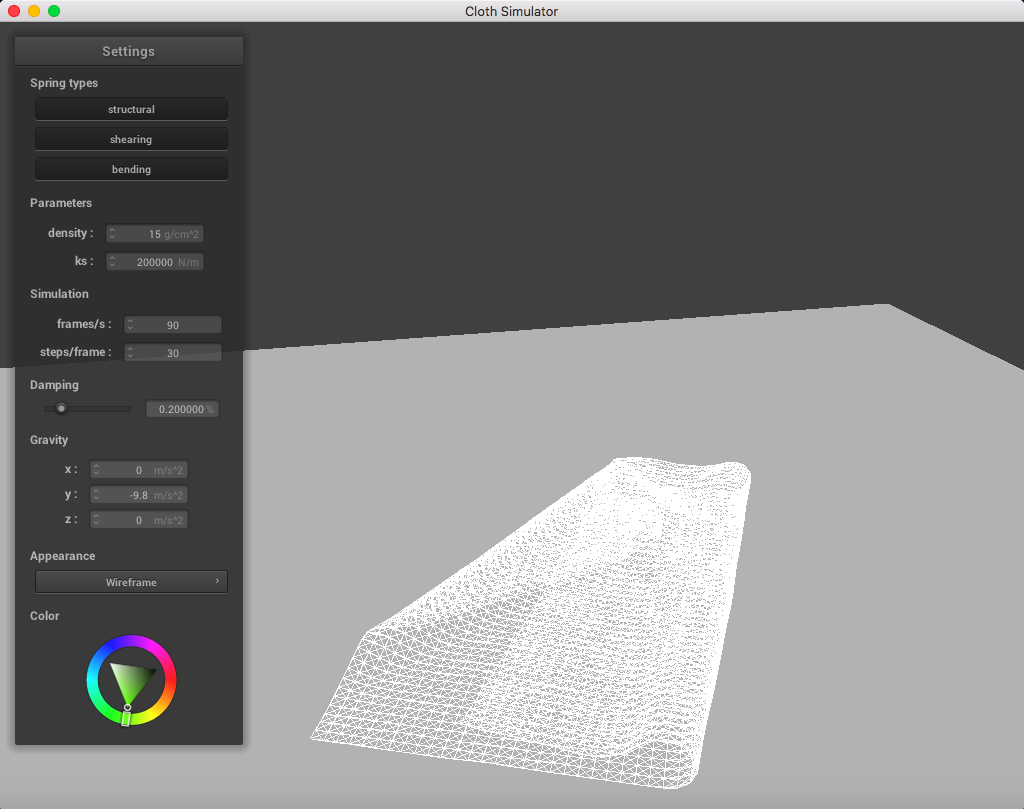

Below is a set of pictures representing a cloth simulation with self-collisions applied with standard parameters (density = 15 g/cm^2, ks = 5,000 N/m, damping = 0.2%):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

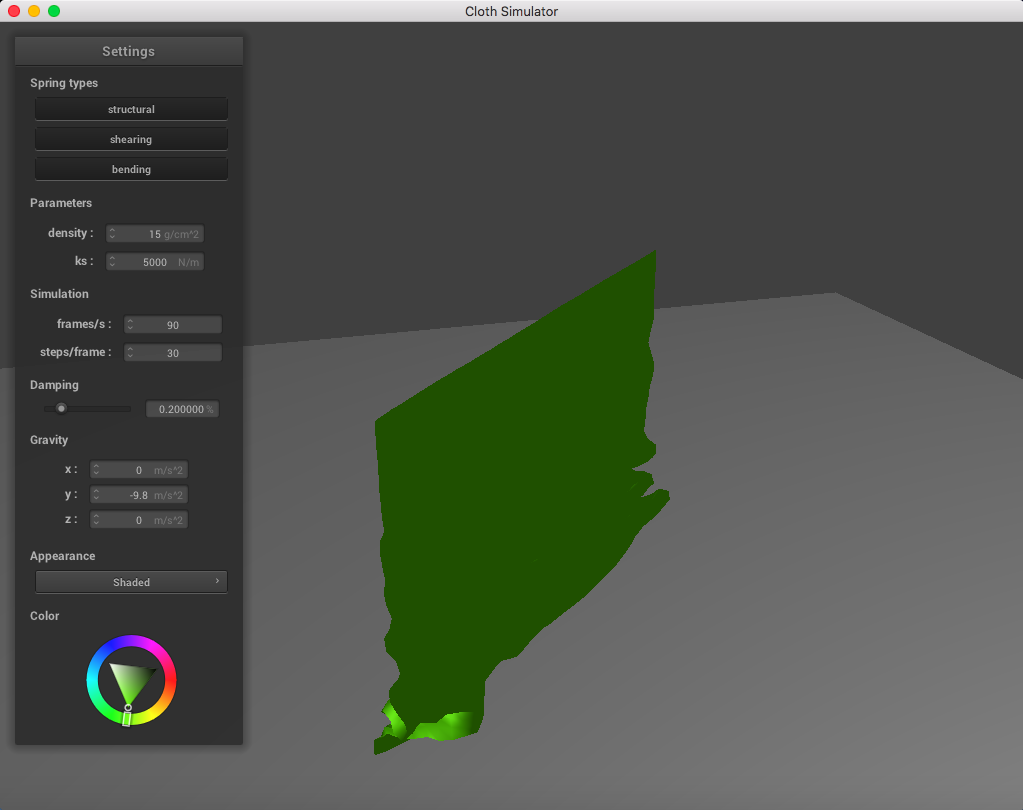

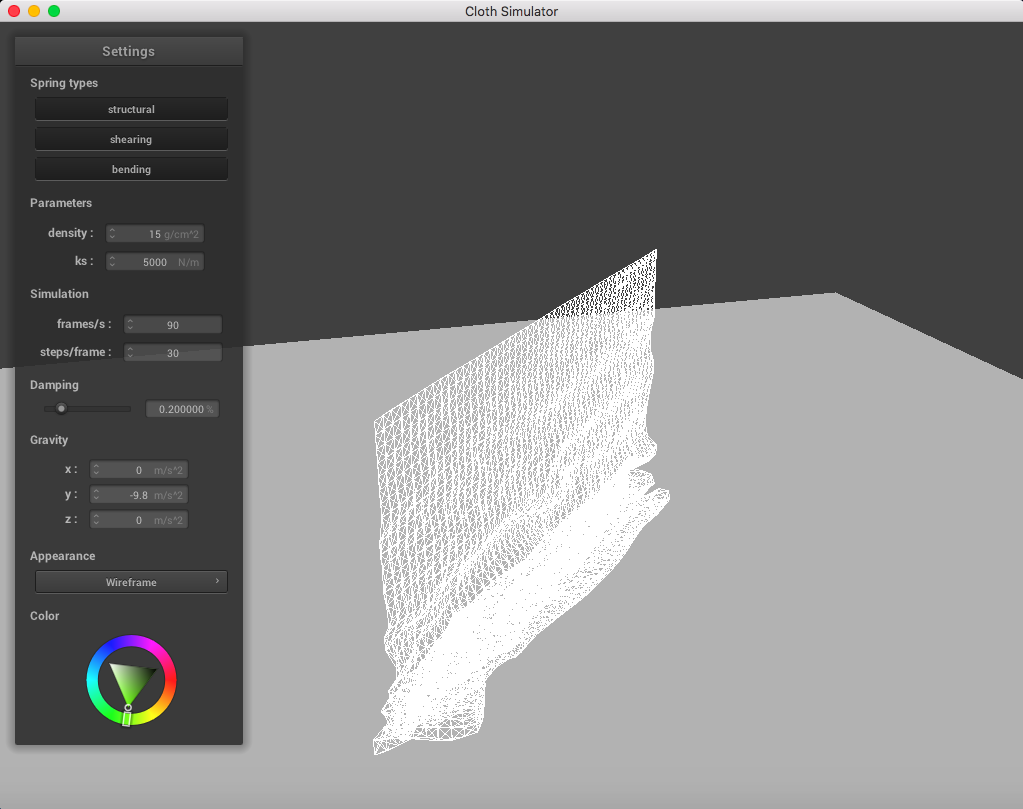

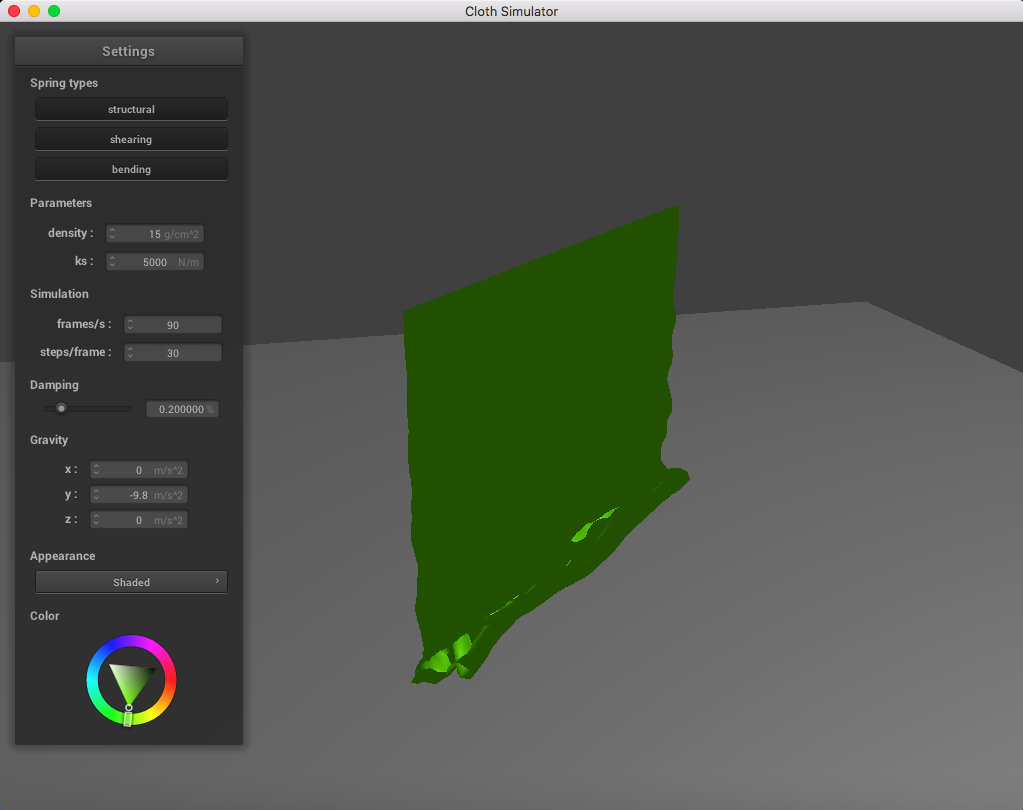

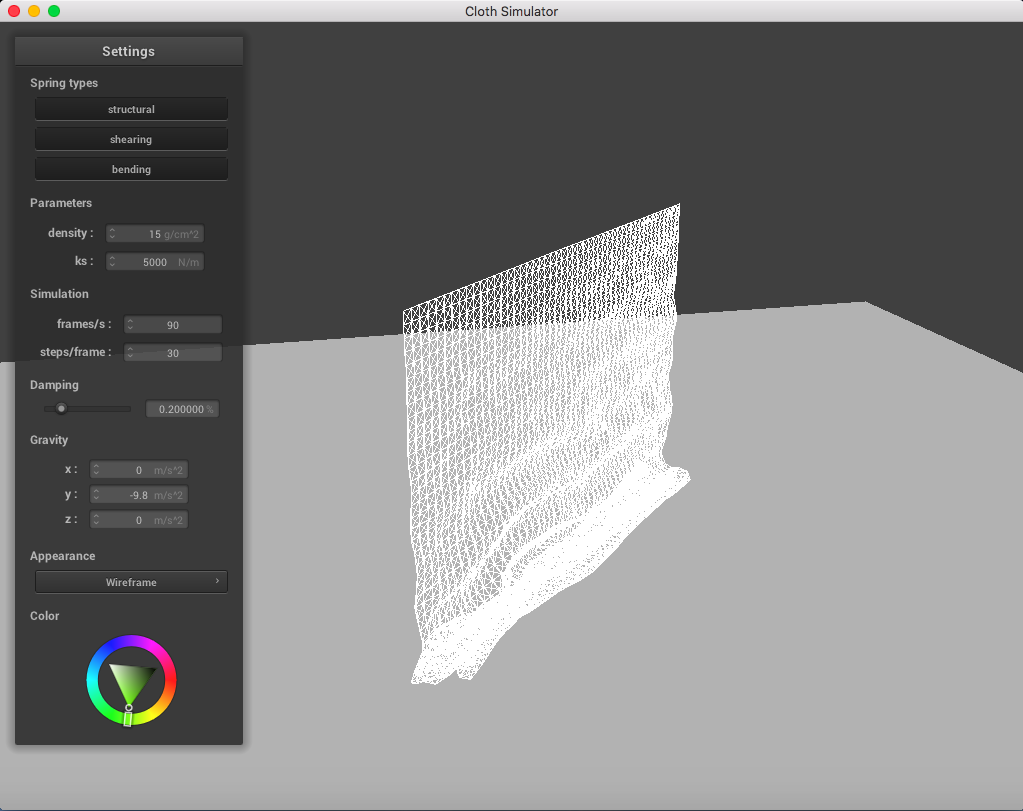

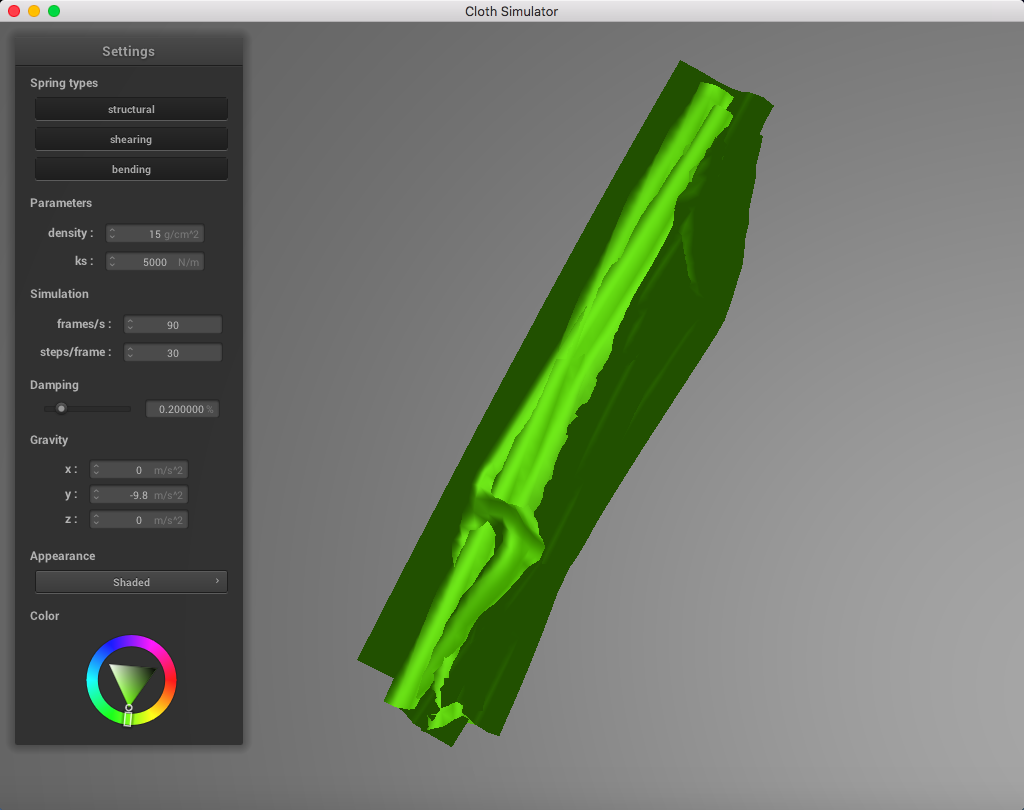

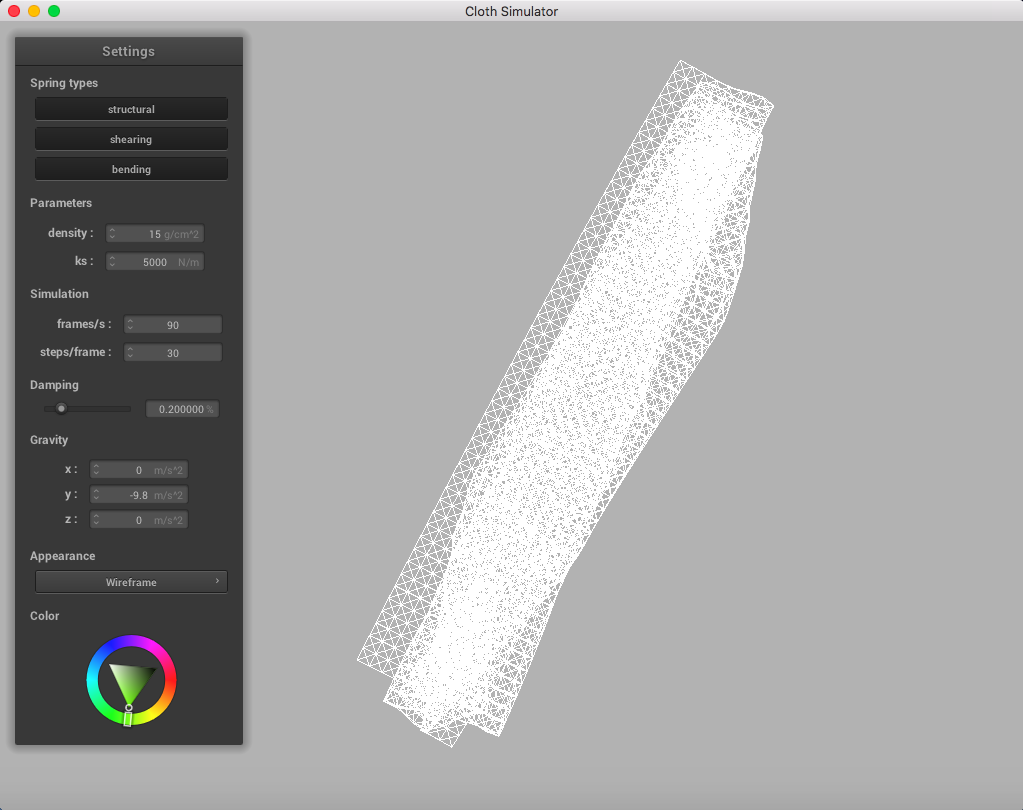

For reference, this is a simulation without handling self-collisions:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Everything is mushed together. Ugly!

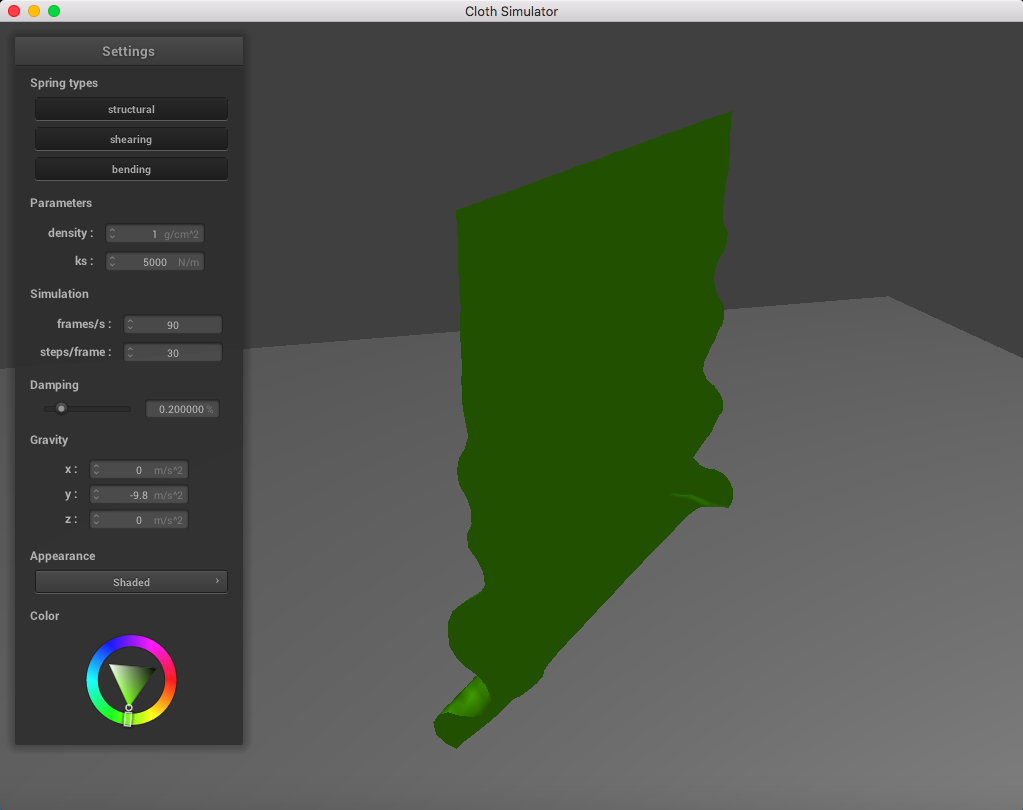

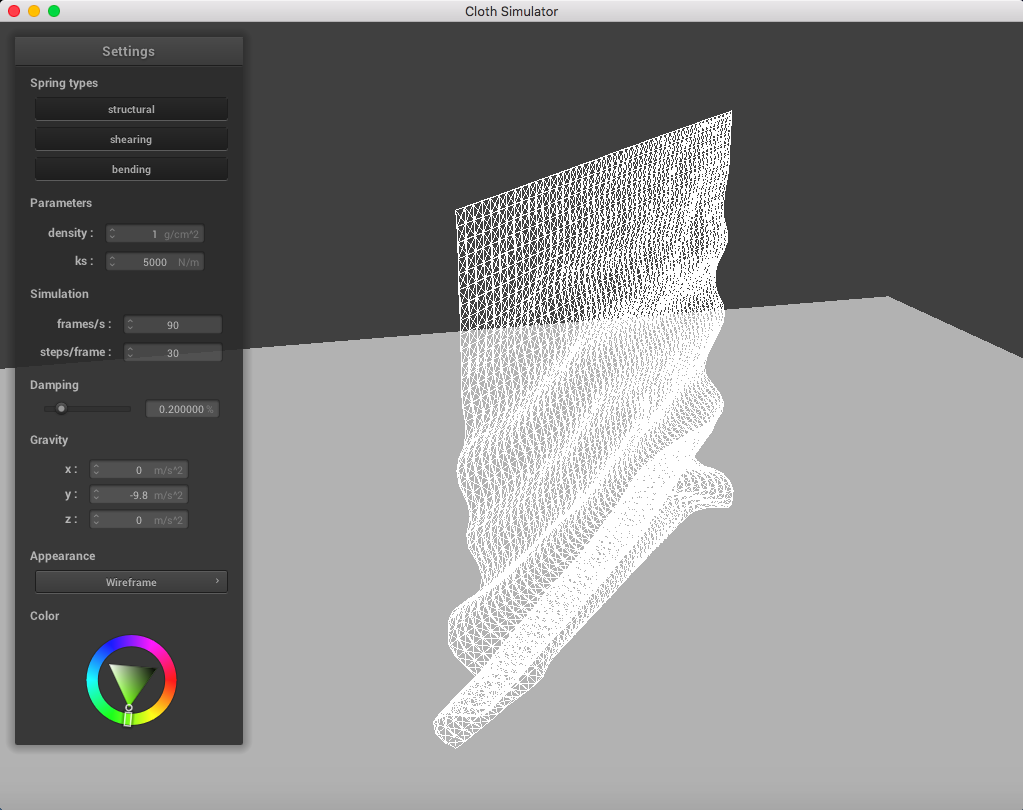

When altering the density, it was clear that a lighter density resembled a lighter cloth. It appears as though each point mass is very light and falls down smoothly when having a low density, in contrast to a higher density.

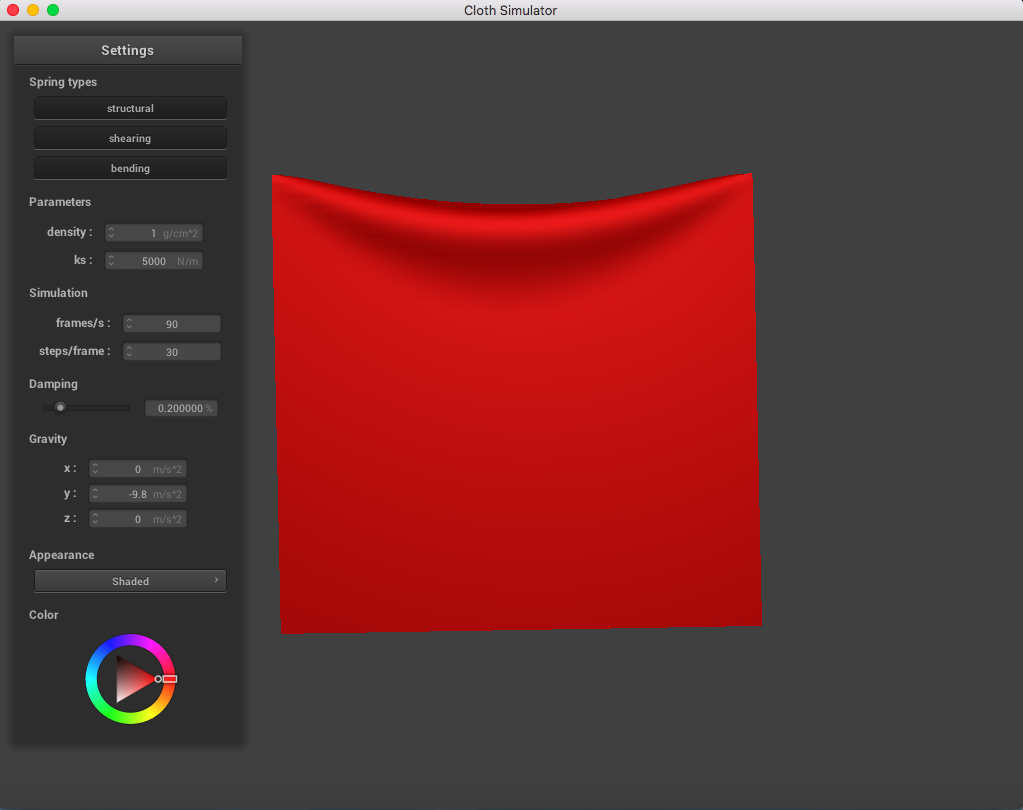

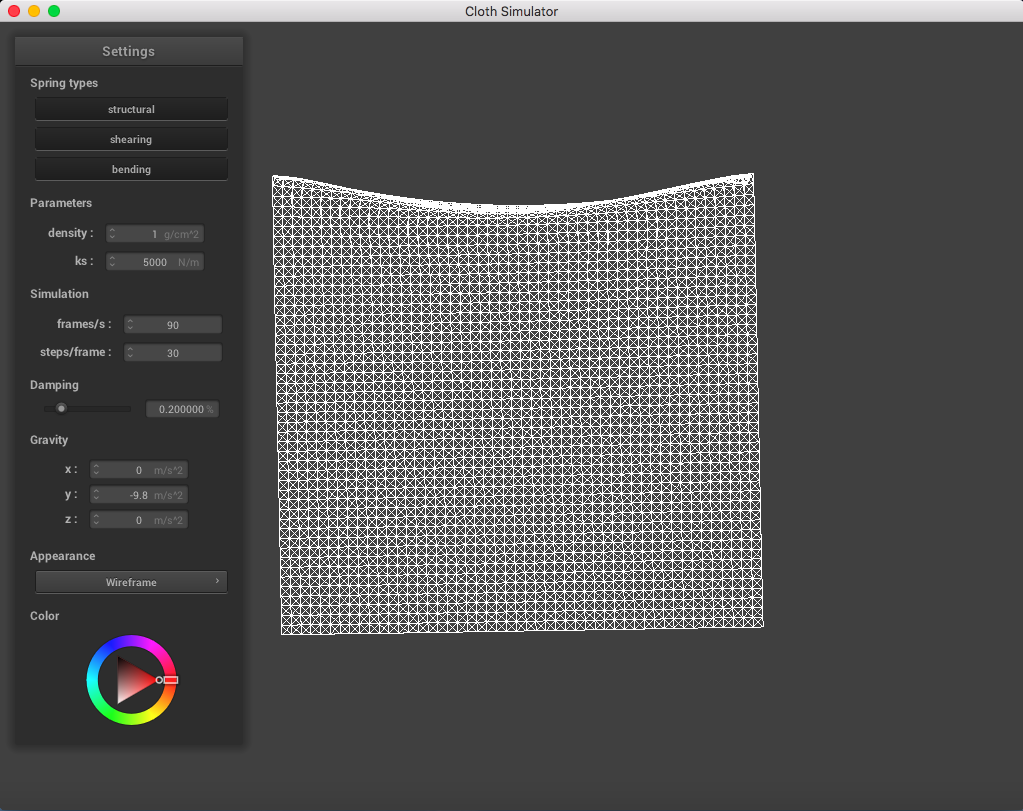

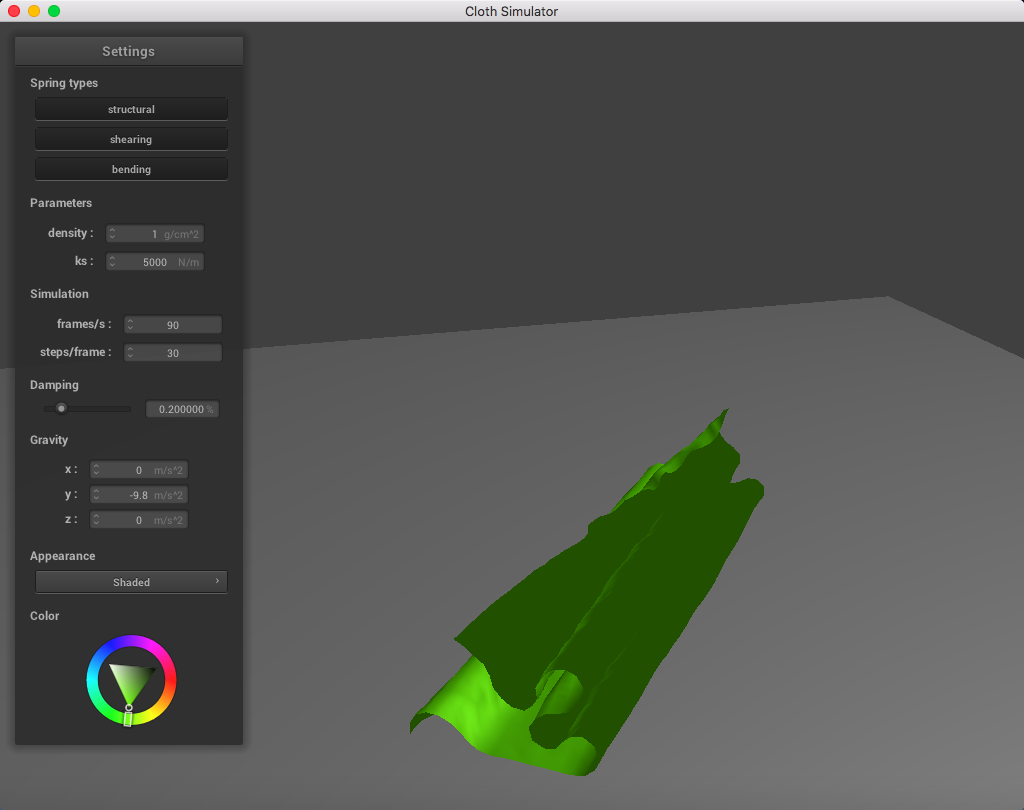

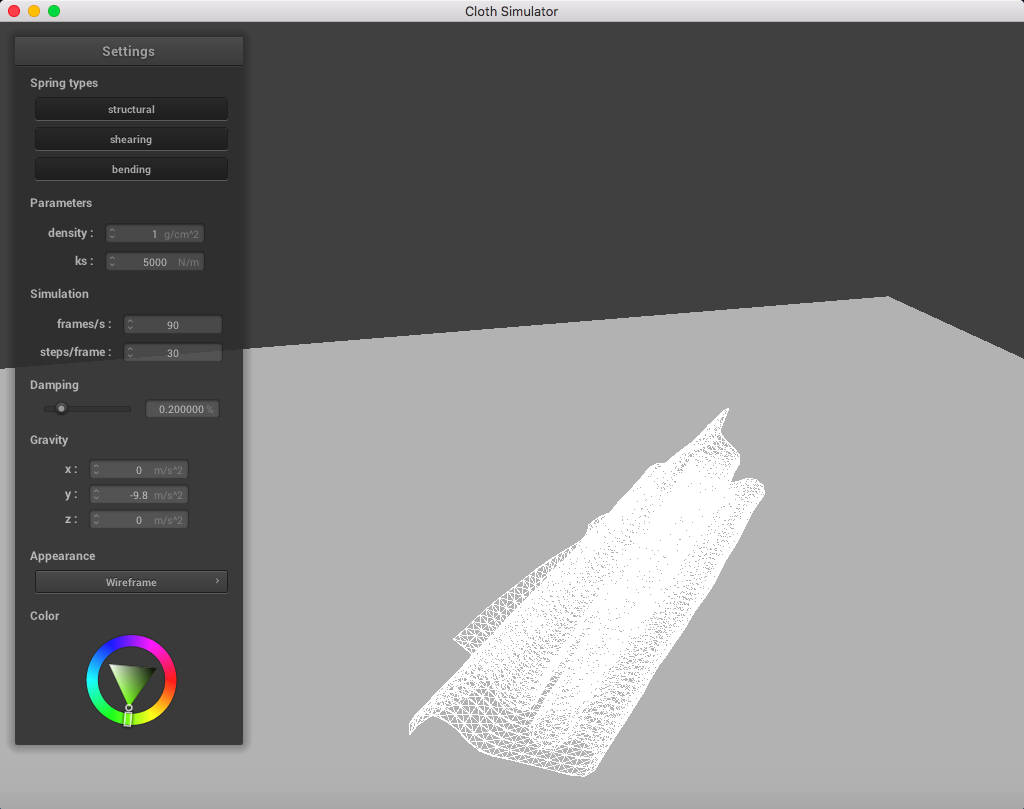

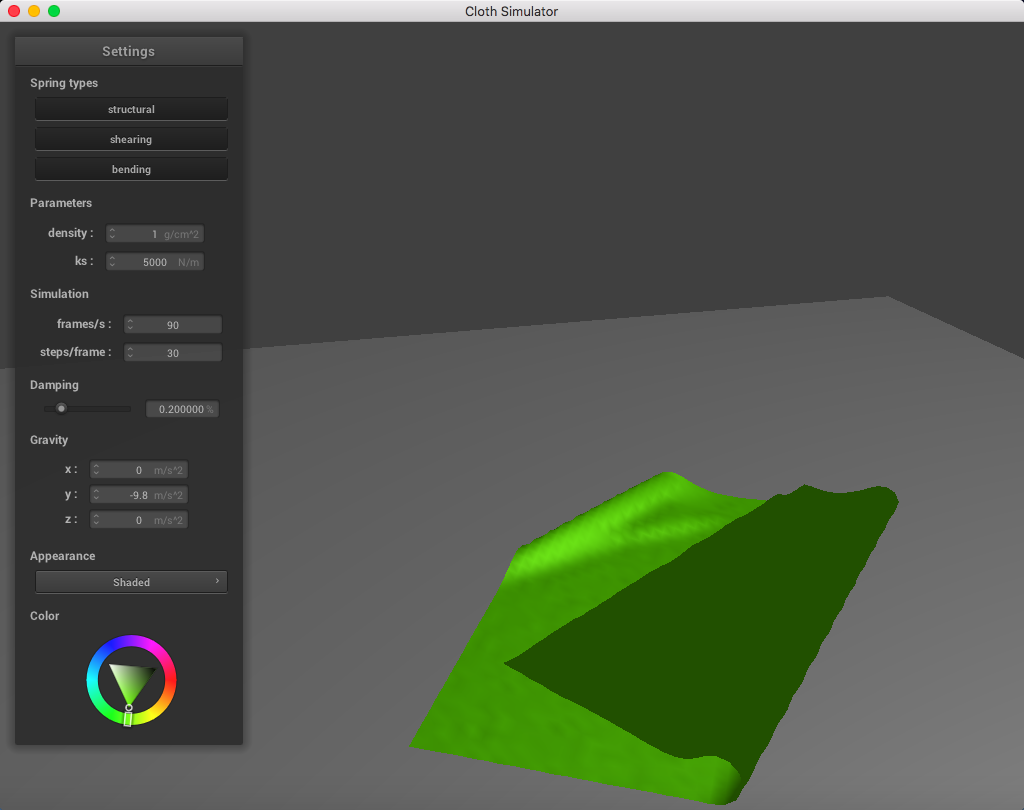

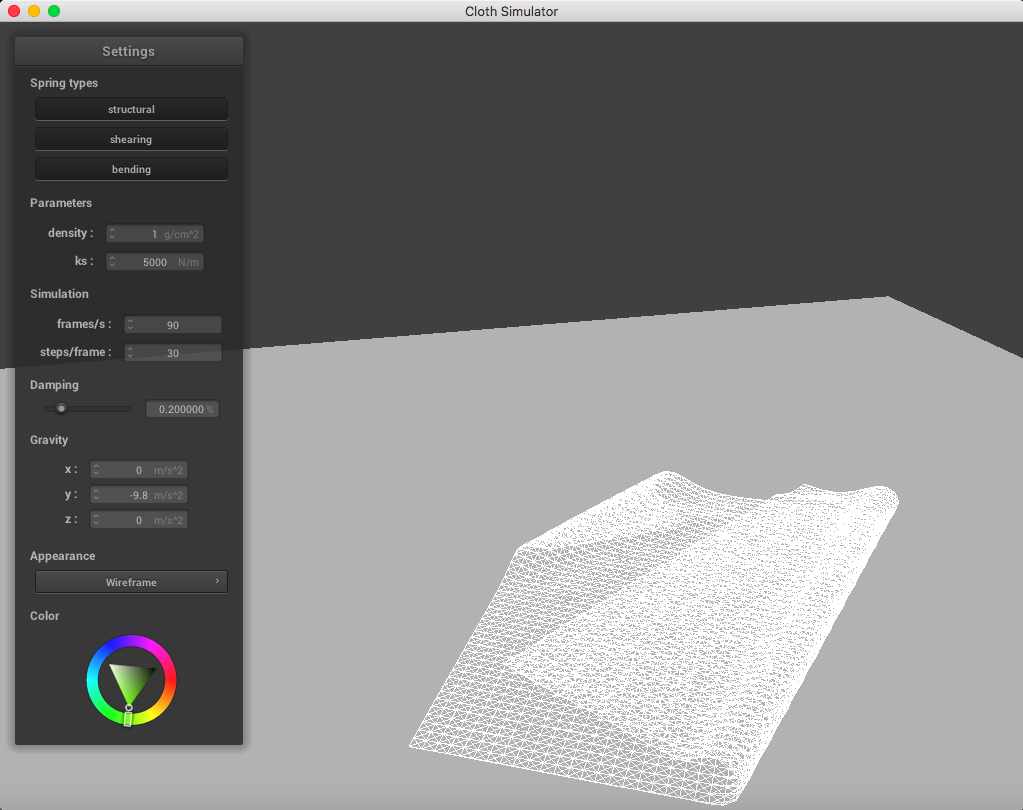

Here is a cloth at density = 1 g/cm^2:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

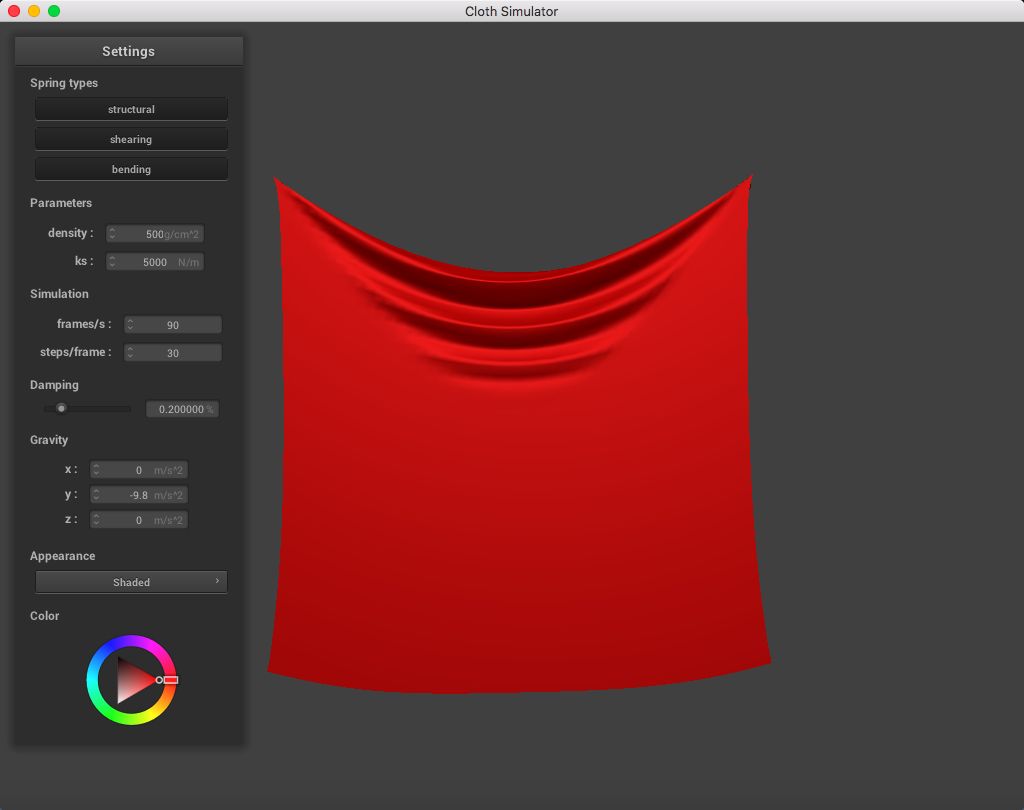

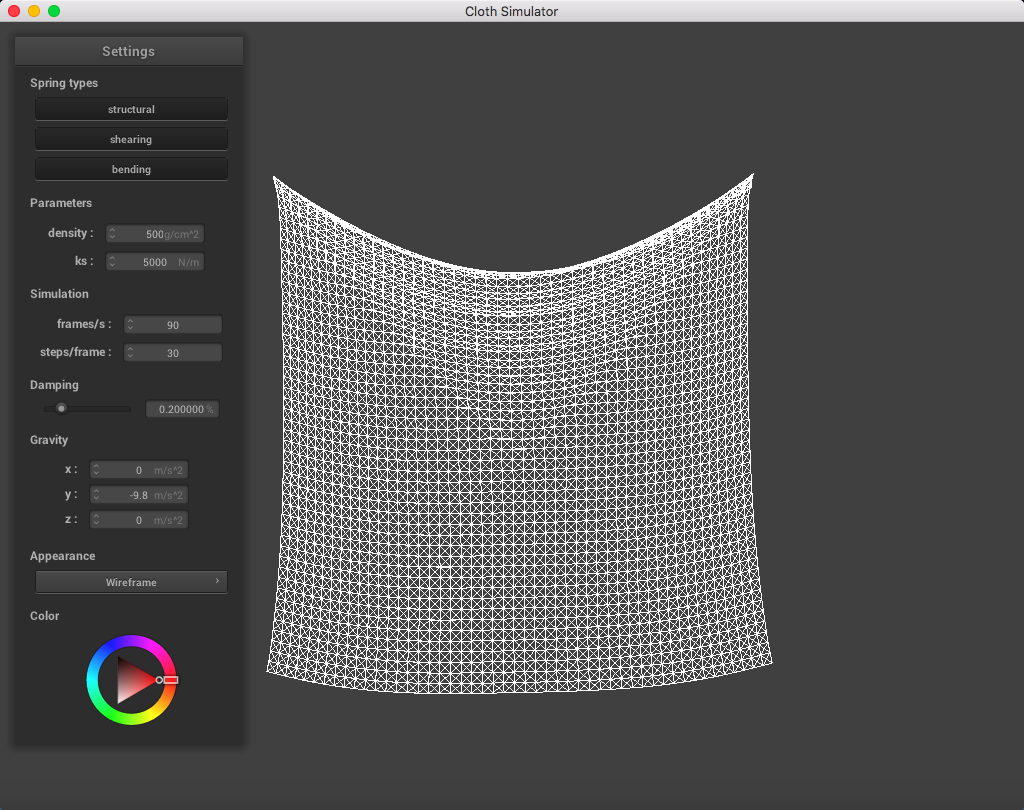

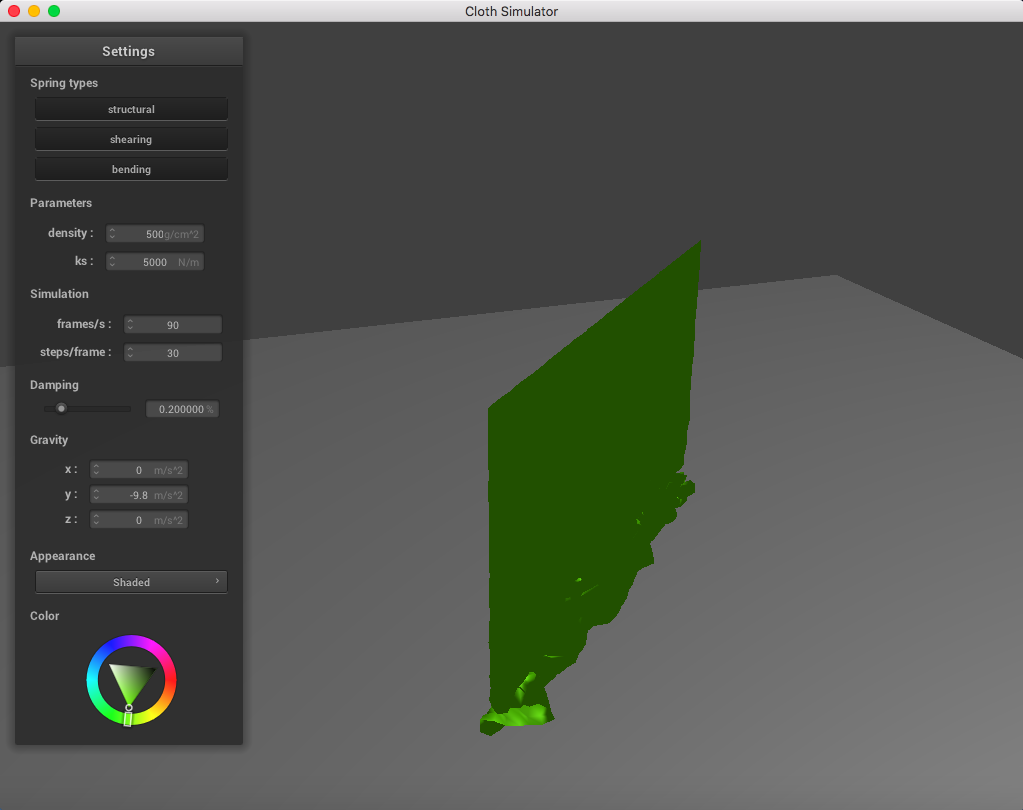

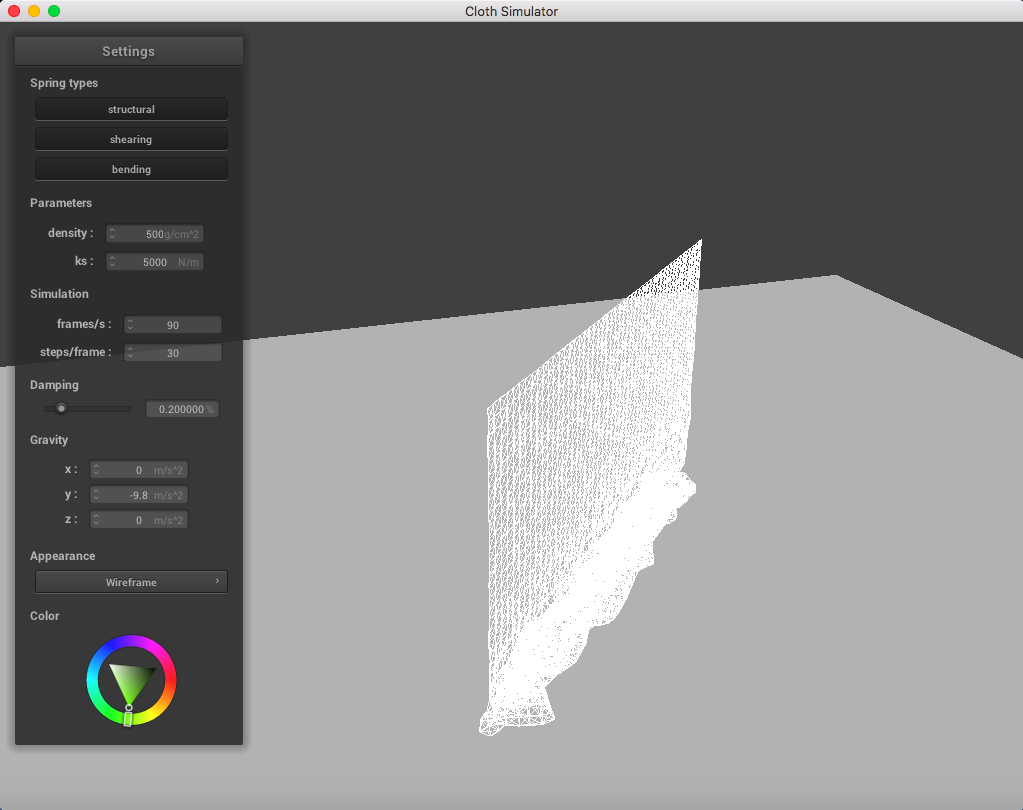

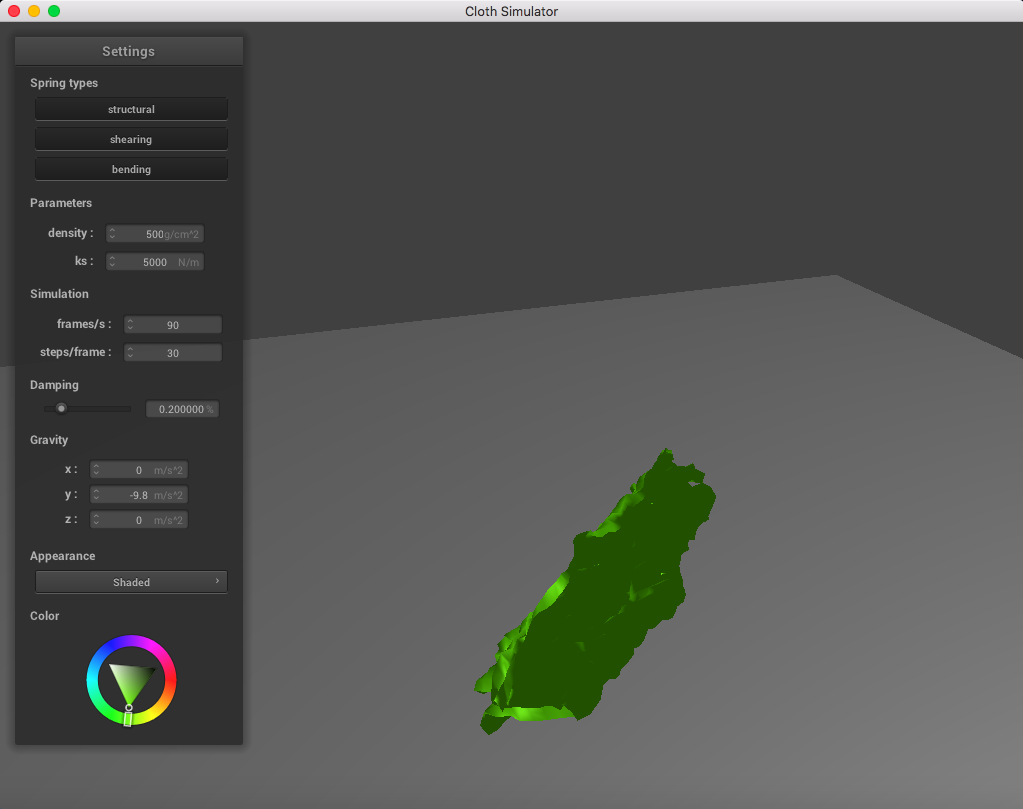

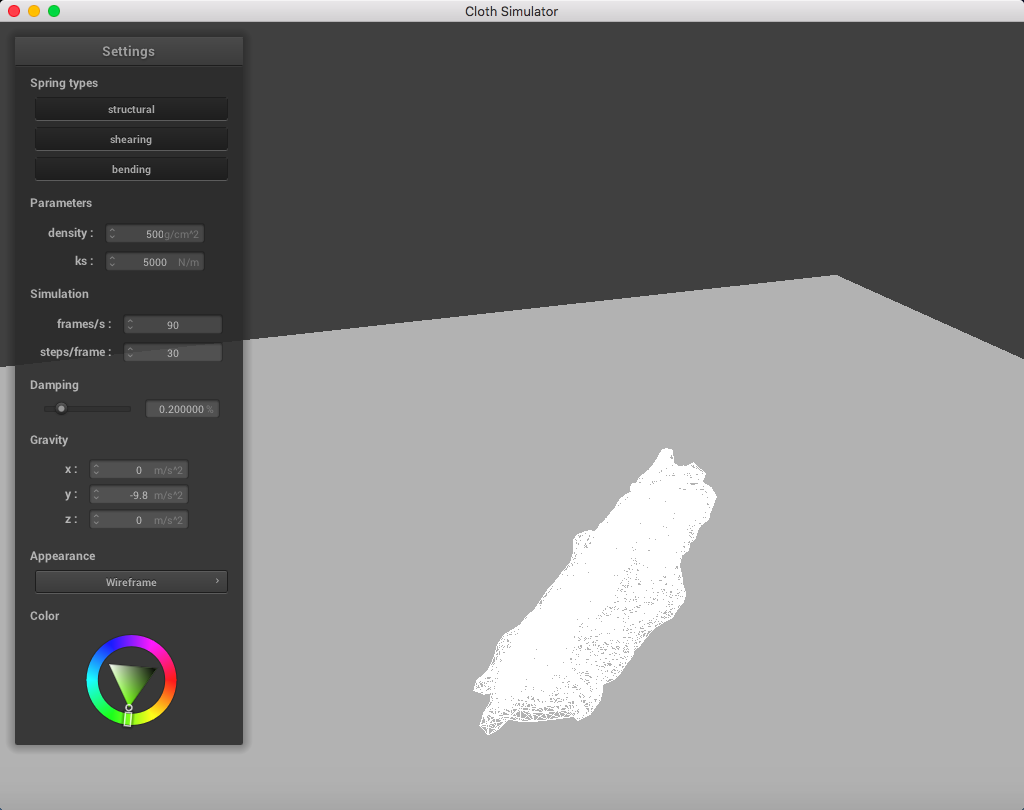

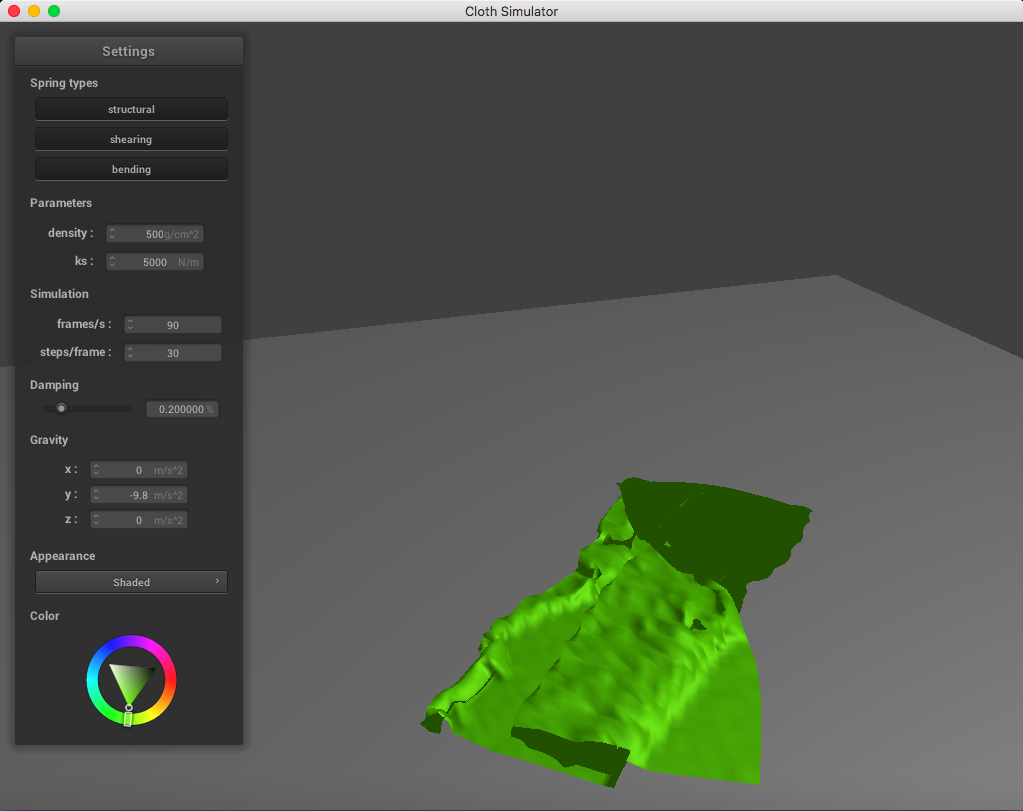

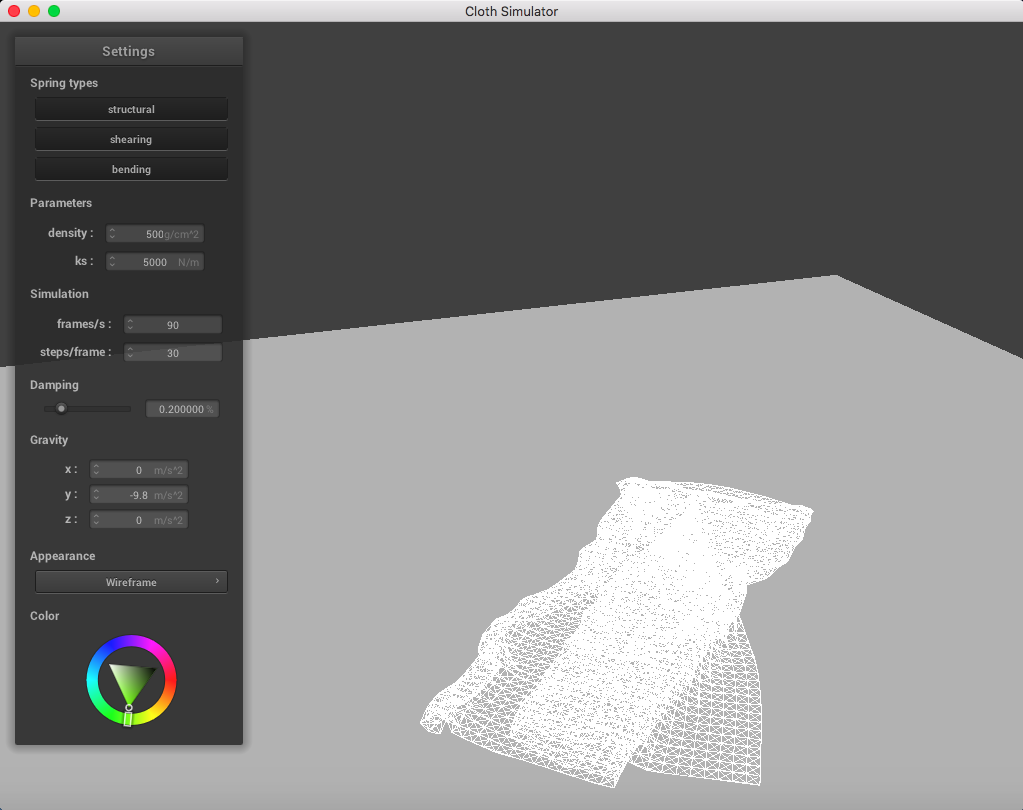

Here is a cloth at density = 500 g/cm^2; you can notice a significant change in weight of the point masses:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The results of varying ks are nearly the same as the inverse of varying the density. In this case, a lower spring constant ks resulted in a cloth that appeared heavier, and this comes from the fact that we have a weaker spring constant for the springs between each point mass.

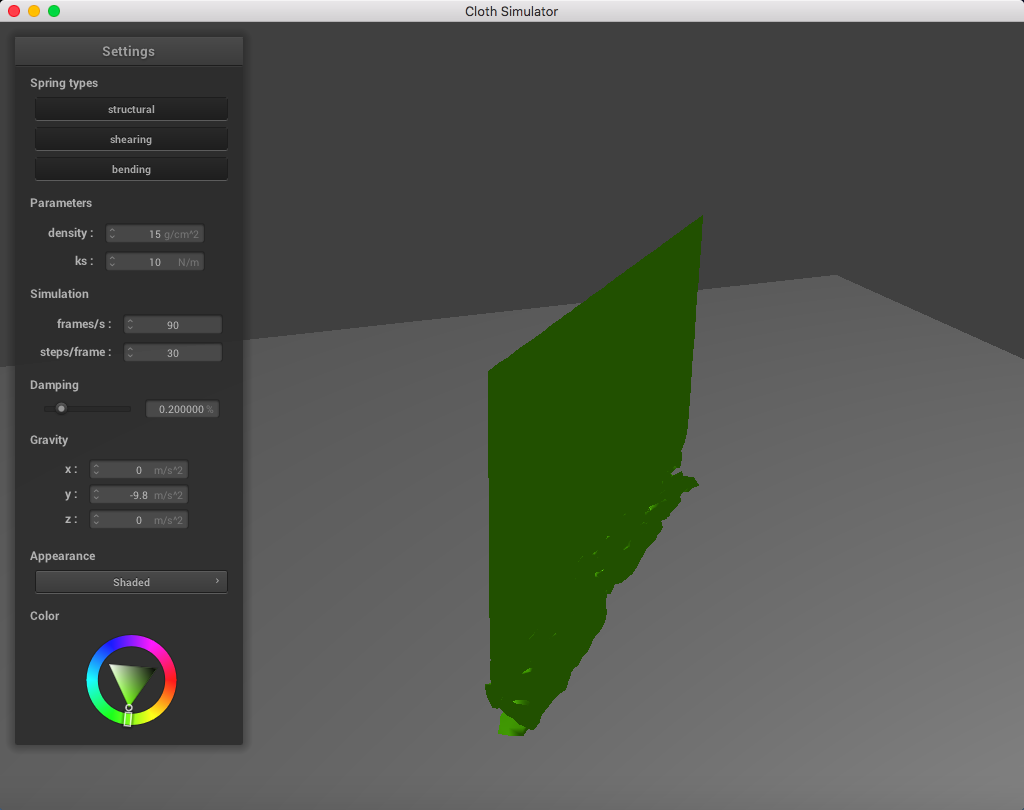

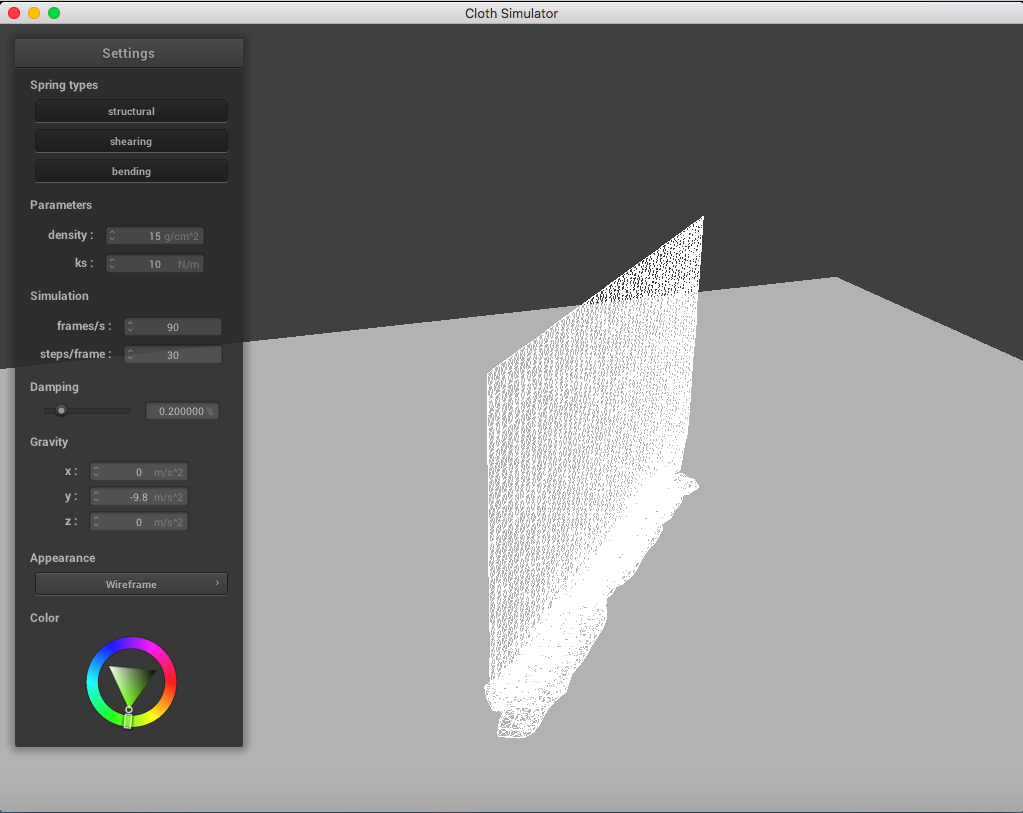

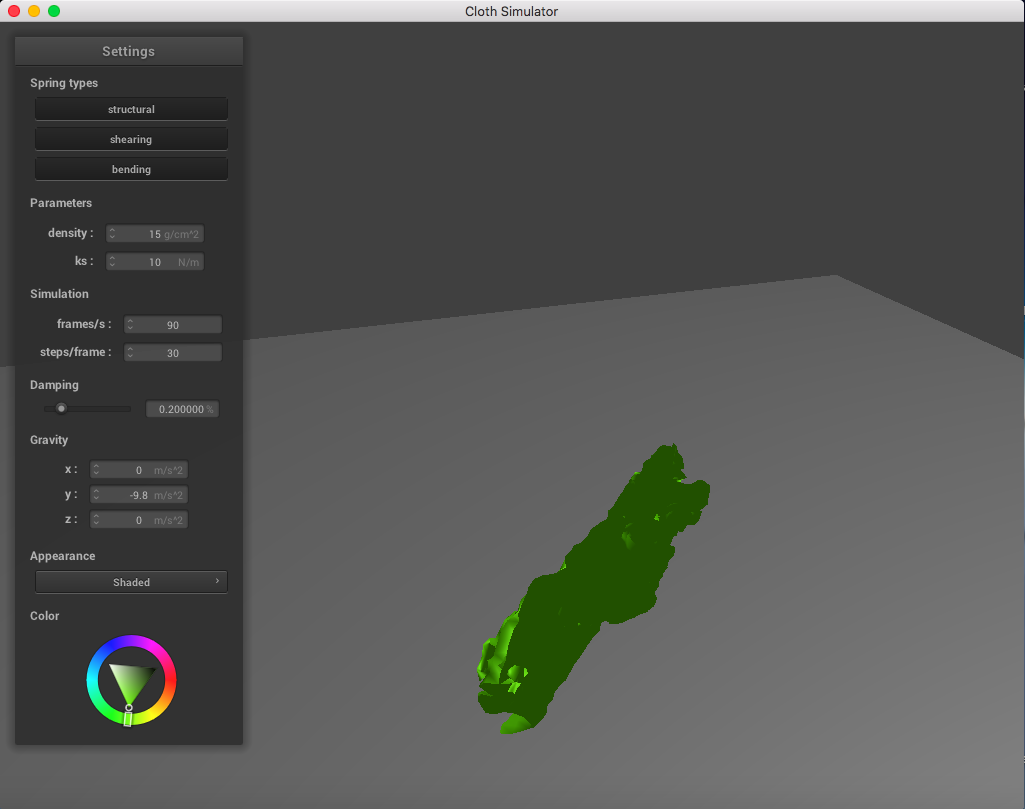

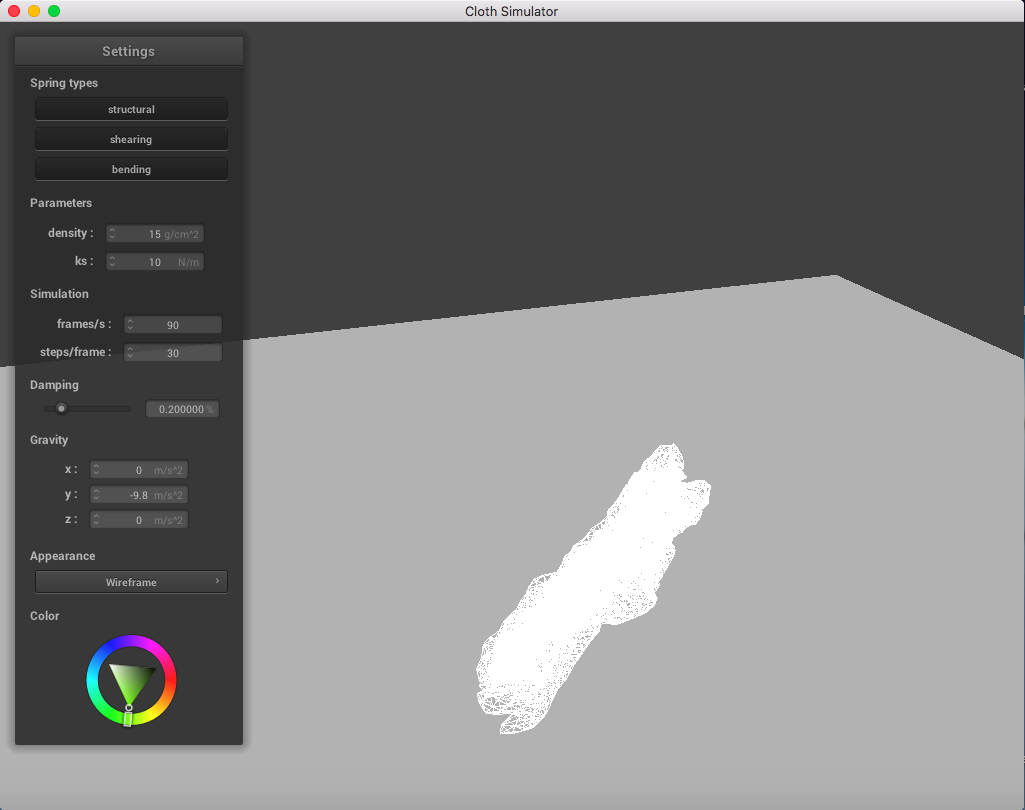

Here is a cloth at ks = 10 N/m:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

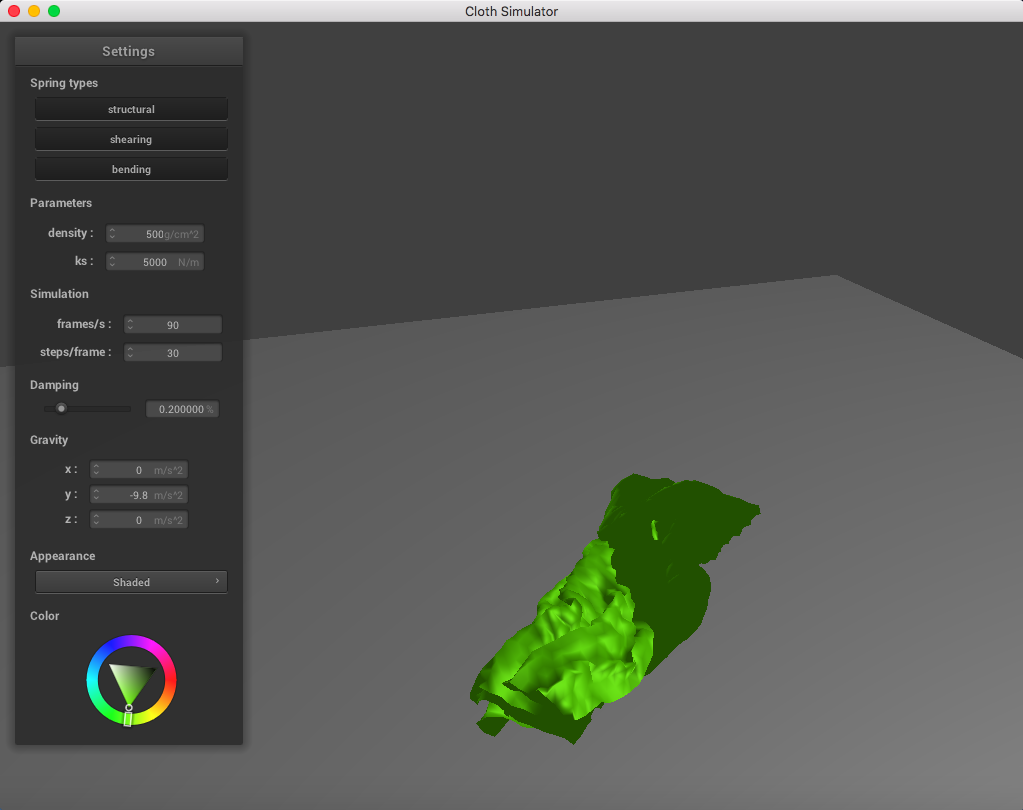

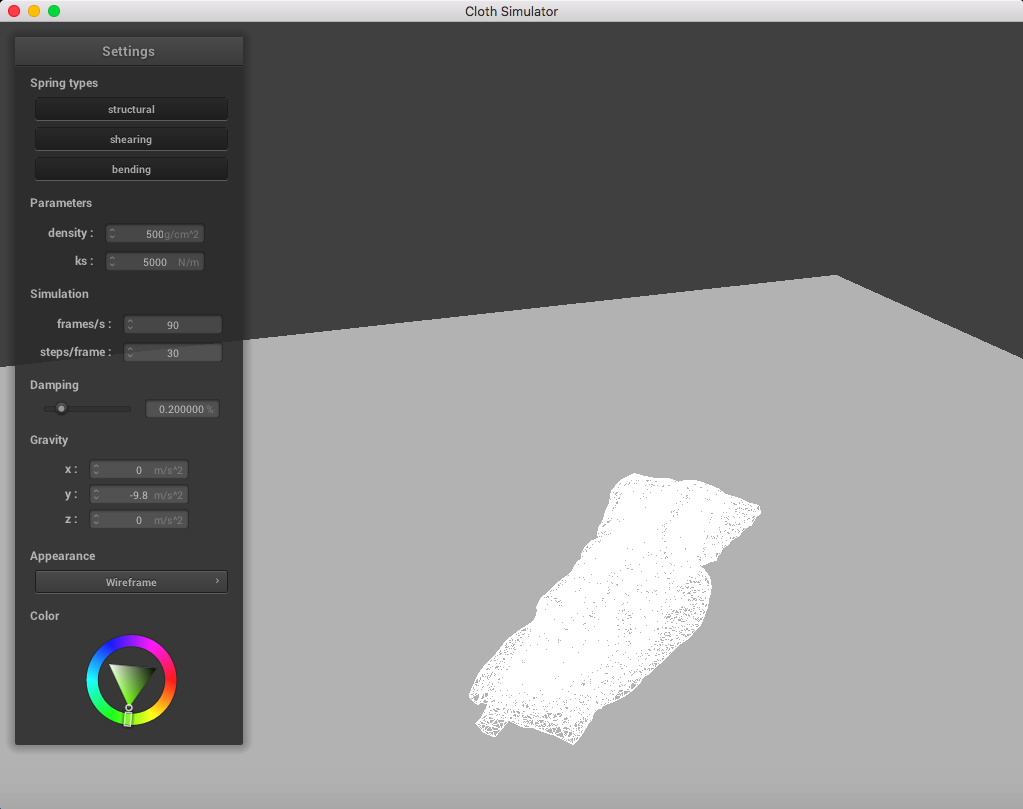

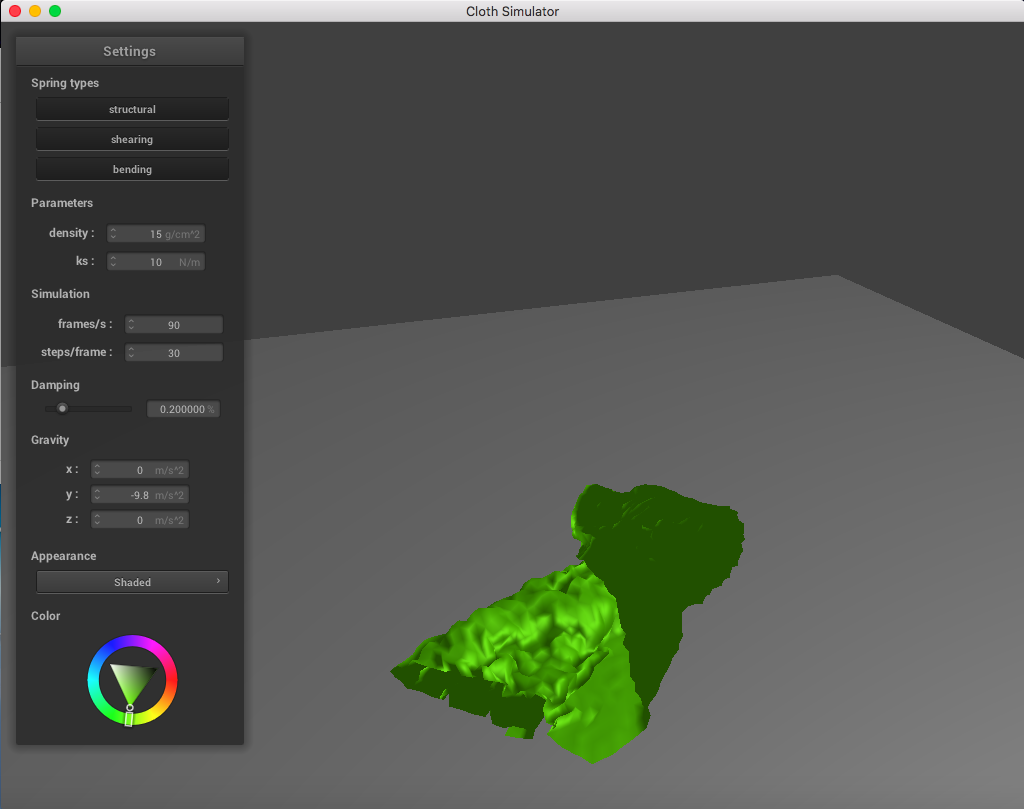

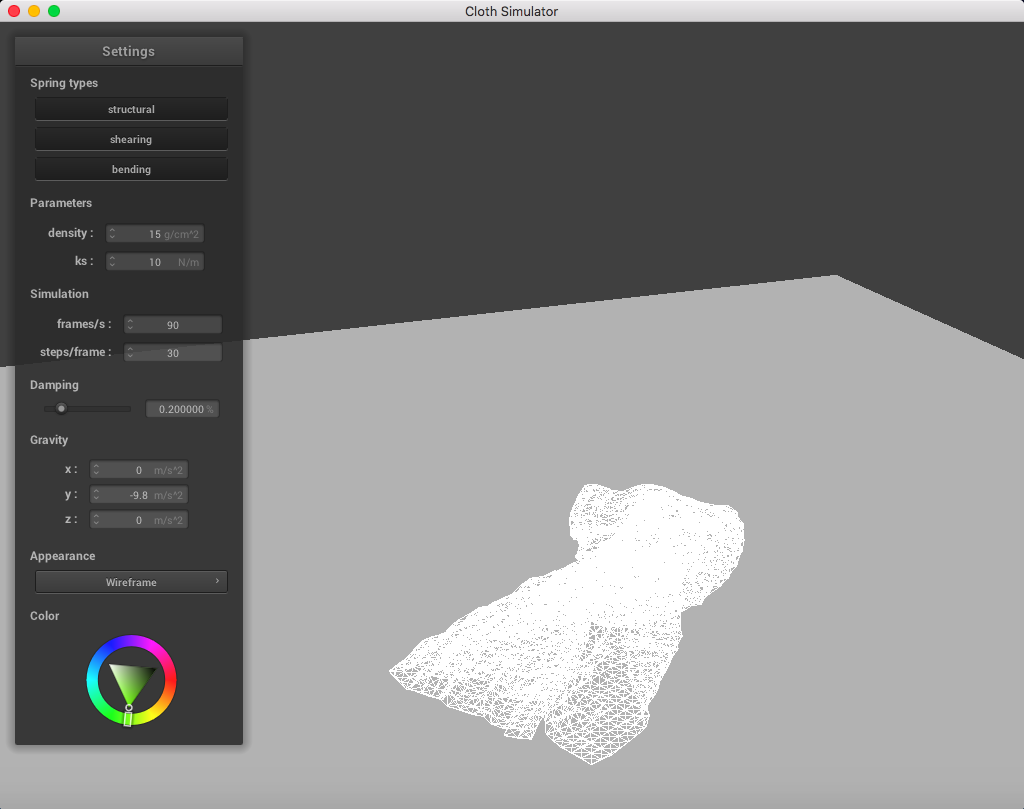

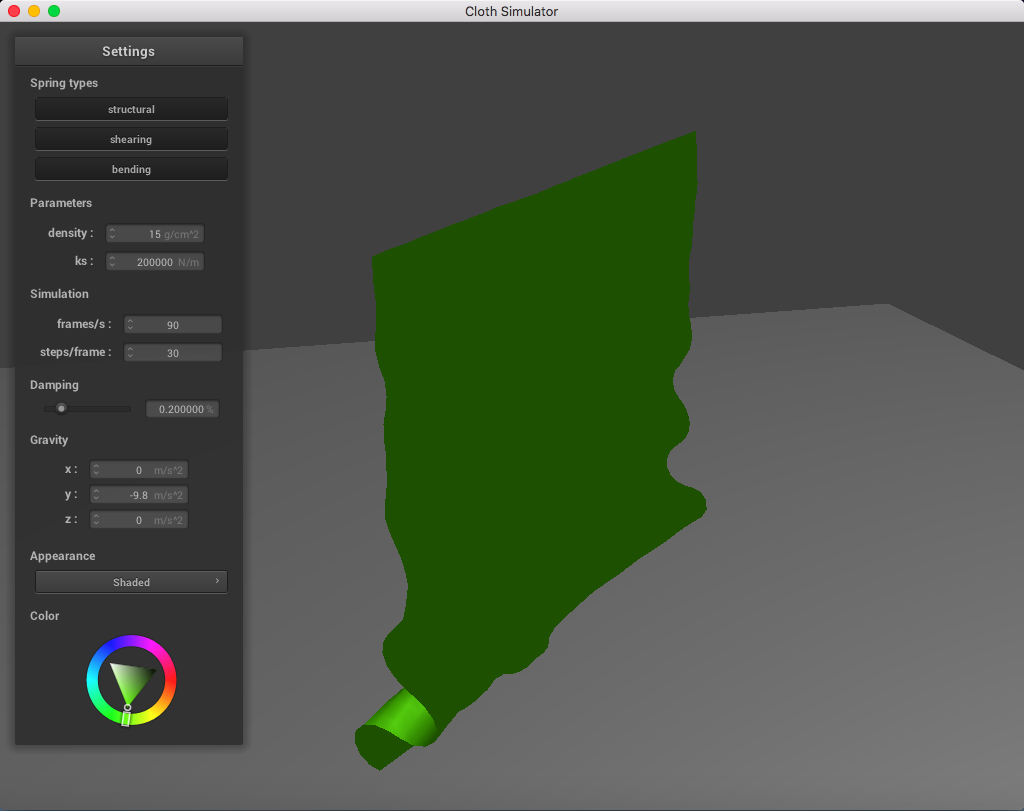

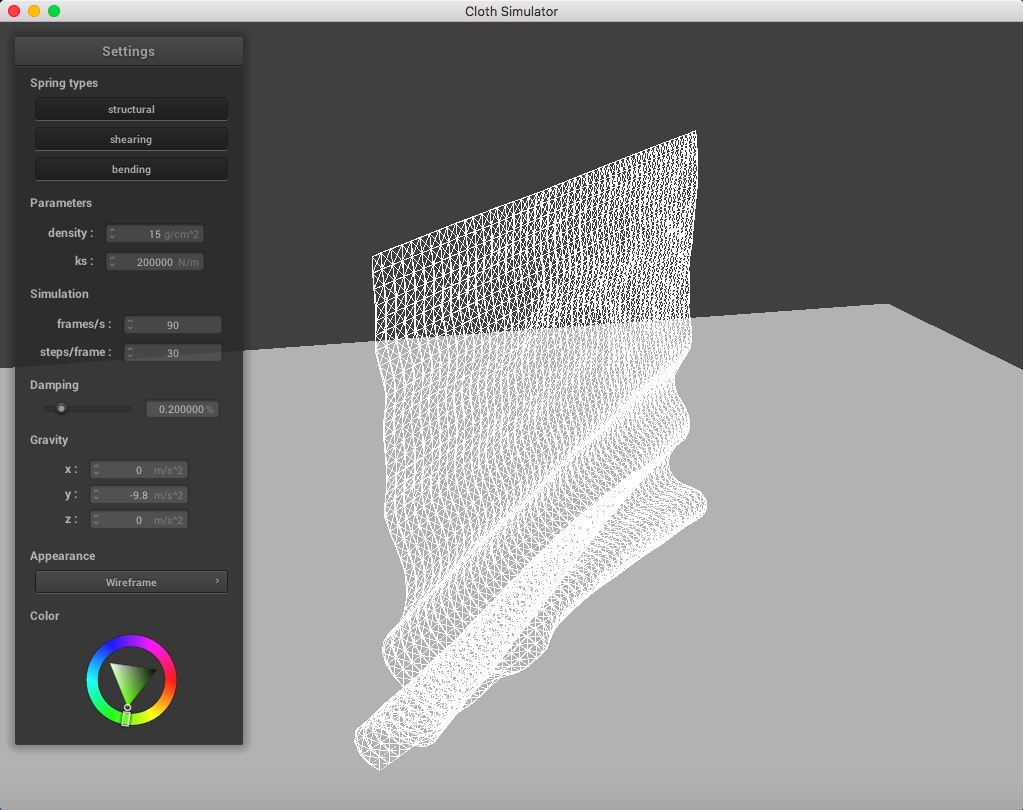

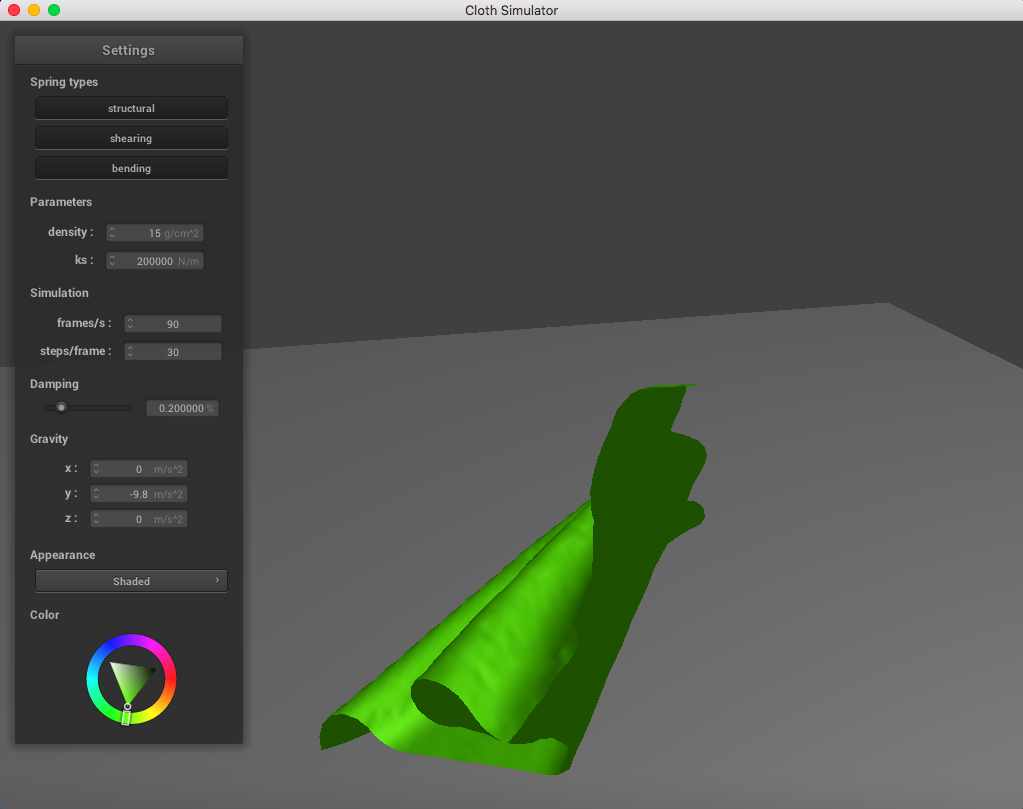

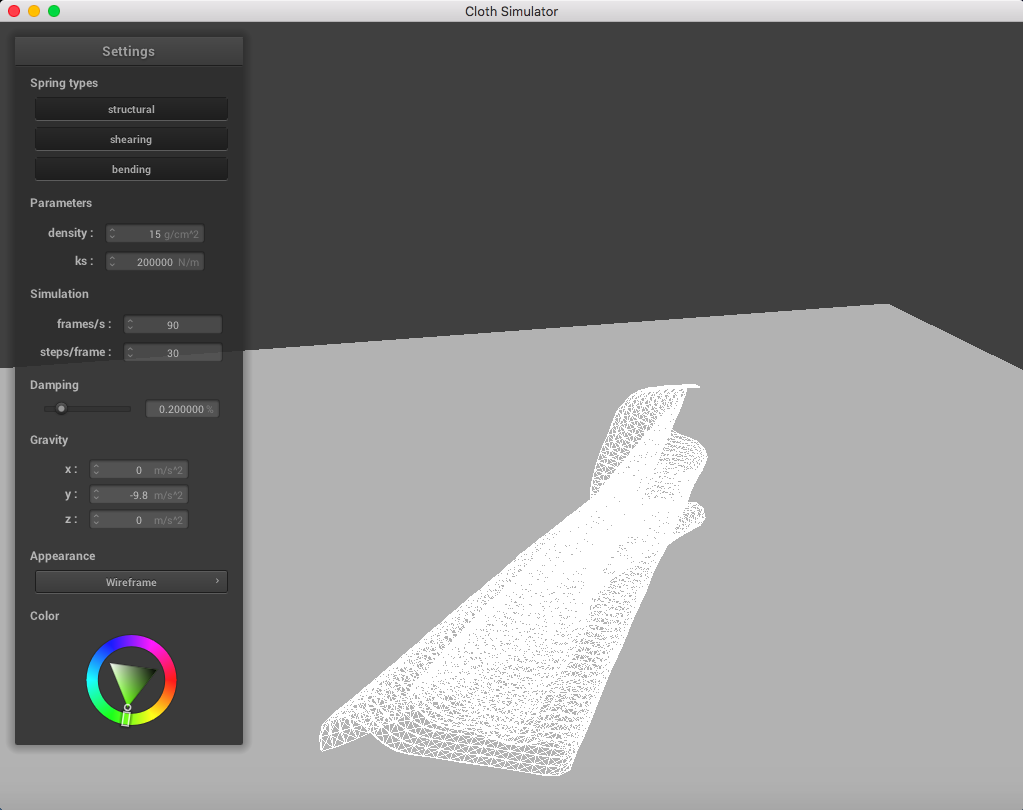

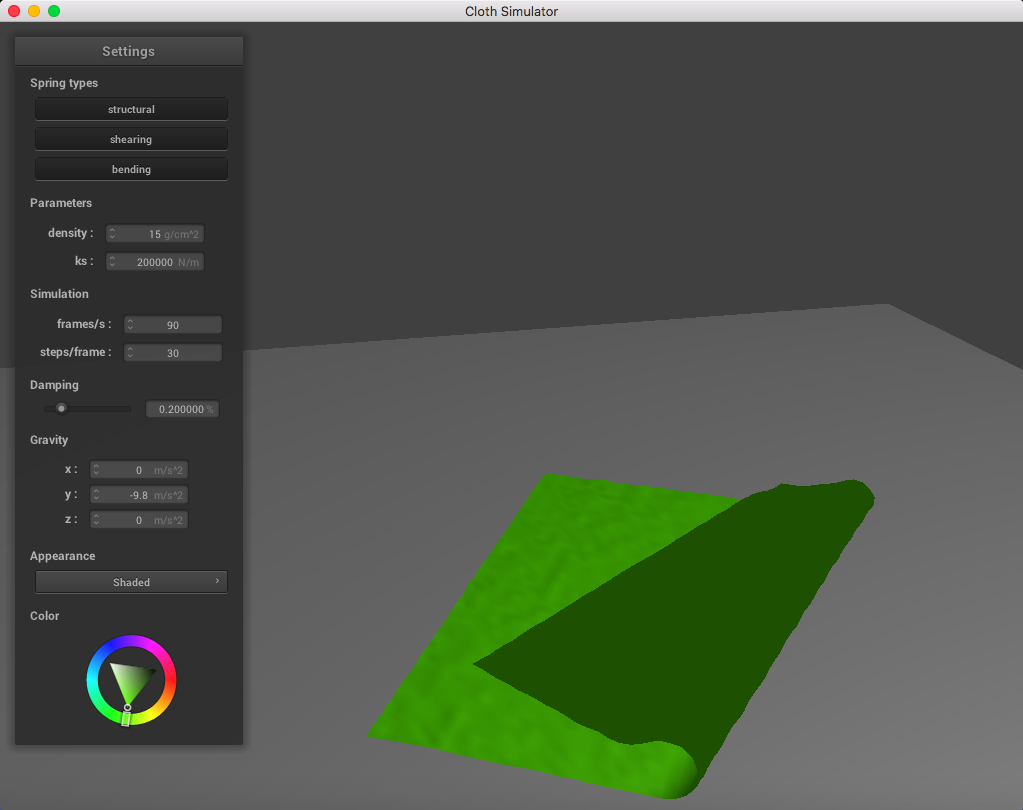

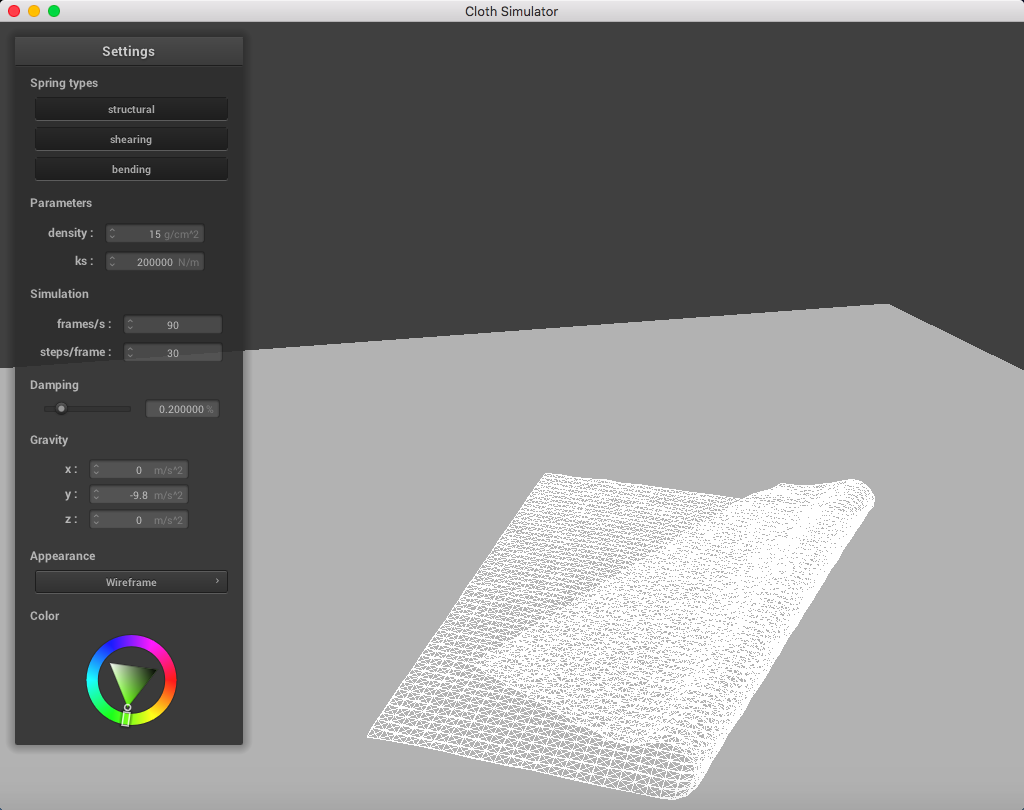

Here is a cloth at ks = 200,000 N/m; the point masses are are much more continuous and do not fold abruptly as much:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|